King Crimson is completely over. For ever and ever.

Robert fripp, 1974

One of the first bands we championed — back when the magazine was still called the Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press — was King Crimson. I had a friend from engineering school who was a huge fan and, like the rest of us, eager to proselytize in print. He wrote an article on his favorite band for our first issue and returned to his subject as often as we would let him.

Fanzines in those days, like the webzines of today, were treated surprisingly well by the publicity departments of some labels because of their willingness to enthusiastically cover intriguing artists mainstream outlets were happy to ignore. And press was still thought to have an influence on record sales. So, despite our tiny circulation, amateur production values and monumental inexperience, we were able to arrange an interview with Robert Fripp, a figure of great fascination in the British music press for his prim, buttoned-down demeanor, instrumental exactitude and heady, didactic pronouncements. He was an intimidating intellectual figure and a monumentally original trailblazer. One of a kind.

If you’re not familiar, watch one of the wonderful weekly pandemic videos the 74-year-old guitarist and his wife, the actress and singer Toyah Willcox, have been posting, for an inkling of just how odd a rock star he really is. And he was barely 30 and not even seven years into his singular career at the time of this encounter.

Lou Reed had Lester Bangs to joust with; in our little world, Robert Fripp had a large, shy electric engineer named Ihor Slabicky. This interview, which ran in three issues of Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press (six through eight, 1974 – ’75), is an amazing colloquy, the sort of unguarded, knowledgeable back and forth — a display of mutual respect and curiosity — you don’t see much of in music journalism any more. (The original headline was: “Who’s Asking the Questions Here?”)

The fact that he was, at the time, announcing the dissolution of a band that has nonetheless continued off and on for another half century is not even the most surprising thing in this amazing interview, which has been lightly edited from the original publication.

Interview by Ihor Slabicky

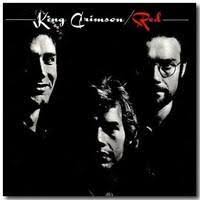

This interview was held in the New York offices of Atlantic Records on the afternoon of October 18, 1974. Before the conversation began, Robert Fripp played “Starless” from the latest King Crimson release, Red. As the last notes of the song faded, we began:

RF: King Crimson is completely over. For ever and ever.

IS: That’s sort of hard for some people to bear. When I first heard it, it was like someone dying in your close family.

RF: But why?

IS: I grew up on King Crimson. I was 15 when your first record came out and I bought it then and I’ve been buying every single one since then. I enjoyed it and now the thought of not having it anymore. . . you have the old records to listen to, but you know what they’re like, where every note is, just about, so a stopping point would be terrible. But if you say things will go on, that’s great.

RF: They’re not.

IS: What will happen?

Now normally, I don’t talk about history with anyone, but I appreciate that you’re a special case, you’ve taken a deeper interest in the band.

RF: I’m mixing a live album, recorded over a period of nine months from the end of last year until this year, with John.

IS: What’s going to be on that?

RF: Probably “Easy Money.” “Exiles” will probably follow “Easy Money” followed by a blow or something like that from Asbury Park. Side two, probably “The Talking Drum” into “Larks’ Tongue Part II” into “Schizoid Man.” Something like that.

IS: That leaves “Doctor D.” out.

RF: Yes. “Doctor D.” was never a complete piece. We were never fully satisfied with it so it won’t be used.

IS: Is there anything in the studio from the other bands or from this band which is left over? When you went into the studio you just recorded enough for an album?

RF: Just recorded what we needed, yes.

IS: Well, besides “Groon”….

RF: That’s it.

IS: So there’s going to be another Crimson album and then what?

RF: I’ll then do two composite albums, personal selections. Although there will be nothing new, it will be presented in a way which isn’t done normally in “Best of” albums. And it will include “Groon,” which of course most people don’t have.

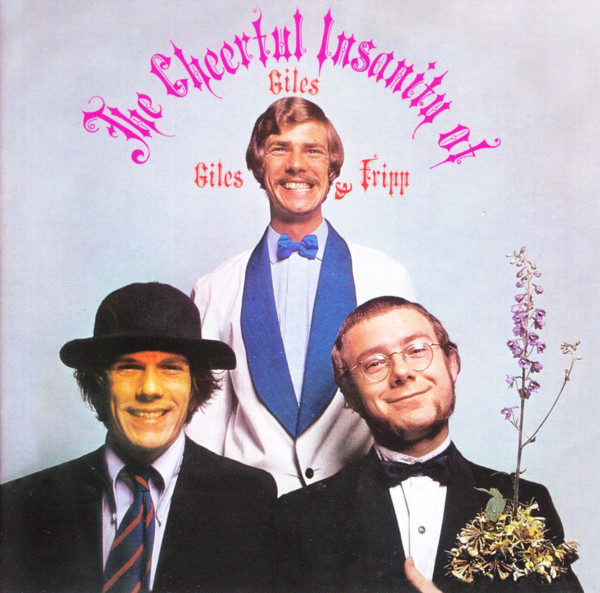

IS: What about [the album by] Giles, Giles & Fripp?

RF: [laughs]

IS: How do you feel about that now? I guess that was six years ago or so. Do you still look back at it and say, “Well, I didn’t like it” or “I did”?

RF: It has some very good things on it. I played guitar in those days.

IS: Your style sounds to me like a Wes Montgomery type.

RF: You’ve got to appreciate that I didn’t like a lot of the music on that album. I didn’t even want to play on it. Most of side one is nonsense. Pete Giles, for example — the only guitar sound he liked was Barney Kessel’s. Side one was Pete’s side. First half of side two was Mike and the second half of side two was me. That’s sort of a very rough guide.

