By Ira Robbins

Excerpted from Volume One of an anthology and memoir, now available as an E-book from Amazon.

Some memories of Trouser Press:

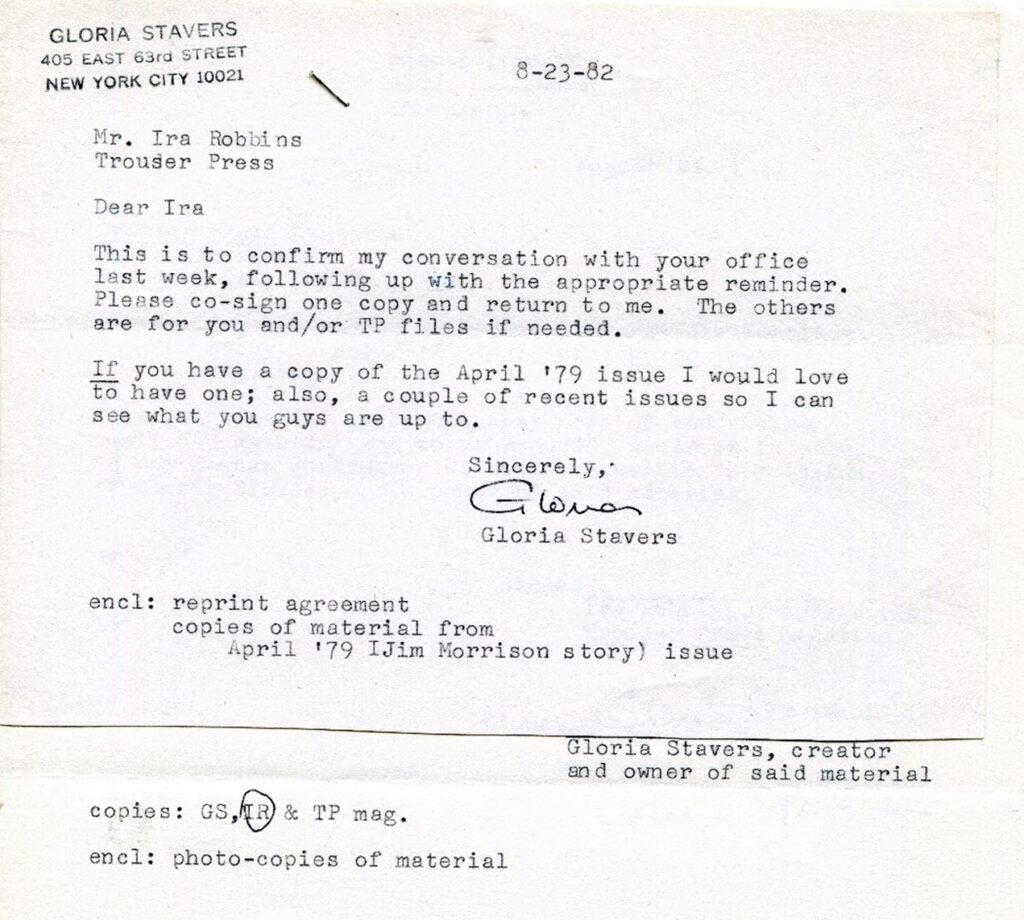

In April 1979, Trouser Press ran a Jim Morrison article by Gloria Stavers, whose byline I knew from reading 16 Magazine, where she was the editor and sometimes referred to herself as GeeGee. It was a thrill to have a small interaction with someone I’d looked up to as a kid. I don’t recall the reprint arrangement that led to this note (she died the following year at 55), but she was a great character and lovely to know.

We had plenty of other adventures:

