Long (and rightly) thought of as one of the star-crossed British Invasion bands that never got its due — a brilliant, multi-faceted delight for discerning aficionados and just a couple of classic singles to the general public — the Zombies (obvious puns on the name not needed) have mounted quite a second chapter over the past two decades, touring, recording and ultimately being enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2019.

Three new vinyl reissues due out this Friday from Concord attest to the continued interest in the band’s ‘60s work:

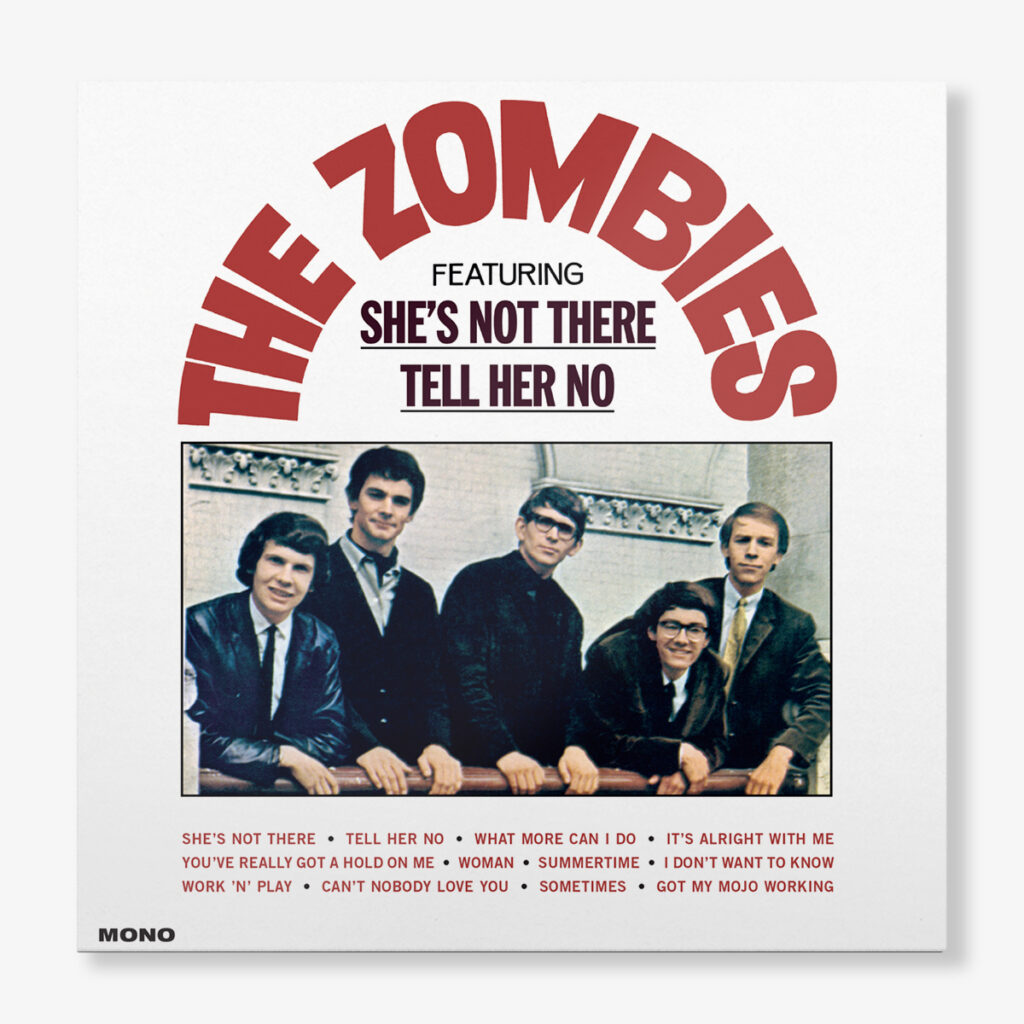

- The band’s eponymous first album

- A singles compilation that Varèse Sarabande released as The Zombies but is now called I Love You

- The aborted album of leftovers and posthumous recordings (compiled on the Zombies Heaven box set in 1997) titled R.I.P. by Varèse Sarabande in 2014.

In late 1978, the second issue of Trouser Press Collectors’ Magazine contained this lengthy feature on the Zombies. With the new reissues, it seemed like a timely thing to take down from the shelf, dust off and share.

By Peter Olafson

There’s no denying that the Zombies were one of the most tragic casualties of the British Invasion. Had they been handled differently, received stronger backing from their record company, started slower, been nudged away from jazz and pressed to record their second LP in mid-1965 anything could have happened. But that’s water under the bridge and probably irrelevant at this point.