IS: Was Giles, Giles and Fripp a big success?

RF: Oh, no. We sold 500 and something in England. I still get royalty statements. It sold one in Sweden, 40 in Canada.

IS: It was released in the U.S.

RF: Yes it was. Greg Lake managed to find a copy. It has a different cover to the English one. He threatened to have it blown up into a huge poster. I reminded Gregory that I had, and still do have, a few of his early publicity photos which include Greg holding a huge two-foot diameter plastic rose with a crown of thorns. I threatened reciprocal action with these.

IS: What’s on the American cover?

RF: I’m wearing a hat, a cap which looks like a Salvation Army cap and, well, it’s just different. Now normally, I don’t talk about history with anyone, but I appreciate that you’re a special case, you’ve taken a deeper interest in the band.

IS: Who discovered you?

RF: No one discovered us.

IS: How did you manage to put out the album?

RF: When I turned professional in the beginning of 1967, I was told that the Giles brothers had left Trendsetters Limited, which was their group, and were looking for a singing organist. Since I was a guitarist who didn’t sing, I went along for the job, and after rehearsing for a month and doing tape recordings in the Beacon Hotel in Bournemouth on a Revox, I said to Mike Giles, this is a bit of a joke, since I’d been working with him for a month. I said, “Well, have I got the job?” He rolled a cigarette in his mouth and lit it and puffed on it and said, “Well, let’s not be in too great a hurry to commit ourselves to each other.” From which you can gather that Mike never made his mind up about anything in his life. Anything that involved accepting responsibility was not really for Mike.

In September — this was about July — we moved to London. I knew that as a professional musician I had to go to London. It was the only place to go. And the Giles brothers, being professional for what, some four years, they knew the ropes, really, and I needed their experience, so we went to London. I got us a gig at an Italian restaurant, You’re not going to find this in many places, you know…. I got us a gig with Douglas Ward, a piano-accordionist, at an Italian restaurant in German Street near Picadilly.

But we had a week before that when we were in the Dolce Vita and at the end of that week the accordionist was beaten up and carried off to the hospital, where we visited him. He was burned up in a roundabout by these three louts, and he stopped his car and went back and sought them out and realized that he, little man with no muscles, white and puny, was no match for these three large oafs, who proceeded to duff him and kick him and make somewhat of a mess, so we visited the poor bloke in the hospital.

Anyway, we no longer had an accordionist to play with and we were suddenly thrown on our own in a situation that would not have normally been of our choosing, backing an Italian singer called Moreno, who I christened “Hotlips” Moreno, and used to introduce him, “Ladies and gentlemen! And now for your edification and delight, from Italy at great expense, we have for you alone, yes, it’s Hotlips Moreno!” And Moreno, this sort of five-foot-three Italian….

IS: Did he understand what was going on?

RF: Oh yes, he did, I’m afraid. He came onstage and he would say, “Please, please, you do not call me Hotlips.” We would go through his numbers and he’d write some of his own, and they were appalling. He had one or two progressions which just didn’t progress. Peter and I used to alleviate the situation by doing steps and swing guitars and make a very big to-do about some of the sequences which were really hideous.

I remember one diminished chord which came in as if by chance and I would do this lovely rippling diminished run finishing on the most inappropriate chord conceivable to man. And at the same time as this, we would swing our guitars in perfect unison, combining to narrowly miss Moreno’s head as he was singing. And one day, I remember, he looked around, knowing that something was going on, just to feel my machine brush his ear and narrowly miss. And Mike Giles said to us, “Look, you really have to tone this down, he’s not going to stand it for very much more. It’s gone too far.”

So the next set, we came on, and I’ll explain how we changed sets. There was a girl group, all girls, I think it was a quartet. They would sing, organ, drums, the whole lot, Italian…and the idea would be that one of them would go off, we would play “Blue Moon,” they would play “Blue Moon,” and we would play “Blue Moon” (laughing) and one of their people would go off and I would start… the organist would stop, for example, and I would start to play the tune and then the drummer would quickly move and Mike would come in, so that no one would realize that the band had changed! This was a great idea, but frankly, the difference in Mike Giles’s drumming and the Italian girl’s drumming was significant.

In order to get to the stage, we had an awful lot of people to go by, and we would get snagged along the way. So Pete and Mike would get to the stage, but I wouldn’t. I’d still be stuck in the back, struggling through a crowd…and all the girl singers, all the girl musicians would come off, leaving a sort of faltering “Blue Moon,” or just “Blue Moon” played on drums, or something like this, and I’d eventually struggle on and play “Blue Moon,” having completely blown the mood.

When we went off, Mike would go into some amazingly naughty times, which would be impossible for any of the Italian musicians replacing us to actually take over. Things like this, good fun. Mike’s warning told us we were tempting fate a little too much with Hotlips with our brand of humor and we broke into Hotlips’ set. Except there was no drumming, the drums suddenly weren’t there, and we turned around and there was Mike [laughter] with a maniacal, twisted smile on his face. Somehow he managed to cross his teeth… and his jaw, something like this… sort of flashing eyes, going through exaggerated motions of playing drums, but not actually hitting any of them, and it was one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen. That was just the end for Hotlips. He walked off there and then. So we had to finish off the week as a trio, with the girl Italians backing Hotlips Moreno, the Italian singer.

IS: That was probably more appropriate for him.

I’ve always been rather to the point in situations like this. Where other people would consider my actions tactless, I would consider them forthright and responsible.

