In the early days of Trouser Press Collectors’ Magazine, we interviewed several British label founders, including Andrew Loog Oldham (Immediate) and Tony Stratton-Smith (Charisma). It still seems rather amazing that we got to interview down-to-earth billionaire Richard Branson and his Virgin Records manager, Simon Draper, at length in the summer of 1979 at the company’s West Village office on the occasion of their new American imprint. This article originally appeared in TPCM 7.

Interview with Richard Branson and Simon Draper of Virgin Records by Ira Robbins and Dave Schulps

Had you wanted to sign the Sex Pistols before their deals with EMI and A&M?

Richard Branson: When EMI signed them, we’d shown interest but hadn’t really gone after them. We then saw another concert and heard the “Anarchy in the UK” 45, and I rang up Leslie Hill, the managing director of EMI, and left word with his secretary that if he’d like to get rid of this embarrassment, would he give me a ring? The next night the Pistols were on the Bill Grundy show, and the following day I got a call from Leslie Hill to arrange a meeting.

I went over to EMI and he showed me the Pistols’ contract and asked if I’d read it there, because they needed to make a quick decision. I read it over and agreed to take over the contract from EMI. Then McLaren came in, and we basically came to a deal. The next day, A&M announced that they were going to sign them, which they did, but a few days later, when A&M fired the group, we had a call asking if we’d like to sign them again.

But you really did want to sign the group by then?

Simon Draper: In fact, we couldn’t have planned it any better. It was great to be the third in line. One imagines they had worked off a lot of steam by the time they settled down with Virgin…

RB: Actually there weren’t many people left they could go to by then.

SD: I read a recent interview with Malcolm in which he said that the only thing he found was that he couldn’t fight against us in the same way as with the other labels. He liked to get that polarization with the record company.

Were the Pistols the first real new wave group signed by Virgin?

SD: We signed the Motors before, although it’s questionable whether they’re really new wave, and we had really tried to sign the Boomtown Rats at around the same time as we signed the Pistols. We spent a lot of energy trying to sign the Rats.

Was Virgin’s interest in new wave a conscious change of direction?

SD: We’re an English label, and what’s happening in England is what we’re concerned with, and new wave was overwhelmingly what was happening, from the end of 1976. But at the same time, it happened to coincide with a period that we were going through. A lot of the groups that had originally formed the label’s roster weren’t getting anywhere: Can, Wigwam, Henry Cow. There was a lot of belief in them in the company, but we weren’t actually selling any records. We had a meeting where we sat down with all of the main members of the staff — about 16 people — and went through the roster, and we more or less voted on them. We terminated quite a few contracts as a result of that meeting. We set about trying to make a new start, which just happened to coincide with what was going on in music at the time.

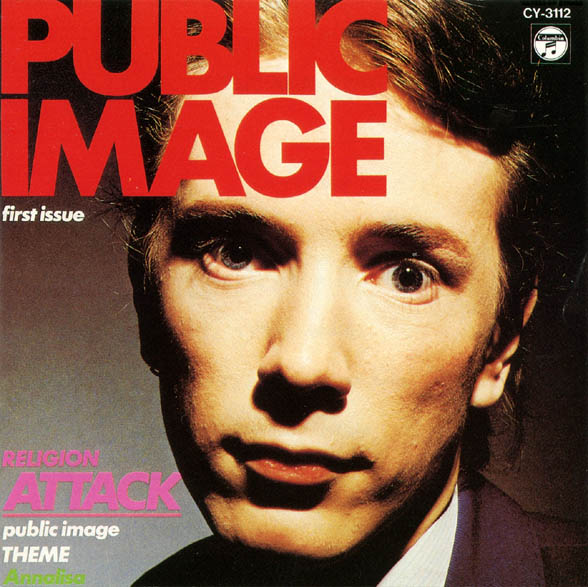

How is Virgin’s relationship with Public Image Ltd?

SD: It’s a pretty unique relationship. Lydon does things the way he wants them done and he has the most extraordinarily good ideas about artwork and such. They were very difficult in the beginning, but it’s much better dealing with them now.