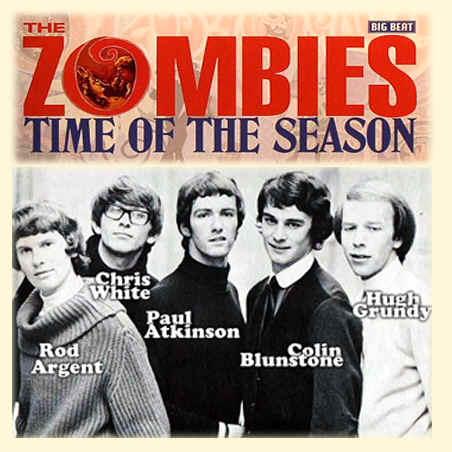

What is relevant is that the Zombies made music that was far ahead of their time; even now rock music in the main is just catching on to the kind of counterpoint and minor-chord composition that the Zombies were doing 13 years ago. They were a band that started out on top and slid slowly downhill, being ripped off by almost everyone they came into contact with along the way. (Paul Atkinson recently called their first producer, Ken Jones, “one of the two people we dealt with who didn’t rip us off.”) When their biggest hit of all, “Time of the Season,” finally happened, the group had been broken up for over a year and was too cynical about the business to get back together and capitalize on their success.

The Zombies made some of the most agreeable and innovative pop to come out of the 1960s. That’s pop with a capital “P” — with teeth, embedded in an utterly original sound. The Zombies could sing and play with rare beauty and rock with polish; their songs were compulsively melodic, their lyrics — rarely complicated —emotional and evocative. Girls, love, girls, love and love — that was the Zombie worldview, just like it was the Beatles’ until Revolver.

A four-track recorder and a one-track mind: plug in the Zombies and you couldn’t miss. Of course they did miss. Perhaps it was because they were too different; it was cold in the Beatles’ shadow on the minor-chord fringe of the British Invasion. And what kind of group was the Zombies, anyway? Two of them wore glasses! And who else subordinated the standard guitar-bass- drums lineup to feature keyboards? Like those classical guys, right? And jazz! Blech! And who else but Colin Blunstone sang like his heart was in his throat and delivered lines like “Well I am hurt / But I still love you” like he’d just plucked an arrow from his side and handed it back? Nobody. There were other great songwriters, other singers, other bands. But none of them was quite like the Zombies.

The band was originally composed of Rod Argent (keyboards), Paul Atkinson (guitar) and Hugh Grundy (drums). The three were attending the exclusive St. Albans Public School in the county of Hertfordshire, northwest of London, in early 1962, satisfying what small musical ambitions they had by playing one-off gigs at local pubs and dances on weekends. By mid-’62, they’d achieved a measure of success, and 17-year-old vocalist-guitarist Colin Blunstone and bassist Paul Arnold were brought in to flesh out the three-man-band’s limited sound. Arnold didn’t last long: he left late in the year to concentrate on his studies and was replaced by Chris White. The new-look quintet practiced more – often in a room above Chris White’s father’s store in the town of Markyate – and played more, graduating to colleges and rugby clubs, where they mixed a handful of Argent/White originals with R&B standards. But the band’s increasing popularity and powerful live performances promised little. Argent and Atkinson planned to attend university and White to a teacher-training college. Grundy and Blunstone had jobs lined up in the banking and insurance businesses. It appeared the Zombies would end when the five teens graduated St. Albans in June of 1964.

And the band would have broken up if Chris White hadn’t suggested entering the London Evening News‘ “Hert’s Beat” contest. The competition was designed to draw out local Hertfordshire talent – the winning group would record a demo to be pushed at major British record companies. So the Zombies, who had nothing to lose and everything to gain, rehearsed vigorously and, armed with a batch of new songs, auditioned in May.

They won on the strength of Rod Argent’s “She’s Not There” and were promptly grabbed up by Decca (UK). To no one’s surprise but their own, the Zombies had become professionals. Terry Arnold became their personal manager, the agent of the band’s schooldays became their roadie and Ken Jones their producer as Decca dumped them into a studio in mid-June to record their first single.

They almost made a disastrous mistake. Argent, a jazz fan, wanted to release a version of George Gershwin’s “Summertime.” And no doubt it was one of the band’s best: Colin’s breathy, too busy-to-be-bothered vocal was perfectly suited to the song’s lazy lyrics and tempo, Argent’s piano solo complex and arresting. Especially nice were the cool backing “ooo’s” that iced the mix, reminding the listener nowadays more than a little of the Kinks’ later “Waterloo Sunset.” But in the beat group days of 1964 it was utterly uncommercial; its release at this stage in the group’s career would probably have doomed the Zombies to an early grave. Decca, to its credit, persuaded the band to also record original material. “Summertime” went back into the vault, emerging only late in ’64 on the Zombies’ debut LP, and the band stayed in the studio, recording and releasing “She’s Not There” on July 18, the day Paul graduated from school.