RF: Yes, I think it was a lot better. We, meanwhile, got on with a set of beguines, for example “The Breeze and I” and “Spanish Harlem” beguines. The only difficulty was that we did them both in E, which was very nice as a trio where I could play open chords and spread out the sound. But Mike used the Italian girl’s kit, and the bass drum was tuned to E flat, a wholly inappropriate note. The root note for both “The Breeze and I” and “Spanish Harlem” was E, which Pete was playing in the same register as the bass drum, but a semi-tone away. The clash was hideous. It was really horrible. And we used to do “Mellow Yellow” with Mike singing….

We then realized that we were being rooked. Now bear in mind that the Giles brothers were probably two of the most cynical musicians one could imagine, having been through so much nonsense and dishonesty in the preceding four years that they didn’t have faith in anyone. In fact, Mike remains to this day the most suspicious man I’ve ever known. We realized that we were being robbed by the agent. We were being paid 30 pounds a week when in fact they were paying 40 pounds a week.

So I wrote the agent a letter and stated that he was being dishonest. I’ve always been rather to the point in situations like this. Where other people would consider my actions tactless, I would consider them forthright and responsible. The upshot of it was that at the end of the week we lost our job and I didn’t work for a year and a half, with very few exceptions and odd gigs. Mike, meanwhile, got a job playing with the Mike Moulton Five and Pete Giles did sundry things, including collecting supplementary benefits with me on a Friday in Camden Town, and did a few independent gigs with the Italian pickup band at the Dolce Vita. This left me free to practice up to 12 hours a day.

IS: Did you enjoy practicing?

RF: Oh, very much. Very much.

IS: What did you practice?

RF: Scales, chords, techniques, different solos. My sort of background as a guitarist is not one that is ever likely to be very widely known, which is a rather fortunate thing. I heard Roy Clark on the radio today playing “Twenty-First Street Rag.” That’s all the things I used to do: “Orange Blossom Special,” “Zarda’s,” “Nola,” all those kinds of things. My guitar teacher was an old banjoist from the ’30s. He also played guitar and mandolin. My background was what you call “corny,” sort of Nick Lucas, Eddie Lang acoustic guitar pieces. Some of them are very difficult.

The acoustic guitar, especially the plectrum acoustic guitar, is a completely different thing from rock ‘n’ roll guitar. They’re two instruments, electric and acoustic guitar, and I suppose there must be very few people who have a background in the classical period of classical guitar, which was in the ’30s, with Eddie Lang, and the end of the ’30s, Django Reinhardt and so on. But that was substantially my background, which is completely and wholly inappropriate for life as a rock musician.

I developed an interest in playing classical guitar pieces with a plectrum, the Cárcassi “Etudes,” the “Recuerdos de la Alhambra,” this sort of thing. If any of your readers would like to find out how good their plectrum technique is, I suggest they have a go at “Recuerdos de la Alhambra” by Tarrega and I think they’ll have a shock. Or Cárcassi “Etude No. 7” which is quite simple and straightforward, nowhere as difficult as the “Recuerdos.” Nevertheless, it sorts the men from the boys.

IS: Do you still play that?

RF: Yes, I’m practicing those pieces at the moment because it looks as if I might play an acoustic guitar on stage for the first time in my life.

IS: You’ve got Robin Miller and Marc Charig on the new album (Red). They were on the second and third albums.

RF: Yeah. Robin is co-principal oboeist with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Pierre Boulez. An amazing musician, quite frightfully good, in a different way than Mel, who is also good. I was rather, put-out isn’t the word, flabbergasted, awestruck if you like, by just how good Mel was on that cut. He just came in and did it and then went next door and did a session for Humble Pie. They were in the next studio. He’s in Alvin Lee’s new band which is rehearsing at the moment. Boz you know about. Ian MacDonald, shortly before our session, was tearing up tickets in the cinema, and who is now at this moment in New York.

I suppose what I’m doing is wiping out anything which prevents me from having relationships with any people I’ve worked with. I wouldn’t like to think there is anything within me, any failing of personality which… I wouldn’t be able to work with anybody again…. I went to see Boz at Central Park and Bad Company was good. I was so impressed and so pleased. His bass playing was fabulous, really nice. We’ve gotten really, well, happy to see each other again. I’d love to play with him, love to get him on an album.

IS: [Why] did David [Cross] leave Crimson after you played in New York in July?

RF: Well, it was mutual, I suppose, as in all these situations. No uptightness or unpleasantness involved. Sensitive musicians can’t work in the situation in which we were working. But a few, from time to time, do get as far as that. With David it was, I think, affecting his health, as it was with everyone who was involved with it. But David was too sensitive and gentle a personality for the rock business.

IS: What’s it like on the road?

RF: Well an awful lot is actually travelling. You have rehearsing, you have practicing, writing, and the actual playing comes last of all. That’s for free. You play for nothing. You get paid for travelling. And we were doing from 80,000 to 100,000 miles a year.

IS: That’s quite a lot.

RF: I mean, I must have done a quarter of a million miles in the past five years.

IS: Have you ever played anywhere besides Europe, England and America?

RF: No. For next year we had plans to go to Japan and Brazil. One of the fundamental facets of the personality of King Crimson was that the people involved, the personalities involved, had no consideration of anyone else involved.

IS: You mean, in the band itself?

RF: Yeah. Individuals would do their things regardless of what other people were doing.

IS: How can you keep something like that together when everybody wants to do something differently?

RF: It involves the discharge of a lot of energy, far more than I’m prepared to lose again.

IS: Did you ever play “Red” live?

RF: No. One of my two main regrets on Crimson ceasing is that we’ll never play “Red” live because it is primarily a live number.

IS: The ending is very moving.

