Behind every album there is an unseen story, the sausage-making truth of how the music that comes out of your speakers (or airbuds) got made. Once absorbed, albums exist in your head, well removed from how they came to be there. Like the visions we conjure up of characters in fiction, the sounds may suggest something to us, but those are just our own fantasies about the creation of art, not anything real about the artistry involved.

The process has changed enormously since the early days. The first Beatles albums, the ones that have entertained at least three generations of listeners now, were made by a band in a big room playing songs a few times each into a couple of microphones while lab-coated technicians adjusted disc-sized volume dials on a console. A couple of days work, and there’s one done for the ages.

While session players may have added efficiency, album recording quickly got a lot more complicated: more tracks, more time, more money, more cooks in the kitchen, more ambition, synthesizers, growing artist power. And then technology came along: Fairlights, sampling, MIDI, automated mixing, digital recording and effects. In recent years, even studios have grown ancillary: a lot of it is now done at home on GarageBand or ProTools. Perhaps not so much anymore, pop music history is rich with sagas of vast waste, of false starts, freakouts and meltdowns, breakups, drug abuse, creative clashes, mad escapades and lunatic experiments. It’s a fascinating subject, different in a thousand ways but ultimately all the same. Someone has music in their head, and giving it audible life can be a trauma. No surprise that “making of” stories have become an essential form of music journalism, the subjects of countless VH1 specials.

Of course, the majority of recording projects are completed without incident, hard work by determined artists seeing their sonic vision through. But names like Brian Wilson, Guy Stevens, Phil Spector, Tom Scholz, James Hetfield, My Bloody Valentine and the titles Skylarking, Tusk, The Seeds of Love, Exile on Main St., Let It Be and Chinese Democracy are all inscribed in the souls of recording studios that witnessed untold expenditures of cash, sanity, time, angst and strife. And they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