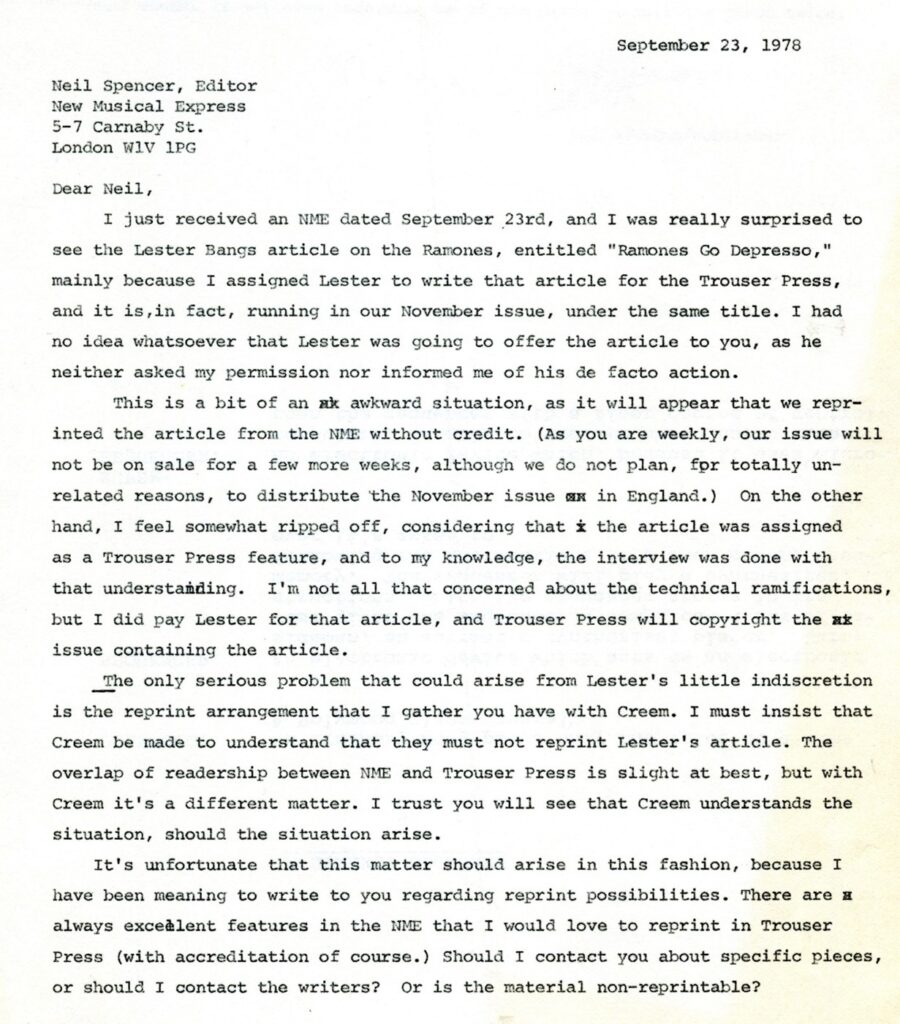

◆ The one time we got Lester Bangs (R.I.P.) to write for us, he sold the Ramones article we assigned to the NME without crediting TP, so it looked like we reprinted it, rather than the other way around. He was pretty indignant at our displeasure, but given our paltry pay scale, we had a lot of nerve to be outraged. The article appeared in issue 33 (November 1978).

I wrote to Neil Spencer, editor of the NME, concerned that the piece might end up in Creem. (The two publications had a content sharing arrangement.) Neil is a fascinating and colorful character who I’ve since met through my London friend Pete Silverton. Neil is now an acclaimed astrologer in England.

◆ Dave Schulps’s phoner with Elvis Costello — his first contact with an American journalist — ended abruptly when Elvis’s estranged wife called on the other line. (That wasn’t his only hasty exit. After Elvis made his regrettable racist remark about Ray Charles, he held a press conference of sorts in a room at Black Rock (CBS) in New York, abjectly sweating through questions from a roomful of African-American journalists unimpressed by whatever it was he was supposed to be famous for. As Elvis made another hapless attempt to explain his drunken stupidity, I happened to glance at the back of the room and saw his manager Jake Riviera silently draw a finger across his throat. He’d seen enough. Elvis instantly clammed up and walked out of the room.)

◆ The call I got in the office one day from a woman I knew who said she was in a hotel room somewhere, had just fucked Iggy Pop and was delighted to confirm the rumors about the size of his cock.

◆ Scott Isler’s attempt to honor Devo’s bizarre request to be interviewed by Linda Lovelace for the cover story of issue 70, which ended when her boyfriend-cum-manager Chuck Traynor threatened Scott’s life over the phone just for calling. Her seemingly safer replacement was William S. Burroughs, but the resulting meeting of the minds at Burroughs’ New York City residence, the Bunker, proved a lot less edifying than we’d hoped: they spent a lot of their time together discussing the purchasing and consumption of recreational drugs. Just to amplify the disappointment, Burroughs amanuensis James Grauerholz later included our interview in a book without seeking permission or giving credit. Years later, that led to it appearing, again sans credit or permission, in Italian Rolling Stone.

◆ The time Wendy O. Williams — towering on platform boots and probably barely clad — strutted into our shabby Times Square office to drop off a Plasmatics ad.

◆ Dave Schulps’ encounter with Jimmy Page that resulted in the most informative and expansive historical interview the guitarist has ever granted. A sitdown set for the Plaza Hotel in New York during Led Zeppelin’s Madison Square Garden stand in 1977 kept getting pushed back until the band decamped for Los Angeles and Dave followed. He was kept waiting by the pool for the better part of a week until Page finally deigned to talk. The cover story we got out of it was well worth the effort, but it led to insane deadline anxiety at the time.