RF: The ending? Actually the beginning, the song part, is my favorite.

IS: The beginning was sort of very…

RF: Ephemeral.

IS: … the mellotron would be playing and it would be very quiet and the low bass gives a very sad feeling…

RF: It’s very resigned. Very resigned. Do you want to hear any more?

IS: I heard some of it on the radio, the first cut, “Red.” Every one of your albums has a song like that which is sort of violent, in a way.

RF: Well, side one is the heavy metal side. It’s very definitely heavy metal. But I think it’s well done, actually. I think it’s very well done.

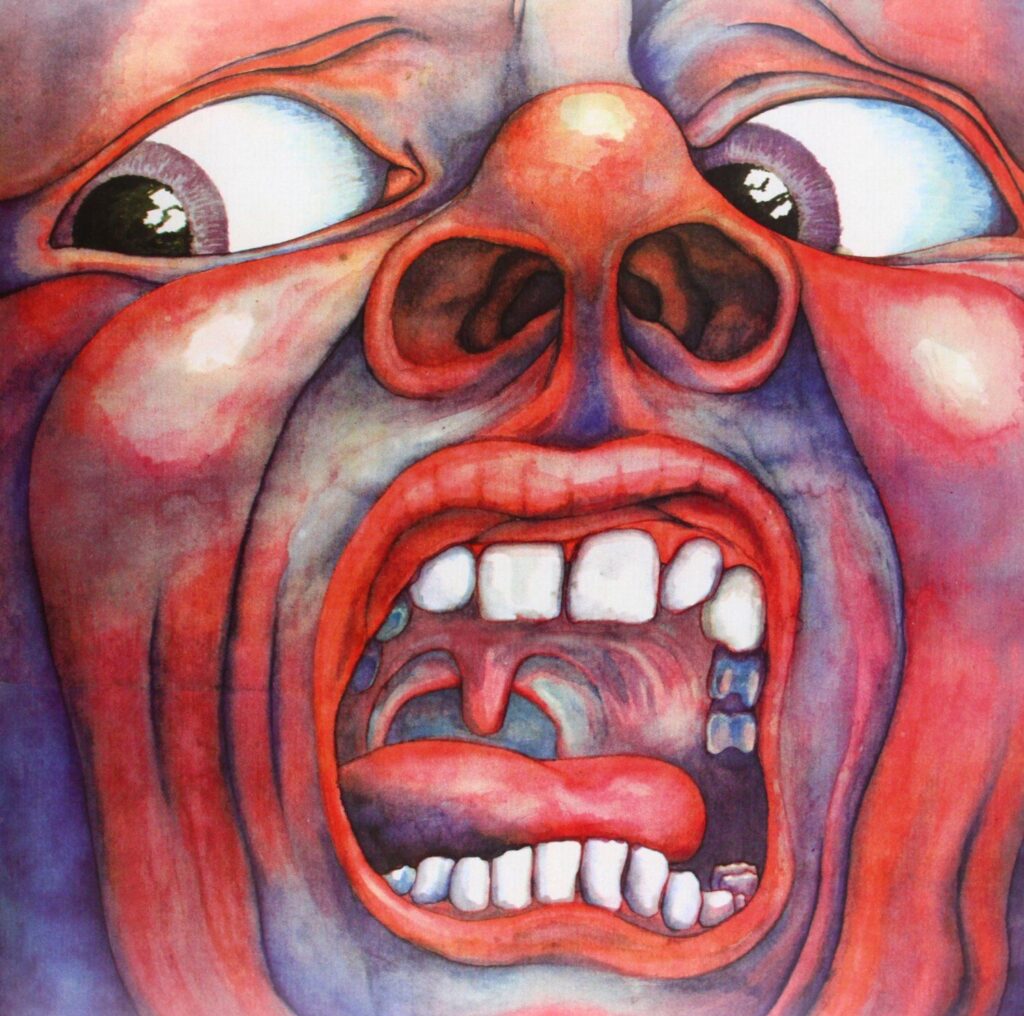

IS: On your first album you had “Schizoid Man” and then…

RF: Yes, the iron. It’s the iron, isn’t it?

IS: Right. I heard this and I thought this was very brutal; as if you’d get hurt just listening to it.

RF: [laughing] I wonder if they’d play that over here. I’d be surprised.

IS: [I understand you] played on Peter Hammill’s album Fool’s Mate.

RF: Yep.

IS: And John Wetton plays on…

RF: Everything.

IS: On everything?

RF: John’s on everything. Every time he goes over for a drink, a major band offers him a gig. Really. John is forming a trio at the moment.

IS: Who’s going to be in it?

RF: The drummer is a heavyweight, but I can’t tell you who. John is looking around for a good guitarist who’s heavy enough to take on the drummer and himself. That combination is difficult.

IS: I met someone recently who said there were two singles actually released from Giles Giles & Fripp: “One in a Million” and “The Elephant Song.”

RF: “Thursday Morning.”

IS: What was on the other side of “One in a Million?”

RF: The back of “One in a Million” was called “Newlyweds.” I can’t remember, other than it wasn’t on the album, or the version of it was different than the one on the album. Similarly, the single of “Thursday Morning” was different than “Thursday Morning” on the album because Ian MacDonald was on it, both singing and, I believe, playing clarinet.

We also recorded three more tracks for Decca as Giles, Giles and Fripp with lan MacDonald that were never released. One was called “Under the Sky,” which Pete Sinfield did. It was fabulous. And “Talk to the Wind” is with Mike Giles on drums, Pete Giles on bass, myself on guitar, Ian on flute, and the singing by Judy Dyble, who is on the first Fairport Convention album, and Ian. Those are the definitive versions of “Under the Sky” and “Talk to the Wind.”