“She’s Not There” is a tremendous record: clink-thud assembly-line drums and off-base jazz piano rolled into Colin’s wispy falsetto, backed by great harmonies and punctuated by one of Rod Argent’s best keyboard workouts. It was a well-considered trick: screwing brisk classical-jazz into the traditional beat framework. The single rocketed to number-one in America (where it was issued on Parrot) but only reached number-12 in England, where it was praised by George Harrison on Juke Box Jury and became the biggest hit of the band’s career. (The Zombies, paradoxically, never had a real commercial breakthrough in England.)

By September, “She’s Not There” was a worldwide hit, selling well over a million copies – mostly in America, where Parrot (a subsidiary of London Records known for lackluster promotion efforts and bizarre taste – they passed up the Beatles in ’62) turned it into a monster hit. The Zombies, the press stressed, were good, clean-cut boys — scholars all — and lots of shots were taken of them playing chess, posing with chimpanzees and generally being studious and intent – no art school drop-outs these lads. They certainly sounded rougher on the flipside, a superlative beat number called “You Make Me Feel Good” (“You Make Me Feel So Good” on some US pressings). This crisp Mersey pop-rocker had a vaguely Beatlish feel to the harmonies, a definitely dirtier caste to Colin’s vocal and a tense instrumental track that balanced Argent’s slow-rocking piano against Atkinson’s spare guitar work. More conventional than its great A-side, “You Make Me Feel Good” nevertheless showed the Zombies refusing to be pigeonholed.

As did the band’s second single, “Leave Me Be,” which as a result sank without a trace after its release in October. The “ultimate teen melodrama,” according to one critic (and all subsequent discographers), “Leave Me Be” was atmospheric, low-key pillow-rock that shifted with ease and moody beauty from its acoustic, folkish verses to the strong rock vocal and organ of its chorus. Colin had never been in better voice, the Zombies never so comfortable with their own versatility. But the band was again exploring territory into which its audience was reluctant to follow. A shame, too, because its flipside, Rod Argent’s “Woman,” was a model of grimy, whiny blues in the “Lost Woman” Yardbirds mold and representative of the Zombies’ 1962-3 stage act.