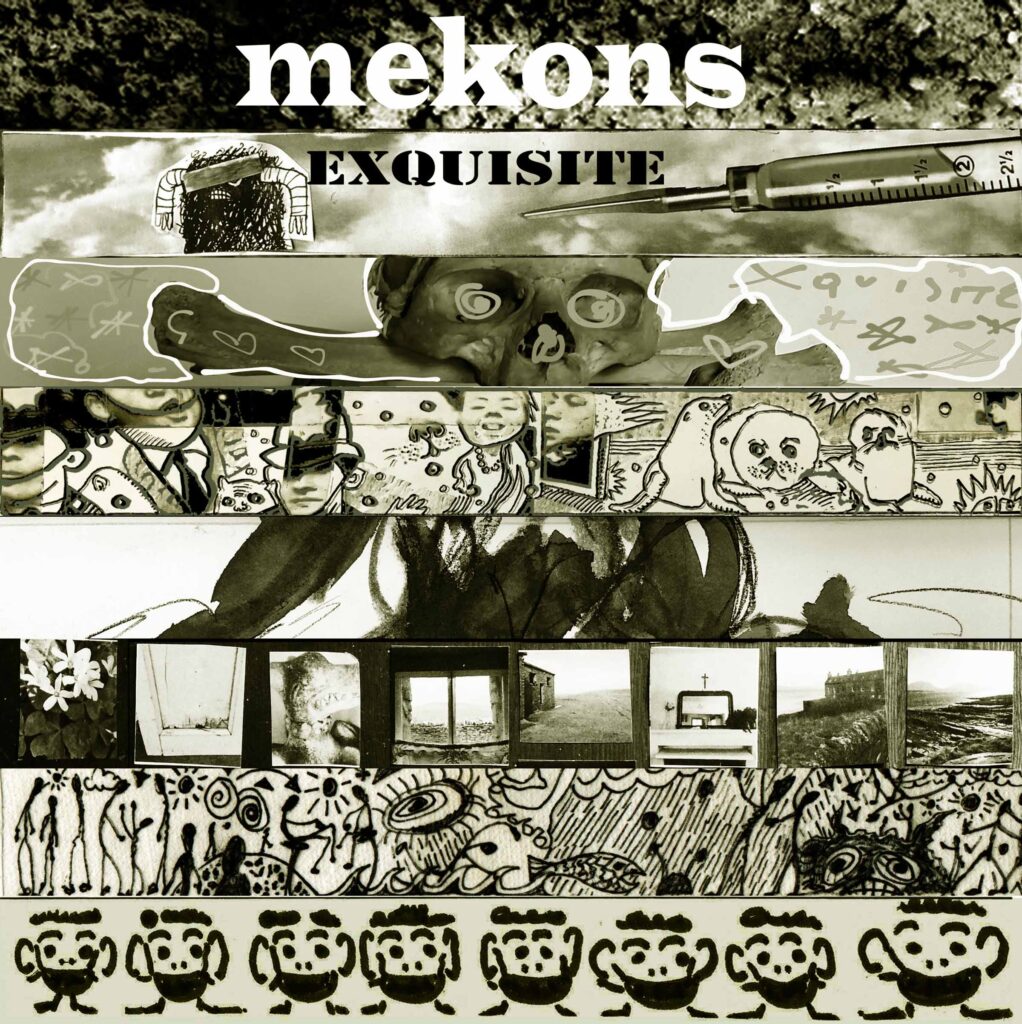

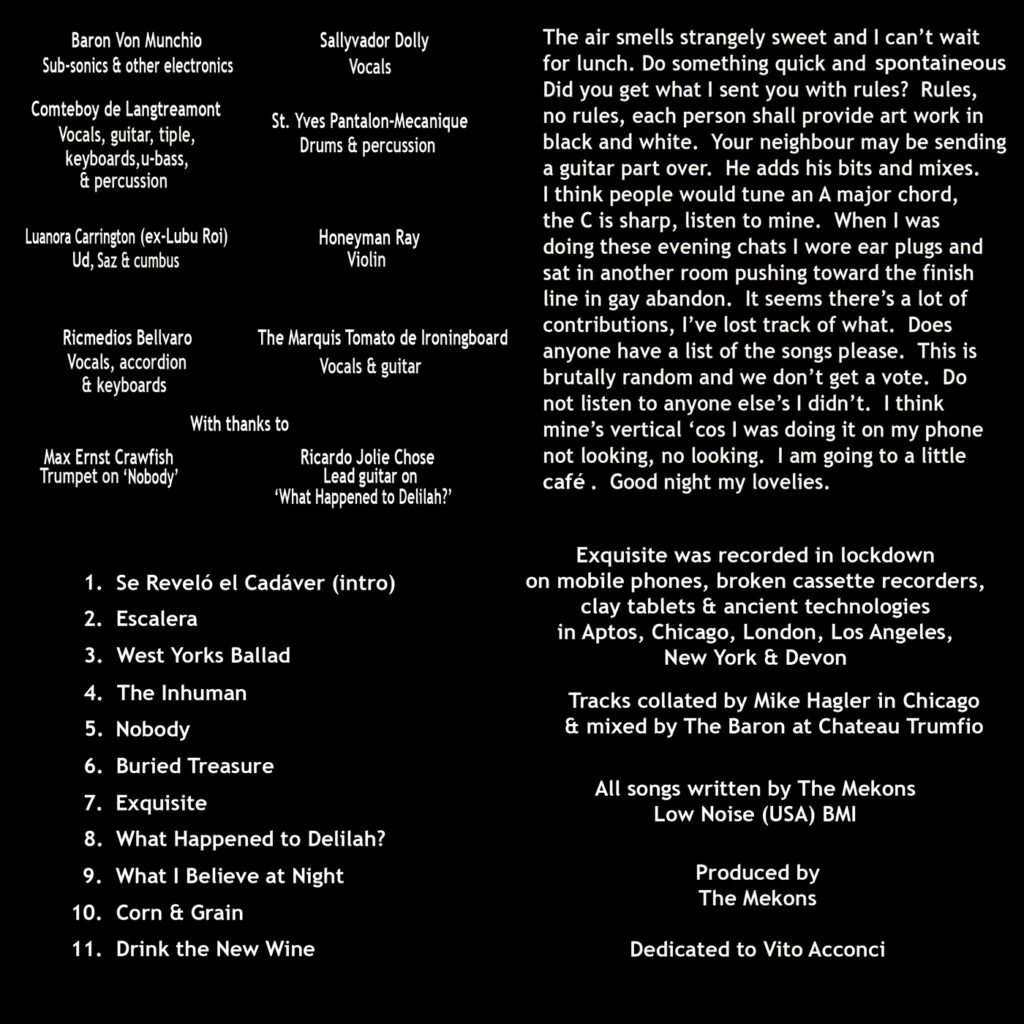

The Mekons have long been an exceptional outfit for many reasons; their latest release, Exquisite (available via Bandcamp download starting June 19th), is another link in the group’s inimitable chain. Responding to the unique situation of home isolation, they dove in and made a record anyway. (And people thought that Elton John and Bernie Taupin remotely collaborating on songwriting was some creative miracle.) I’ll let the press release explain how an album employing the Dada creative tool known as “the exquisite corpse” came into being:

“Locked down in various locations stretching from the West Coast of California to the East End of London, Mekons sang and played into their cellphones, E-mailing, uploading and Whatsapping their wailings, beatings, scratchings and strummings across the globe. Exquisite was recorded in splendid physical isolation on mobile phones, broken cassette recorders, clay tablets and other ancient technologies in Aptos, Chicago, London, Los Angeles, New York and Devon in April and May 2020. Mike Hagler assembled the results in Chicago, which were mixed by Dave Trumfio in LA.”

It’s inconceivable to me how such fliply outlined creativity was actually organized and executed; what’s more, there’s no telling who did what here. (The bandmembers credited on the “back cover” are pseudonymous, although the bumpf fingers the guest guitarist on the rollicking “What Happened to Delilah” as Dick Taylor of the Pretty Things and the trumpeter on “Nobody” as Max Crawford). If the process sounds like a recipe for a mess, rest easy on that account — plenty of bands have made albums under normal conditions that sound far less accomplished than this.