◆ A disagreement over whether or not we could run yellow ink in a half-page Jonathan Richman ad that led gangly ad salesman Joel Webber (R.I.P.) and I to wrestle each other over a desk.

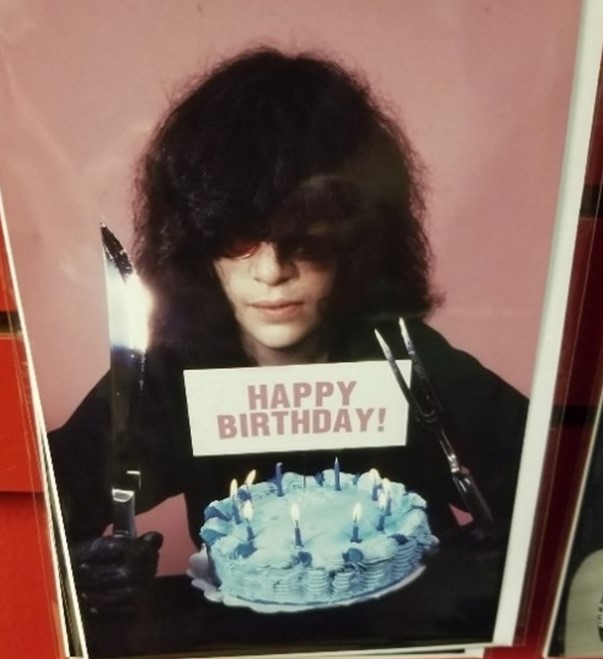

◆ The Joey Ramone cover shoot David Godlis did for our final issue, during which the candles on the cake set fire to the “10th Anniversary” sign we had typeset for the occasion. Godlis was able to cobble a replacement together on the spot, but then some enterprising greeting card company got ahold of the image and retrofitted it for wider and more durable appeal. (I hope Godlis got paid.)

On March 23, 2014, we threw a 40th Trouser Press anniversary and reunion party at Bowery Electric in New York. Bands played, friends who hadn’t seen each other in decades got to catch up and we all had a wonderful night of memories and music. I gave a speech to express my gratitude. Re-reading it now, there isn’t a word I would change.

◆ ◆ ◆

The story of Trouser Press resembles the story of a band. We met in high school, got things going in college, had fun for a while, involved a lot of great people, made no money, broke up and then got famous.

What began as a whim on a southbound #1 train ended up consuming my life for 11 years. And, ultimately, brought us all here tonight.

Thanksgiving 1973. Dave Schulps and I — besides encountering Bob Dylan in Village Oldies — hauled ass up to Yonkers for a record collectors hang with a bunch of strangers who, like us, were into British Invasion bands. We weren’t full-on collectors, more like amateur trainspotters, but that got us in. We ended up riding downtown with one of the people we met there, a redhead named Karen Rose, who worshipped Jeff Beck and had edited the Brooklyn College newspaper. By the time we got off the train, the three of us had decided to publish a fanzine. I was 19 years old, and it just didn’t seem like that big a deal.

In creating Trouser Press, we billed ourselves as outsiders — “an alternative to the alternate alternatives” is how we put it in a pre-publication mailer. “We have nothing to alienate anybody — no famous writers, no big names, no money, or anything that might make us elitist (or successful).” Truer words…

Using my father’s mimeograph, a rented Selectric typewriter and a T-square wielded by High School of Art and Design student Barbara Wolf, we pulled together a first issue, with articles to match the March 1974 concert schedule in New York. Our idea was to hawk the mag in front of venues with articles about the bands playing there. So come March 9, 1974, we planted ourselves in front of the Academy of Music on East 14th Street, at a show featuring 10cc, Brian Auger and Rory Gallagher.

The opportunity to rave about music we loved was pretty seductive. And the odd perks — a personal letter from Pete Townshend in response to the first issue, free records, a paid subscription from Gene Simmons — made a future seem possible. In short order, our all-volunteer army grew to include Jim Green, Scott Isler and Sue Weiner.

We didn’t invent anything, but we knew who to emulate. Crawdaddy, Rock Marketplace, Bomp, Zigzag, Creem, the NME — that was where words about music changed things for me. Paul Williams, Lenny Kaye, Greg Shaw, Nik Cohn, Nick Kent, Nick Tosches, Alan Betrock, Billy Altman, Ellen Willis, Richard Meltzer, Joe Fleury, Lillian Roxon — they were as much my heroes as the bands they wrote about.