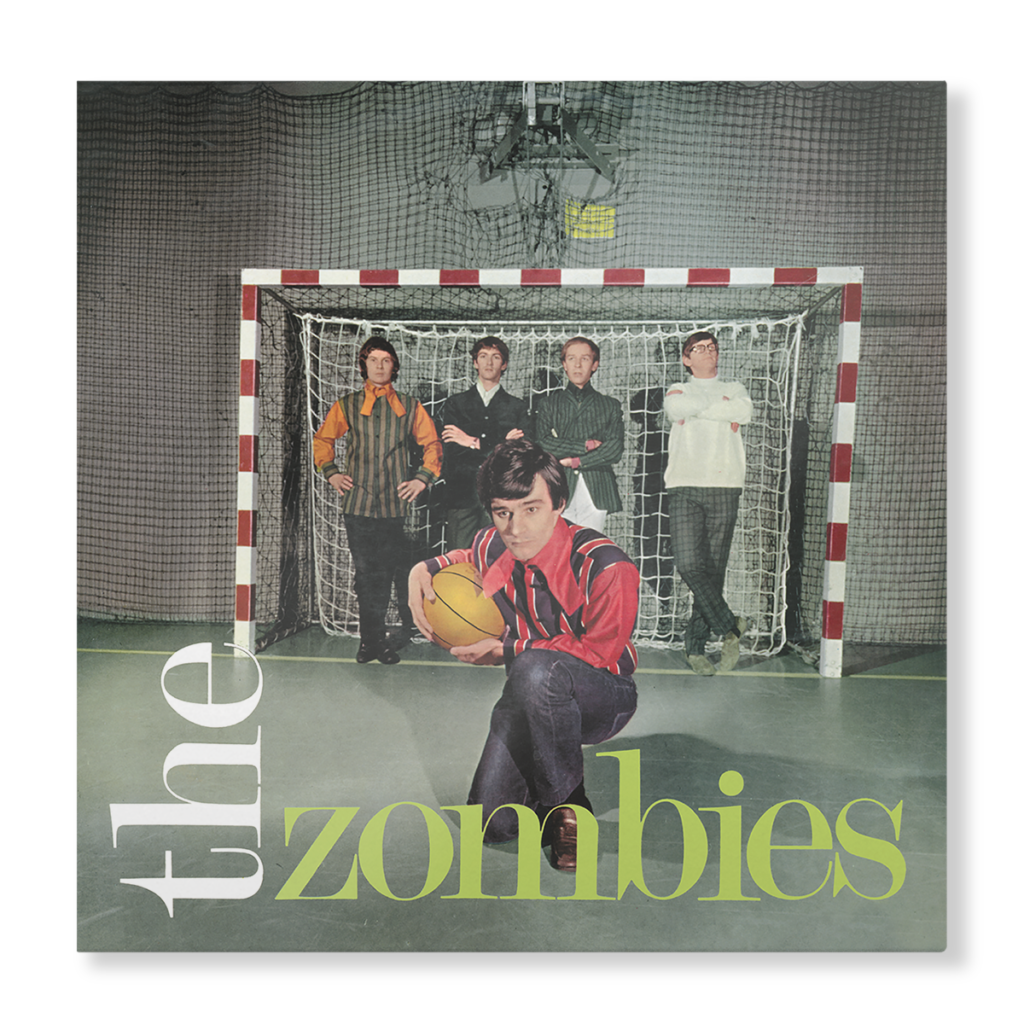

The failure of “Leave Me Be” and the approach of the Christmas season led Decca to send over LP tapes in late fall. Parrot released The Zombies in early December, presumably to cash in on the group’s huge American popularity before “She’s Not There” faded to a pleasant memory. Decca apparently didn’t think Britain was ripe for a Zombies album and held it back until March. The US album was pop dynamite – harder than the intelligent but relatively lightweight pop the band had hit with, steeply angled toward crowd-pleasing blues and soul chestnuts and Argent’s attempts to imitate them. Filler? Uh-uh; the Zombies made those covers their personal property and steamed and thumped through their rewrites of those songs with such assurance and, well, spunk, that you had to go back and check the credits to see whose songs you were hearing. Case in point: no one –but no one — could challenge the Beatles’ stunning interpretation of Smokey Robinson’s “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me.” So the Zombies didn’t –they took it apart and put it back together again. Colin barely sings lead at all; his vocal is mixed back into the group’s to achieve an effect somewhere between a campfire sing-along and a barbershop quartet, and grafted the song to Sam Cooke’s “Bring It on Home to Me.” The sound is trebly and knotted up, the instrumentation spare. The song almost sounds unfinished, but it’s still great. And if any one’s not convinced these guys could rock, may I direct the court’s attention to the unrestrained rock’n’roll dynamics of “I Got My Mojo Working”? Or to the stupendous bluesy lead vocals on “Can’t Nobody Love You”? Or to the skifflish instrumental “Work ‘n’ ‘Play”? Or to the full-scale pop treatment they lavish on Argent’s “It’s Alright With Me” with its great shift into lazy blue jazz, rave-up screams and elegant, rocking solos? This was biting, hot-cored lightning-red rock’n’roll — by the Zombies, of all people, and it couldn’t have come as a bigger or more delightful surprise!

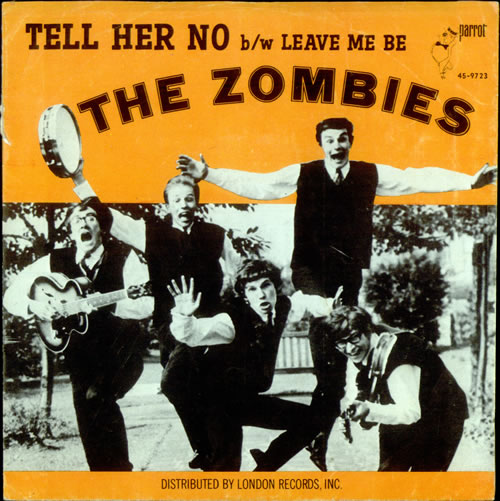

Better still was the gorgeous melodic pop the Zombies had shown they were capable of creating on their first single. “Tell Her No” was stylistically similar to “She’s Not There” — bouncy as hell, with another neat drum-keyboard intro, great beat, great vocal, simple chorus: “Tell her no no no / No no no….” Well, it doesn’t look great in print… The single skidded onto the UK charts at number-30, and the Zombies had another worldwide hit. There should have been others. Chris White’s folk-rocky “I Don’t Want to Know” may have been the best song on the album; its melody echoes Lennon/ McCartney’s “Bad to Me,” while its spangled guitar intro and solo recalls Buddy Holly’s “Words of Love.” Add on exquisitely accented chorus vocal (“I don’t want [pause] to knaaoow”) and Hugh Grundy’s resonant, propulsive drumming and you’ve got an unforgettable cut. “What More Can I Do” opens with funeral organ (hats off, heads down) and unexpectedly bursts into a monumentally attractive descending chord progression with loads of rapid-fire vocals and drums. “Sometimes” starts a cappella, but rips into the body of the song in the best “Shout!” tradition. So much for predictability; The Zombies was a masterful, incredible (though much maligned) album that caught the very best the early group had to offer on vinyl. And it sold respectably in what was essentially a singles market. The Zombies were at the zenith of their drawing power and still growing as musicians. What would they do next?