IS: “Under the Sky” is on Sinfield’s solo album, but you say these are much better?

RF: Oh yes. Also, the “Talk to the Wind” is far better on the home-made tape I have than on the King Crimson album.

IS: How did you record it?

RF: At home. We did it on a Revox. It’s good stuff. But Judy left. She found me hard to work with apparently. You seem still interested in acquiring the single “One in a Million.” There’s no point in getting the singles because they are on the albums…

IS: Well, if they’re different versions…

RF: But why bother? These aren’t important, these are just small details for the collector, and you’re wasting a lot of good time getting into these small details. You’re taking it too seriously.

RF: How did you hear that Peter Giles was working as a computer programmer?

IS: I think I called someone here, maybe Simon Puxley or someone.

RF: Peter is now a solicitor’s clerk working for a lady called Mrs. Toswell. This is my latest information, which is six months old.

IS: Was he working as a computer programmer then?

RF: Yes, he was.

RF: There was another track we recorded as Giles, Giles and Fripp. There were three sides for Decca I was telling you about, three titles which weren’t released. One was “Under the Sky,” which was nice. The other was one by Pete Giles. What you need on this is the tape of the television show we did, the Giles brothers, Ian MacDonald and myself for Color Me Pop, a 25-minute television show in England. We recorded the music at home ourselves because it was better doing it that way. And there’s some good music there, let me tell you. It was a series, and we were one of the groups. After we completed the show, I think, I told Peter that I didn’t want to work with him anymore. But the music is of interest. It also has one track called “Drop In,” which was the third one we recorded for Decca that wasn’t released. It was meaty rock ‘n’ roll, with me writing the lyrics. The lyrics were dreadful.

IS: Really? You haven’t written any other lyrics…

RF: Apart from the Giles, Giles and Fripp album and that, no. Other than the punchline in “The Great Deceiver”: “Cigarettes . . . Chocolate cigarettes, figurines of the Virgin Mary,” which was mine..

IS: There’s a line which I heard you do live once, “Camel hair, Brylcreem… some stores full of antiquary.” What is – that line?

RF: That sounds like it comes from “The Great Deceiver.”

IS: Right

RF: Maybe this was in the early days of the song and John was just trying a few lyrics to see which felt best..

IS: Do you mean he would actually improvise onstage?

RF: No, but he might have…

IS: … or he had an idea of what he would do.

RF: Yes, yes. Your words are never complete till you’ve just sung them. Peter, in the studio, would be ferociously rewriting up until the last minute. “Court of the Crimson King,” for example, went through many, many different versions. I happen to like some of the earlier ones. The finished one’s also superb.

IS: That was put out here as a single.

RF: It got to number-98 as a single. But it’s just an abbreviated version of the album track.

IS: Also, “Schizoid Man” appears on..

RF: Nice Enough to Eat [a 1969 bargain compilation released in the UK by Island].

IS: Right. I guess that was abbreviated too, because it doesn’t have the introduction.

RF: I don’t think they’ve got the wind on it. Has it got the wind on it?

IS: No, it just starts off with the music. Is that supposed to be the wind or factory noises?

RF: The wind at the beginning? We had this pedal organ, which shows up at the end of “Crimson King,” and I said to Mike, why not just get the wind noises out by pressing the keys but not pushing far enough to get a note, so you just got the wind.

RF: The master for Walli Elmlark’s Cosmic Children of Rock [an album by the self-proclaimed white witch was produced by Fripp] is in Ronnie Scott’s Club in Frith Street, London.

IS: Is that ever going to be released?

RF: No.

IS: What was that?

RF: The music for it was a 45-second piece by Eno on synthesizer which I did in a way that lasted about 20 minutes. I just repeated it time and time again and cross-faded it in places. Side one has a percussion solo by Frank Perry, who’s a quite remarkable percussion player. But overall it wasn’t really a very good album. It certainly wasn’t a commercial one, so it was never released.

IS: What’s gonna happen now? King Crimson is finished and you say you’re going to be…

RF: You haven’t even asked me why it’s finished.

IS: Well, why is it finished?

RF: Why didn’t you ask me?

IS: I’m asking you now.

RF: No, I’d be interested to ask…

IS: Why…

RF: … to wonder why it didn’t occur to you. I want to know if that was the first question.

IS: I don’t know, King Crimson breaking up, it occurs every couple of years.

RF: You didn’t think this was the final one?

IS: Not really.

RF: I see.

IS: When David Cross left, I heard you were going to tour as a trio, and I figured that would be exciting because I’ve seen you perform as a trio onstage. At one show, towards the ending of “Schizoid Man,” David Cross actually walked off the stage and he wasn’t missed. The sound was sufficient, so I thought that should be interesting, playing those two albums as a trio. Then I heard that you had broken up, and it was sort of expected.

RF: All right, let me put the history, King Crimson and all the changes of the past six years into perspective. I’ve been experimenting with different ways of living and doing many things, and I’m continuing to do so. King Cirmson ceased to exist for three reasons. The first is that it represents a change in the world. Second, because the energies involved in the lifestyle and the music are no longer appropriate to my life as I live it. And thirdly, because the education that was King Crimson, the finest liberal education I could receive at that time, is no longer the best liberal education that I could receive.

First reason: it represents a change between the old world and the new. The old world is characterized by the unit of organization that has a very large body and a very small brain, is unwieldy and incapable of adaptation, and is wholly inappropriate for the conditions relevant to modern life. Examples of this unit are huge corporations, and the obvious example in the music business are groups that carry lots and lots of roadies and lots and lots of equipment. Unbalanced.