We never had a clear sense of what the magazine meant to anyone. Until we stopped. Since 1984 I have been amazed by how durable a concept, a memory, an ideal Trouser Press turned out to be. Whatever that is, Trouser Press is more of it now than it was 30 years ago, when our obituary ran in Rolling Stone. “Voice of pop-rock underground folds after 10 fan-filled years.”

And fans we were. Musicians told us we knew more about them than they did. We came prepared, and despite our deep-seated snark, we always gave artists a fair shake. If it was Moogy Klingman patiently enduring the questions of three rank amateurs, Steve Harley challenging me over stuff I’d read in the British weeklies, Hugh Cornwell of the Stranglers being a complete prick to staff photographer Linda Danna, Lou Reed playing his asshole character to the hilt with Scott or Jimmy Page giving Dave the most detailed accounting of his career by the pool at the Beverly Hilton, it all became Trouser Press.

None of us set out to be in charge, we just fell into roles, roles for which we were wholly unsuited. I was certainly not cut out to be a businessman, and I take full responsibility for the failure of Trouser Press to become a sprawling media empire, the Pitchfork of its time. But the people involved all had talent, spirit and imagination: art director Judy Steccone, Kathy Frank, Steve Korté, photographer Ron Gott, Mark Fleischmann, Louise Greif, Wayne King, Kenn Lowy, John Gallagher, Dan Zedek, David Fenichell, Craig Campbell.

What ultimately made Trouser Press worth its ink was the incredible world of creative talent we stumbled onto. The list of greats who placed themselves in the pages of Trouser Press still shocks me. David Fricke, Ebet Roberts, Mick Farren, John Leland, Jon Young, Gloria Stavers, Laura Levine, Pete Silverton, Jim Sullivan, Tim Sommer, Bill Flanagan, Marianne Meyer, Steven Grant, Dave Godlis, Pete Frame, Jim Sullivan, Paul Rambali, Mitch Kearney, Laura Fissinger, Kurt Loder, John Walker, Marilyn Laverty, Cary Baker, Amy Horowitz, Savage Pencil, Barbara Kagan, Roman Szolkowski….

And they did it for peanuts. I am embarrassed at how little we were able to pay such valuable people. I have no defense for that except that we didn’t have any money. Simple as that. We operated as a collective of sorts, and everyone’s contribution was part of a group effort to accomplish something worthwhile. I am gratified and relieved that many of them went on to far more lucrative success.

We even had world-class interns: Tim Sommer, Fran DeFeo, Pearl Lieberman, Linda Walker, Eric Hoffert, Adam Auslander, Jay Paquette, Miriam Kuznets and others, many of whom built distinguished careers in the music world and beyond.

Speaking of beyond: Karen bowed out of an active role in the magazine after a few years and went on to found Rock Read, a company of her own that sold music books by mail order. An Amazon of the ’80s, you might say. Like many of the people who knew and admired her, I was shocked by her death in 1989 from cancer.

Jim Green brought his gangly Berkeley pal Joel Webber into the Sam Goody’s record store where we both worked in early 1976, and I hired him on the spot to be our ad director. With his energy, his bravado and his height, Joel was a boon to our fledgling operation, although we did once end up throwing each other over desks in our tiny Times Square office. I watched in awe as he went on to a career as a director of the New Music Seminar and an A&R man at Island Records. Joel’s 1988 funeral was a heartbreaker.

Mick Farren, who died last summer, was a true rock legend. I never imagined we deserved to have him write for us, certainly not for what we were able to pay him, but I was proud as hell every month when he came in with his Surface Noise column. Mick was a great writer, but he was much more than that. A crucial ’60s figure in British politics, bands, culture and publishing.

Back to the living, and then I promise I’ll stop. Dave Schulps and I have stayed friends for 45 years, and I can assure you that I would not be here tonight if not for him. He shaped my musical taste and redirected my life. Without realizing it at the time, we took a leap together that changed us both. We share a lot, we do — just ask us to recite the dialogue from Putney Swope in synch if you want proof — but we’re very different people, and a couple of years spent putting out a magazine made some of those ways abundantly clear. I had the perseverance — or lack of imagination, call it what you will — to stick it out for 10 years, dealing with the nuts and bolts of running a small business, while Dave went off to manage a band before settling into the career he still excels at: reporter, interviewer and writer.

Since the magazine ended, I’ve gotten a lot more credit for Trouser Press than I deserve. Dave is not the only other person who gave the magazine its truth and soul, but he certainly leads that list. Simply put, Trouser Press would not have existed — or mattered — if not for him. ◆