Plans called for them to tour America with the Nashville Teens in the winter of 1964-65. But nervous US immigration officials, taking the British Invasion literally, refused to issue the barbered, grinning Zombies visas. So they’d put out a great LP, and “Tell Her No” was crackling from transistor radios from coast to coast, but the band couldn’t tour to promote it! The powers-that-be fluttered and fumed, agents “negotiated,” and the Immigration Service eventually decided it wouldn’t hurt (much) to let one more British band visit the States. So the Zombies were in; they did Murray the K’s Christmas show at the Brooklyn Fox (where Atkinson had his clothes ripped off by admiring fans while trying to get a sandwich) for ten days, appeared on the first Hullabaloo TV show, but were not allowed to continue on past New York. Returning to Britain early in 1965, they did the circuit of clubs, ballrooms and theaters and put in appearances on Top of the Pops and Ready Steady Go.

Decca decided the UK was prepared to digest a Zombies LP and finally released one, titled Begin Here, in March. It became quite rare due to the inclusion of five previously unreleased tracks, most of which are pretty good. “Roadrunner” is a competent blues – bassier and more guitar-oriented than most of their material—but nothing to rave about. “Sticks’n’Stones” is notable for Colin’s unrestrained vocal and some terrific drumming from Grundy. But the three other cuts really stand out; “The Way I Feel Inside” and “Kind of Girl” are wonderful, light pop: first-rate harmonies matched with unforgettable hooks. “Kind of Girl” has a middle-eight that sounds like something from Beatles for Sale played sideways.

But both pale next to “I Can’t Make Up My Mind,” another piece of classic Zombie-pop in the same league with “I Don’t Want to Know.” A great guitar hook, hard-edge background vocals and a sinister feel the dapper Zombies hadn’t previously looked into put “Mind” well beyond anything the group had produced thus far. It wasn’t just subtle, socko radio-pop, but a signal that the band’s songwriters were growing more skillful and adventurous, capable of musical creations beyond those suggested by their early models.

But as “Tell Her No” slipped off the charts the Zombies had already begun to slide commercially, if not artistically. Though they toured the US three times – once with Dick Clark’s Caravan of Stars – and hopped around the globe to wherever fans beckoned (to the Philippines, for example, where the band arrived to find they had five singles in the Top 10, played two shows a night for a week in an 18,000-seater and were royally screwed when it came to being paid for their services). Decca/Parrot’s “we made-you-we-can-break-you” merchandising gambits and half-hearted promotion poisoned the chances of a band that, handled properly, might have achieved something quite spectacular.

And sometimes the band cut their own throats. The follow-up to “Tell Her No” was another Argent composition, “She’s Coming Home,” backed by Chris White’s “I Must Move.” Released in April, the single was a minor chart hit in the US; a strong, commercial number with Spectorian production, huge piano chords and strange, abrupt changes. “I Must Move” is just another one of those off-the-wall pieces of progressive pop that doesn’t even sound like the Zombies until they start singing – a fascinating Eastern-influenced intro of repeated guitar chords leads into a lovely Merseyesque ballad highlighting dense, lush harmonies a little in the style of “This Boy.” It should have been the A-side, but as it stood, “I Must Move” was just another example of the ongoing Zombie dilemma of what was commercial and what wasn’t.

Their next US release, “I Want You Back Again,” was good James Bond-ish jazz, its flip “I Remember When I Loved Her” superb haunting folk-rock containing not only a pretty guitar part (and Argent’s most concise and moving solo) but a small work of genius in its tortuous instrumental climaxes and Colin’s pathetic, passionate vocal. It’s the kind of song that can bring tears to the eyes – no mean feat. Fortunately, they still had an audience by mid-’65 and didn’t have to sink into the UK cabaret circuit; there was always someone somewhere that wanted to see them. But as Colin put it, they also knew the “sparkle” was gone.

Sparkle or no sparkle, in the summer of 1965 the Zombies entered a period of unparalleled creativity. They couldn’t hit a sour note, make a wrong move. And they got a proper reward, right? Nope. A big fat zero. “Whenever You’re Ready” kicked it off in August. Forget “I Don’t Know” and “I Must Move”— this is quintessential, explosive Merseybeat, the carbonated extract of what the pre-Odessey and Oracle Zombies were capable of. Who’d have guessed it: it starts with just Colin’s moody vocal, hi-hat and subdued piano and guitar. And then, out of nowhere, the song blasts off like the Beatles in overdrive – to an impossibly attractive chorus and glorious, bouncy bridge. It’s no wonder the gentle “I Love You” was placed on the flip – you need to gear down after coming through such a rock’n’roll wringer. And the flip (later a minor hit for an American band called People) was very pleasant; it caroms between acoustic guitar strum and bass-drum beat. On first impression, it’s just a banal love song, but the key line isn’t “I love you” but “And I don’t know what to say.” Listen to Colin’s charged vocal, to the slightly on-edge arrangement, to the barely perceptible pulse in the bottom of the sound and you’ll find it has less to do with love than with the singer’s inability to express it. The irony is that he is expressing it in “I Love You.”