IS: Or a supergroup that isn’t accessible?

RF: When you get into inaccessibility, that’s not really the point.

IS: Can I give you an example? At the last Bowie concert in New York, I think there was only one photographer for the whole show and he was hired by MainMan.

RF: Well, I must say how reasonable and civilized that is, having spent most of my professional life in America having to fight off the irritations, the insensitivities of photographers who were quite happy to click away throughout the most delicate and difficult moments without any regard at all for the people on the stage. May I therefore laud what Bowie did. But I say that the organization which was surrounding David when I saw them in England was very large and unwieldy.

The characteristic organization of the new world is small, independent, mobile and intelligent. By intelligence, I mean as a measure of adaptibility to circumstances. You have a period of stress and tension when the transition between the old world and the new becomes most marked. For example, Atlantic [Records] here is a perfect example of the old way of doing things. No one knows what’s going on. Really breaking apart at the seams, don’t you think? Lots of people, lots of rooms, no one knows what’s really going on. Lots of graft, you know, going out and having drinks on the firm, wasting time, wasting money, which should presumably be the artists’. All this kind of nonsense can’t make it.

IS: I think I’ve been in that kind of situation. I worked for IBM, which is a worldwide corporation.

RF: That’s exactly it.

IS: I didn’t feel very lost in it because where I worked there was a department and there were about a dozen or 20 people, everyone pretty much knew each other and it was sort of one group.

RF: And how many other groups are there?

IS: Thousands.

RF: And how many…

IS: Our number was 42A and there was obviously a 42B and an 89J and all the other numbers in there.

RF: What I suggest to you, essentially, is that that is really an unwieldy organization and it can’t adapt at all.

IS: That’s true

America is going to collapse completely because it is so large and unwieldy. The only things that are going to get through are small, independent, intelligent, mobile small groups.

RF: This system is breaking down, I mean you couldn’t disagree with that, you only have to go out in the streets of New York to realize that this city, a large, unwieldy unit of organization, with no brain in command, is just not going to make it.

IS: What will happen?

RF: There will be a period of breakdown which will be most marked in the year 1990 and be most critical in the decade from 1990 to 1999. Sixteen years away. In an extreme situation, you could get the completė breakdown of social, political, and economic order, which you’re going to get anyway, but it may not be final, if you like. Once again, in an extreme situation, you could have a nuclear war.

By the year 1985, you’re going to have serious privation in every sector. By the year 1990, you won’t have private automobiles and you’ll have a very, very difficult situation which will make the Depression of the ’30s look as if a really great time was had by all. In America it’s most marked, and this relates to your values which are certainly the most inappropriate and mistaken values anyone could hold.

The American idea that the only thing to live for is a “fast buck,” that the only thing to work for is not to work at all, is nonsense, complete nonsense. Because of this attitude, which has sadly affected many other countries in the world as well, your country is going to disintegrate. You have at the same time a very strong development in terms of spiritual communities and a large number of people, in numerical terms, compared to England for example, who are working on making the transition between the old and the new.

America is going to collapse completely because it is so large and unwieldy. The only things that are going to get through are small, independent, intelligent, mobile small groups, units. In the ’80s it will be, I think, a continuation of the drive towards spiritualization, but in a real sense. Getting out of your brain and saying, “yeah man that’s really groovy” doesn’t really take you very far, but what it does do is create a situation where a population is sympathetic towards those who are working in a certain area. For example, the majority of conservative Americans would not let certain things take place. Liberal maneuvers could not take place with the consent of much of American popular opinion. However, in 10 years’ time, the heads of the ’60s will be in their forties and will be forming the backbone of America. If they are open to and sympathetic to people who have a more real interest in changing America, then you will have a situation which, although it may not help actively, is nevertheless passively open to it.

IS: Liberal things won’t happen because America is mostly conservative now. The people who were radical in the ’60s will have become moderately radical or liberal in 20 years.

RF: What I’m suggesting is that they will be more aware that there is more involved in living than satisfying purely immediate needs and desires and gratifications.

America is going to collapse completely because it is so large and unwieldy. The only things that are going to get through are small, independent, intelligent, mobile small groups, units.

RF: If you knew that tomorrow you were going to be dead, wouldn’t you do something today?

IS: I don’t know what I’d do today.

RF: I suggest, whatever you did do, you live to the full. If you were going to have a hamburger and you thought “Christ, this is my last hamburger,” you’d cherish every bite.

IS: Right.

RF: The majority of the people are not going to make it through.

IS: But you can’t live as if you’re expecting to die.

RF: Have you read Don Juan?

IS: I have.

RE: Death lives on the shoulder. This is what I’m talking about. Have you read the New Testament?

IS: Not really.

RF: Where Paul talks about dying daily. Exactly the same idea.

IS: Dying daily could be going to sleep.

RF: Dying daily has to do with breaking out of sleep. It’s an assertion that man lives his life in a condition of sleep and dying daily is where man actually wakes up. One can only live fully if one knows that tomorrow one will be dead. Puts things in a completely different perspective.

IS: But we have to make believe that we are going to live.

RF: That’s nonsense. We don’t have to make believe at all because it’s not necessarily true. In fact, for a lot of people, it isn’t. This is a vital point. Because when you do live with that realization that tomorrow you will be dead, your life takes on a totally different character. You see, nothing is guaranteed.

RF: Where do your parents come from?

IS: From the Ukraine.

RF: Yeah.

IS: Do you know where that is?

RF: Well, out there.