Did PIL sign to Virgin because of the Pistols’ contract?

RB: To an extent. We pay them as much as we pay the Pistols.

Could they have signed to another label?

RB: Not really. We had an option on the individual members of the group.

Does the PIL contract allow them to do things other bands on the label can’t?

SD: Not really. We work with the groups the way they want to work.

RB: Our attitude’s changed. Originally, when the label began, we were going to give artists total freedom — that was the whole idea. We’ve learned that, to an extent, if you’re investing an awful lot of money you have to use your own experience. Groups sign with you because they see the results you’ve gotten — they know if they sign with us we’re not going to fuck them up.

SD: Groups in the beginning used to do what they wanted, and we never really questioned them, but now it’s cooperative. Although we’re quite aggressive, we would never force a band to do something or use artwork or anything that they don’t want to use. But we’ll certainly make our opinion clear.

RB: In the early days, bands would just record the music and we’d put the record out that would be that. But now, if a band turns in a tape that we don’t feel is ace, we’ll ask them to work on it.

SD: There’s still shades. PIL’s a good example. Their contract is structured in such a way that they record on their own. They’re interested in what we think, but it doesn’t actually affect things very much. I’m glad to say that the new stuff they’ve recorded is very good. It’s pretty uncompromising. They record a bit like Can — they go into the studio and play for 25 minutes, and then pick out the bit they like. They’re not actually composing songs. In retrospect, you can see how influential Steve Jones was in the Pistols’ sound.

What is Virgin’s attitude towards colored vinyl, picture discs and the like?

SD: We found that people are very oriented toward the look of things, and if we want to break someone — get a new single in the charts — we should give our bands an edge.

RB: The kids do like singles in picture bags. I think part of the reason why singles are doing so well as compared to albums in England is because of picture bags.

SD: I believe that packaging is important — you have to make it all hang together. Why should the packaging from stop at the record? It becomes crass at the point where it’s obviously gimmicky and hype-y. You get a thing like the Members’ single (“Sound of the Suburbs”), which probably wouldn’t have gone straight on the radio playlists — probably wouldn’t have been particularly well-received by radio people. So you have to get in the charts – you’ve got to actually force those people’s hands and doing a package that looked extraordinary [clear vinyl with the label info scratched in the plastic in a clear plastic bag] got it in at 37 immediately.

RB: In England you’re relying on about two or three things. If you get into the Top 50, you might get on Top of the Pops. If you get on Top of the Pops, you might persuade the radio to play it. They won’t experiment, so basically any trick goes to get it played.

Do you find it interesting that a song by the Members, “Solitary Confinement,” went nowhere as a Stiff one-off 45 but is now getting great response as a track on their Virgin album?

RB: Well, Stiff didn’t really believe in the Members. I think that’s what it really comes down to.

Does it surprise you that things have changed enough to allow a group like the Skids to succeed in the singles charts?

SD: John Peel was the guy who got us to sign the Skids — he was playing them on his British radio program and really, really pushing them. They went out on the Stranglers tour, and every time people saw them live, they converted a lot of kids. When their first single came out no one in the press particularly liked them, but it sold 35,000 copies! We knew something was happening. The second single (“’Sweet Suburbia”) sold 40,000, so when we released “Into the Valley” it didn’t surprise us at all that it was a big hit. Now the Skids draw about 3,000 people to gigs — it’s incredible.

Could Virgin make anybody it signs a success?

RB: We only sign artists that most of the people in the company believe in. If you believe in something, you can go out and make it happen. Of the last ten artists we’ve signed, we’ve broken nine of them.

SD: If you sign a group that has the natural ingredients in the first place —- most of the bands we sign have already been out on the road — the Ruts have done a tremendous amount of work, same with the Members and the Skids. We know how to make the best of the circumstances. We’re in a particularly good position to do it in England right now. We’ve got our own sales force that only sells our stuff and we’ve got a very good relationship with the shops and our marketing’s very strong.

Are you self-distributed in England?

SD: No, CBS do all the boring stuff of actually shipping the records out. That’s really all they do for us besides manufacturing.

How do you feel about Virgin’s future in the States?