In November, the Zombies issued a strange single: “Is This the Dream” b/w “Don’t Go Away.” “Dream” was distinctly less melodic and more hard-rocking than recent Zombie efforts and seemed like a return to the rugged, elemental pop of the band’s first LP. The band rocks and yells “Hey, hey, hey!” while Colin nasally bulls his way through the lyrics. Grundy drums up a storm, White’s bass (usually inaudible) pulsates and Argent delivers an unusual solo. It was recorded live in the studio and sounds like something generated from a jam session. If it was a step sideways and somewhat unadventurous, it was also inoffensive and fairly exciting rock’n’roll with a good hook. “Don’t Go Away,” on the other hand, is still another of those “should have-been-the-A-side” B-sides: excellent folk-pop, extremely complicated melodically, containing another awesome Blunstone vocal. Parts of the song have an almost Byrds-like quality, not blatant, just there. The Zombies weren’t operating in the vacuum of their artistic successes but learning, adapting and developing.

And recording. By late 1965 it was apparent that the group was sitting on an unreleased batch of completed tracks and that an album of new Zombie material was a definite possibility. The announcement that the band would appear in the film Bunny Lake Is Missing lent further support to speculation about a Zombie…er, revival.

A film soundtrack LP was released, containing unblemished versions of the three songs they performed in the movie and lots of undistinguished instrumental music (not by the Zombies). Those three cuts (later included on UK Decca’s World of the Zombies compilation) are all superb: “Remember You” is speeded-up jazz after “Summertime” but really more pop – simple, repetitive, uptempo and devastatingly bouncy. “Just Out of Reach” is a rare Blunstone composition that, echoing the work of cohorts Argent and White, is peculiar all on its own. The lyrics don’t quite meet the beat, the drums are the lead instrument and the song has an accidental-on-purpose drum ending, obviously intended to sound spontaneous, just sloppy enough to reveal that the song doesn’t have a proper ending. The chorus, however, has the kick of a mule. Chris White’s “Nothing’s Changed” is neat, neat, neat – no organ or piano. Deadly simple but deadly effective acoustic guitar solo. Heart-rending chorus. File this with “I Don’t Want to Know” and “I Must Move” as prime examples of Chris’ composing genius.

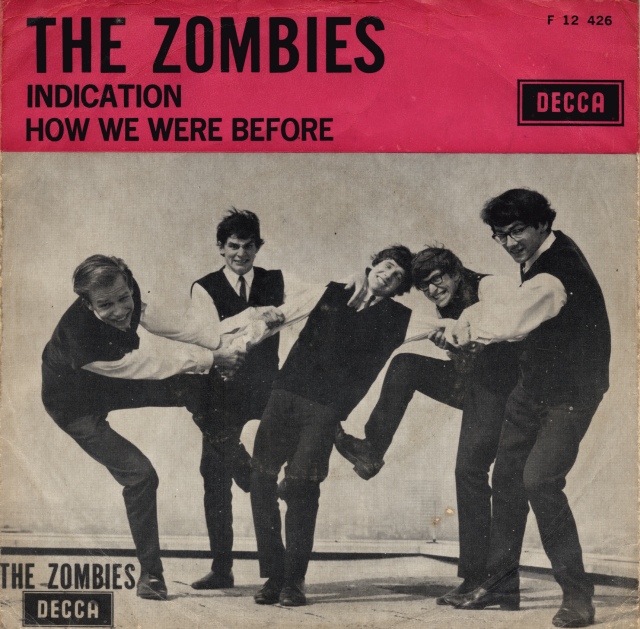

“Remember You” and “Just Out of Reach” were released as a single in January of 1966 and flopped. Not so “Indication,” The Zombies’ ’66 summer single, which was a substantial regional hit in the US. Virtually bristling with hooks, “Indication” jams every trick in the Zombies’ book into two minutes: a beautiful organ intro and harpsichord ending, two stunning a cappella breaks with strong harmonies and babbling organ. A good melody too – the “indication”/“sensation” rhymes rolled nicely in the mouth. It also features Rickenbacker guitar, pumping bass and an extended instrumental work-out at the end. The Zombies go psychedelic: ghostly background vocals, weaving instrumentation and a heavy descending melody-line turn the happy “Indication” into a Zombie dirge. Turn the record over and you get the pretty calypso of “How We Were Before.”

The Zombies’ sound was growing by leaps and bounds; they were experimenting with new instruments and absorbing new influences. If Decca had sat them down and budgeted an LP, there’s no telling what they might have come up with. But Decca appeared to remember the Zombies as the band that had failed to produce a follow-up hit to “She’s Coming Home.” Plainly it would have taken another “Tell Her No” to impress the label, and the Zombies were by now far too sophisticated and forward-looking to take what, for another band in their position, would have been an obvious step.