RF: I don’t think you’ll hear very much from me.

IS: What do you mean?

RF: I think you’ll find that I might just disappear.

IS: And just have albums appear in record stores every so often?

RF: Maybe not even that.

IS: Wow.

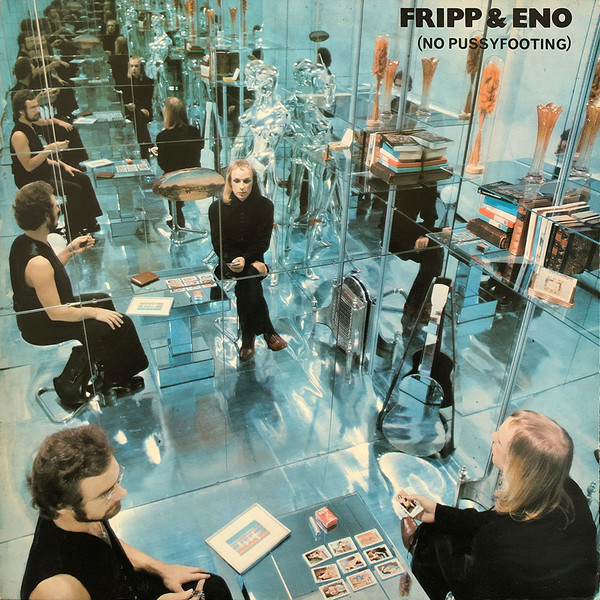

RF: You must wait and see how much is wanted. I respond to people who want something. You see, if you do something like the Fripp & Eno album [(No Pussyfooting)], and Atlantic turned it down, I don’t think I have very much in common with Atlantic. In fact, I have nothing in common with Atlantic.

IS: Are they required to put everything out?

RF: No, they’re absolutely not.

IS: So why…?

RF: Well, if they don’t want to, I don’t want them to put it out. The album has a meaning for me.

IS: I was under the impression that you went into the studio and made it very fast.

RF: We made side one at home. We just took a lady friend around to Eno’s, had a glass of wine and a cup of coffee, plugged in, and did side one in 45 minutes. Two guitars, that’s all. No amplifier, just me, my Pedalboard, direct-injected into two Revoxes. Side two in a studio, recorded in an evening. Took it right into another studio, mixed it, put it. together, there you go. That was the album.

IS: I was thinking that to have some meaning you have to work on it for a while.

RF: I worked on it all my life. It was the most perfect expression of whatever I’ve done or thought or felt. In other words; if anyone doesn’t like side one, they won’t like me. So when Atlantic turned it down, in fact, they turned me down. Which doesn’t make me uptight, or bitchy, or cheesed off or anything like that. I just appreciate that for what I will be doing in the future, the appeal will be limited to people of certain types. I don’t feel the need to bang my head against a wall, to rush around America again. If the people want me to come to America, I might, because I’ve got a lot of things I want to do as well.

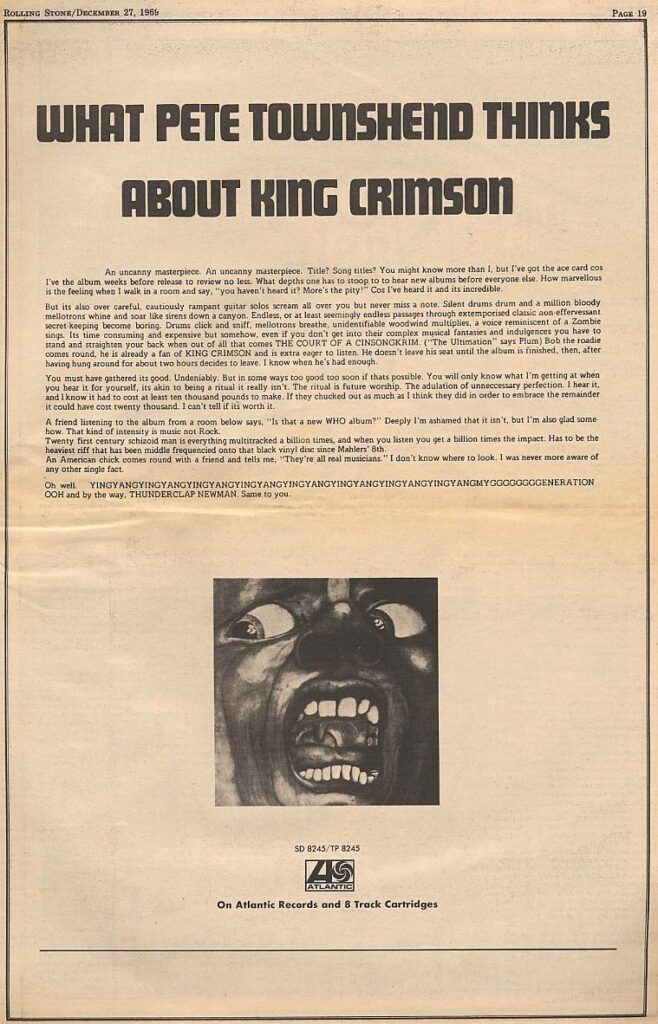

IS: One of the first advertisements for the King Crimson album was this ad.

RF: Oh, right. This is what Pete Townshend wrote.

IS: How did you get him to write that?

RF: Well, I had this idea for a liner in an advert, which was to ask Pete Townshend, to give him a record to review. And he really liked the album. And this is what he wrote, unsolicited. That’s just his reaction to it. It’s difficult to tell you the kind of excitement there was in England when the band came out. It only really got to that pitch in America afterwards, when the group broke up, but in England, the feeling was quite amazing.