Exquisite is jolly good; like a one-disc Sandinista! — rough-hewn, stylistically and culturally diverse, uplifting in spirit and wittily weird (or is that weirdly witty?). The breadth and quantity of music these fine folks have made, know and can play is intimidating, but this is a thoroughly approachable and enjoyable collection. As I haven’t been keeping up with the Mekons of late, I can’t say where this fits into the canon, but if they can make a record this good under pandemic conditions, I can’t wait for the next one. And if we ever need anything to remind us of how we survived this terrible chapter in human suffering, of music that refused to stay unborn, singing back the devastation, this will do nicely.

The band’s decision to release the album on Juneteenth means Bandcamp will donate the commission it normally takes from artists to the NAACP. So that sweetens the music an extra bit.

The exquisite corpse game originated not with song but with prose; one person would write a line of a poem or a paragraph of a story and then hand it off to another, who added to it, generally without reading all of what was already there. In keeping with Dada’s embrace of humor and randomness, the result is a sequence of non sequiturs often more amusing and thought-provoking than a single author’s linear creation.

I did a few of them in correspondence with the Chicago poet/singer Lydia Tomkiw of the band Algebra Suicide. A truly remarkable character, Lydia is gone now, but Poems, a marvelous collection of her writing, edited by Dan Shepelavy, has just been published. It’s a rich taste of a unique voice, and I’m delighted to have been able to supply an appreciation of her musical efforts in partnership with Don Hedeker, now of the Polkaholics.