The last official Decca Zombies single, “Gotta Get a Hold of Myself” b/w “The Way I Feel Inside,” was issued early in the fall of 1966, and seemed to indicate the group’s uneasiness about their label and their future. Only one of the songs was new. “Inside” came from the two-year-old Begin Here album, while “Myself” – despite promising lyrics — is more suited to Tony Newley than the Zombies. The brassy track is a heavily-produced, over-arranged upbeat ballad. As the saying goes, MOR is less. Rod Argent’s organ sounds like horns; White’s bass-playing is excellent, but the real Zombies surface too rarely.

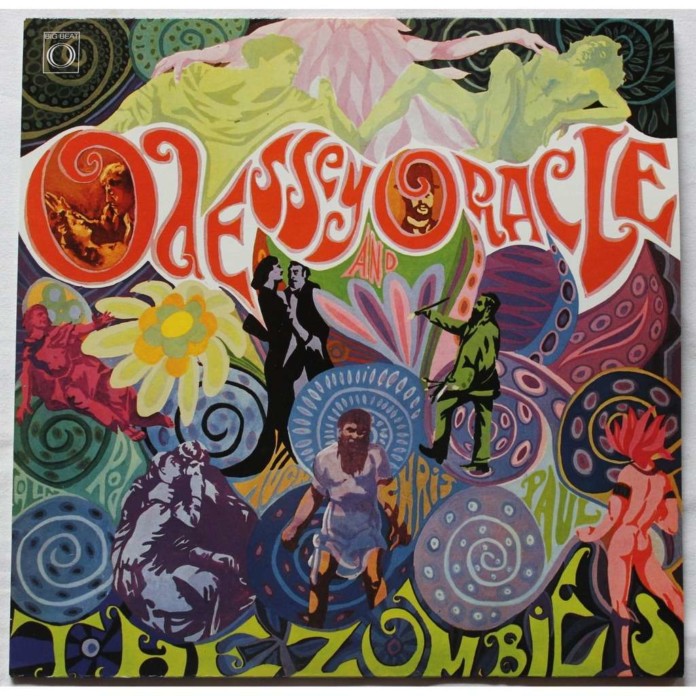

They may not have cared a whole lot by this time. A three-year contract with Decca would run out early in 1967, and the label wasn’t begging them to renew it. The group knew that they weren’t wanted and left. CBS signed them, gave them some money (Rod and Chris chipping in some more from their songwriting royalties) and amid talk of a break-up (actually, they had decided to split before signing with CBS, they just wanted to do one more LP), in June 1967, the Zombies went into the Abbey Road Studios recently vacated by the Beatles and cut what would become the bizarrely misspelled Odessey and Oracle, their second and final LP.

Decca dug into their vaults and exhumed two tracks the Zombies had never intended for commercial release. “Going Out of My Head” is a passable rendition of the Dionne Warwick hit. Probably from the same sessions as “Gotta Get a Hold of Myself,” and certainly recorded with the same audience in mind, it sounds like the Association. But the flip, probably from the spring of ’66, was solid gold. And weird: “She Does Everything for Me” is incredibly atypical for the Zombies. It starts with an acidy, Eastern guitar intro (partly borrowed from “Paint It Black”), has handclaps, great, boastful — no, nasty — lyrics, and strung-out backing vocals. What’s even odder is that under this purple haze lurks an unassuming little Zombies song. “She Does Everything for Me” wasn’t just a classic, but a landmark the Zombies would never touch again.

The Zombies worked through the summer of 1967 to complete Odessey and Oracle. It was a masterstroke – one of the best pop LPs of the late 1960s that shows the Zombies fully matured and at the peak of their considerable talents. Colin’s voice is at its breathless best, the group’s playing sharply defined and economical, Argent and White’s songwriting clever and varied, the production barely ’60s production at all and at once lush and uncluttered. “Care of Cell 44″ opens the album – a link to the Zombies’ new music, with McCartneyesque bass and a subtly sophisticated melody that sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday. “A Rose for Emily” is probably the simplest arrangement the Zombies ever performed: just Colin’s gorgeous vocal and Rod’s piano. “Maybe After He’s Gone” is another dose of the Zombies’ brand of folk with beautifully eerie lyrics. “Beechwood Park” has similarly eerie lyrics, church organ, Leslied guitar and soaring harmonies. “Brief Candles” features Chris White’s prominent bass and remarkable harmonies, with a synthesizer used sparely and majestically. “Hung Up on a Dream” again emulates Phil Spector, with plenty of echo guitars, vocals and drums and Paul Atkinson’s best guitar solo ever.

Side two is just as good. White’s “Changes” sounds like a choir – but in what kind of church? As much of the album does, the song shows strong classical leanings. “I Want Her She Wants Me” – later covered by the Mindbenders – is the lightest thing on the album, cream-puff pop that could have been recorded by the Cyrkle or the Archies.