If you want the handy sentence, here it comes again. It’s the harmonious development of all the parts of my being simultaneously and in a hurry.

And since it was my first professional rock group, the first time I played live on stage in a rock group, I didn’t know how rock groups did anything. Ian had been in the Army for five years, was suicidal, neurotic. As we all were, I suppose. Mike Giles came from the Orchid Pearly and cabaret bands. Greg Lake was the only one who had any experience as a professional rock musician and that was with the Godz, who eventually became Uriah Heep. So if you like, think of Uriah Heep as Greg’s rock background.

IS: You were going to make some point about Trouser Press?

RF: Oh, that’s right, yes. Where you refer to me as a “cold unemotional genius” in the star system. Well, look, this is complete nonsense. I mean, do you realize that? Do you realize, first of all, that I am not a genius and second of all that I am not emotionless?

IS: That’s the sort of impression that one gets of you.

RF: Well, surely you can see a little more than that.

IS: I don’t know. I think I came in here pretty openly, I don’t know how I’m going to come out.

RF: Fff…well…ehh…Well, whenever someone has a mind and uses it, I suppose there is a tendency for him to be regarded as calculating. However, not only am I not my body or my feelings, I am also not my mind. To regard me as a genius is nonsense. To regard me as emotionless is somewhat lacking in observation and penetration.

IS: I think that observation arose from watching you onstage, where you’re just very intently playing and you just barely look up to see the band and you hardly ever look out into the audience. If you were in a bell jar of some sort, it would create the same impression. You seem distant, in a way. But the other day I was reading some article in Melody Maker: “Robert Fripp Super-Stud,” and they said you were trying to change your image.

RF: That reflected me as I was then. It was also great fun to see how many people, personal acquaintances as well as people along the way, were quite surprised, quite shocked, to find that I was a young man with developed carnal interests, which were not held in perhaps as great a check as they should have been. It is also interesting how many young ladies, having read the articles, were interested to find out a little more.

IS: What are you now?

RF: That fashion of living is no longer appropriate to my life as it is now lived.

IS: Can you further tell me something about what your fashion is now?

RF: I’ve already told you.

IS: All right.

RF: If you want the handy sentence, here it comes again. It’s the harmonious development of all the parts of my being simultaneously and in a hurry.

IS: Do you think you can do it in a hurry? I mean, is the reason why you’re doing it in a hurry because you’re worried about what will happen?

RF: There are some techniques to do it in a hurry. Yes, that’s exactly right.

IS: How does one find out about these techniques? Does one just simply have to look for them or can you tell me now?

RF: When you spend a sufficient period of time looking, but looking in a certain way, which is more than a casual interest, you find yourself presented with an opportunity, which you then take or not.

IS: I guess the analogy would be my looking for a copy of Giles, Giles & Fripp and finally getting one.

RF: Yeah.

IS: It eventually comes around.

RF: You have to actually work.

RF: I’ve decided to give some guitar lessons.

IS: To musicians or non-musicians?

RF: To guitarists of medium and advanced capabilities. Not beginners. Whereas the King Crimson idea represented an attempt to influence and to reach a lot of people, the ventures for the future, the Eno situation, the guitar teaching, and other activities will seek to influence a smaller number of people but nevertheless will have a greater effect in time. In other words, instead of striking at the base of the pyramid, I’m striking higher up. I would rather give guitar lessons to a half dozen guitar teachers than 60 of their pupils…. I’m working on a guitar technique that doesn’t seek to give the player control of his guitar as much as control of himself.

IS: You have an interesting style of playing. You pick strings with both hands.

RF: The distinguishing feature between myself and most other guitar players is that I have two hands and have worked hard over a period of 13 years to develop my righthand technique, my plectric skill. Most electric-guitar players, in fact, have no plectrum technique, and most of the movement is done by the left hand. Which is very good for phrasing and so on, but it means that the player is not in control of his instrument.

IS: When you were playing onstage what did you put your guitar through? Did you have it directly into the amp?

RF: It went through a Fripp Pedalboard.

IS: What’s on that?

RF: Oh, these things aren’t important.

IS: The last gig you did in New York here, did you know that that was going to be the last one?

RF: Well, I knew it would be the last one for David, but at that point I had considered touring with the band. We considered experimenting with a number of different forms, as a trio and as a quartet with lan MacDonald. But four weeks ago yesterday [that would be 9/19/74] I decided that was it. And, I have no real regrets other than not playing “Red” live, and not going to Brazil and Japan, I suppose. That sort of thing. But no real regrets because the decision was a right one. The kind of feeling I’ve got from other musicians is that they rather envy what they see as, well, my courage. I’m not saying that, I’m not considering it courage, I just continue to consider my action wholly sane and appropriate to the time. But there are a number of musicians I know who wish they could do je same and of course they can.

IS: That’s true. King Crimson, speaking from a record industry point of view and an audience point of view, reached, I guess, a high point, or re-reached it. I thought that the first album was excellent and from there it went down a little until you reached Islands, which was very different, and then you had Earthbound, which showed what, maybe, American touring was like, but then…

RF: Earthbound wasn’t King Crimson.

IS: I think in a way it was because it sounds like an awful bootleg.

RF: It’s King Crimson’s own bootleg.

IS: Right, and it sort of, it sort of represents, well, this is what it really is like, it’s just sort of really bad, it’s, I mean…

RF: It wasn’t King Crimson.

IS: I think what the album stands for…

RF: The album was released to show why the band broke up.

IS: Yeah, right. I guess that’s what I was trying to say.

RF: Well, you succeeded in saying it then.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.