Recorded only a few months after the Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper’s in the same studio with the same engineer, the Zombies album begs comparison to it. “This Will Be Our Year” sounds like the Beatles: the “Penny Lane” trumpet solo and some of the backing vocals have a Magical Mystery Tour feel. On White’s “Butcher’s Tale (Western Front 1914)” nightmarish studio effects lead into a 12th century melody and a lyric that conjures up Breughel paintings. “Friends of Mine” is riveting pop, as, of course, is “Time of the Season”; basically a ’64 Zombie song slowed and equipped with a few Spike Jones vocal tricks and a West Side Story ambience. Add Colin’s vocals and the great ’60s organ solo and what have you got? Musically a song (and an album) that, easily dissected, were far greater than the sum of their parts. Commercially, in late 1967, though, it didn’t amount to much.

But early in 1969, “Time of the Season,” released by Date almost as an afterthought (and recorded by the Zombies as an afterthought, as well), snuck into the lower reaches of the charts and eventually bulldozed its way to the top, selling over a million copies. The Zombies had their third worldwide hit, but by then as a group they were long gone. In spite of offers of up to £20,000 for a single Zombies concert, Argent demurred as he concentrated on putting together his namesake band without Blunstone. (If the real ex-Zombies didn’t have the time or the interest to perform together again, certain unscrupulous Midwestern groups were willing to pretend that they did. Charging as much as $7,000 a night, they raked in the “Season” concert harvest.)

CBS/Date saw dollar signs, too, and made a few limp attempts to follow up on the Zombies’ belated success. In the spring of 1969, Argent’s new band went into the studio to record new “Zombies” tracks to combine with the handful of ‘65 outtakes CBS owned. The planned album never got past the acetate stage (only to be released many years later), but four of the proposed tracks came out as singles that year. The first was “Imagine the Swan” / “Conversation Off Floral Street.” Composed by Argent and White, it sounds like a discarded Odessey and Oracle number. It’s not really the Zombies, but it’s not bad: Rod sings a lot like Colin here (not too surprising, since he’d almost sung lead on “Time of the Season” and would do an uncanny impersonation of Colin’s style in later Argent stage performances). The B-side is a good-timey instrumental and not Zombie-like at all. But the single flopped badly. As the lean months in 1965-66 had shown before, the Zombies’ name wasn’t by itself enough to sell records.

In June, CBS/Date scraped bottom again and found gold. “If It Don’t Work Out,” recorded as a demo for Dusty Springfield (the song is on her This Is Dusty LP), is a gem, a snappy rocker tarted up with strings, excellent drumming and a super “Ticket to Ride”-styled hook. White’s “I Know She Will” is more delicate and even better, containing a great bridge where surging strings, jangly guitar and thick harmonies interlock and flow together like one instrument. It, too, bombed and CBS’s vaults thereafter stayed closed. The Zombies, dead already as a reality, died again as even an idea.

Or did they? London, Parrot’s US parent, rushed out The Early Days in 1969, a collection of single sides that had never appeared on LP. Decca did the same with World of the Zombies and Rock Roots: The Zombies, the result being that anyone who wanted every song the Zombies ever released could get most of them for about $20. (London recently deleted Early Days, unfortunate as it contains “I Want You Back Again,” “I Must Move” and “Don’t Go Away,” all very difficult to find on 45.)

Epic’s two-LP repackage, Time of the Zombies, is the definitive compilation. It contains the best available pressing of Odessey and Oracle, a few singles (like “She’s Coming Home” and “Imagine the Swan”) not included on prior compilations, both sides of the last 45 and no less than five unreleased tracks — not the Zombies, but early tapes of Argent (the band) cleaned up and overdubbed.

The careers of the ex-Zombies are interesting. Guitarist Atkinson and drummer Grundy became A&R men for CBS. Chris White, content to be Argent’s righthand man in the studio, stayed in the shadows (as he had as a Zombie). Colin put out a couple of singles as Neil MacArthur on Deram (one, a remake of “She’s Not There,” was a minor hit in Britain), put in a brief stint as an insurance salesman, returned in 1971 to make the first of a series of albums of soft, string-laden Zombie-ish pop-rock, and then signed to Elton John’s Rocket Records. Argent’s band produced one excellent and one good pop record and a whole batch of mediocre pomp rock LPs, as Rod donned medallions, grew his hair longer and relegated an ever-greater share of the songwriting to guitarist Russ Ballard. Tired of the pompous direction Argent was taking the band in, Ballard left in 1974, to be replaced by John Grimaldi and John Verity. When Grimaldi quit early in 1976 the band finally split up and Argent pretty much disappeared, at least until a few months ago, when British MCA issued an intriguing synthesizer single (“Gymnopedies No. 1” b/w “Light Fantastic”) under his name. He’s recently opened a keyboard shop and appeared on Andrew Lloyd Weber’s Variations and Who Are You.

From time to time the original Zombies have talked about getting back together, but they’ve never quite made it to the final stage. The closest they got was at the end of 1977, when the band — with guitarist Tim Renwick standing in for Atkinson — re-recorded a few old hits for an English K-Tel compilation.