SD: When we were distributed by Epic, an album that sold 30,000 was as insignificant to them as if it sold five, as far as they’re concerned, because they’re always going for the big score. That’s part of what we’re trying to do, which is actually sell 30,000 albums, because that’s worthwhile from our point of view. There’s enough interest in America for these bands to tour here because the clubs can offer a reasonable amount of money. With cheap flights, there’s enough income from the clubs to cover the expenses of a tour. When Magazine played in New York, they got $2,000 a night, which is as much as they can make in England. I think the problem with the American record industry is that it’s too monolithic — it’s all or nothing. We’re willing to try and build something here.

How are the Virgin Record stores related to the label besides common ownership?

RB: Simon used to be the buyer for the stores. We began the stores nine years ago. That’s where we came from.

SD: The stores have changed very radically since the beginning—they’ve developed their own thing.

RB: We’ve opened stores in every major town, so that when we put a group on tour we’ve got that backup support. It’s the biggest chain — the most influential stores in England. We’ve just opened the largest record store in Europe — 60,000 square feet on Oxford Street in London.

Virgin also owns a rock club, the Venue…

RB: Late night entertainment in London is obviously duff, and for years we’ve been trying to find a place. We had to get a license to stay open till three in the morning, and we had to find a place where we didn’t have neighbor problems… There were so many problems — every time we found a place we got stopped for some reason. But we finally sorted it all out.

What areas are left for Virgin to get involved with?

SD: We’re getting into books, but the more we find out about the field, the more careful we’re getting. There’s a guy who’s come to us with a proposal for a Virgin Books company, which is very exciting. He’s a science fiction writer, Maxim Jakubowski, which is of interest to me, but I don’t think we can make much money. What we’re interested in is doing picture books, documentary books on a whole range of things, largely rock’n’roll-oriented. We’re also going into films now, which is an obvious extension of books.

Speaking of films, will Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle ever be released? Does it actually exist or has it been a long-term hoax?

RB: It exists, and will be released before the end of the summer, but whether or not in America we don’t know yet. We’re also finishing up a space film. Our basic idea is to make movies that will help our artists. Also, on the movie side, we’ve bought a cinema in London, but we’re pursuing that in a slow manner. We’re planning a bunch of low-budget movies.

SD: The thing about books that interests me — and I didn’t really know this — is that most writers are contracted to publishers on a book-by-book basis. So we could theoretically go to John Fowles and say, “We’d like to do your next book…”

RB: The other thing is the most stuffy set of people run the publishing world in England.

SD: The biggest mistake you can make is to be dilettantish, to dabble, so we’re trying to really enter publishing properly.

Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells album was Virgin’s first release and your first hit. How long had the enterprise been in existence?

SD: The label took about eight months to set up; the stores had been going for two years. In May ’73 we released Faust Tapes, Gong, Manor Live (which is best forgotten) and Tubular Bells.

Has Virgin had any major failures?

RB: Not really, except the clothes shops. We had some empty space in some of the record stores and we put in some clothes…apart from that, we’ve basically managed to do well.

Are you going to be signing bands in America?

RB: We’ve already got this band called Shooting Stars.

SD: I think we have to hold off for a while before been out plunging into American bands, but we will definitely…

RB: We just signed a band from Toronto: Martha and the Muffins.

SD: We’ve formed a new subsidiary label of Virgin which shares our sales force and manufacturing facilities but can operate as a very small unit. They’ve signed Martha and the Muffins as well as the Rezillos. Fay Fife and Eugene Reynolds have reformed the band with Eugene’s brother on drums and two other girls.

What was the real story of your signing Devo outside of the U.S., and Warner Brothers getting them for America?

RB: Warners were on the verge of signing them when we moved in pretty snappily. The day before Warners’ signing party — in fact, they’d already announced that they had signed Devo — we signed them for the world. Obviously, Warners were really pissed off. They got all their heavy lawyers in London and they flew over some lawyers from LA and they took us to court. The case went on for a few days, and it looked as though we were winning, and then on the last day of the case their lawyer got up and tried to enjoin us from putting out the record, using a precedent that involved Bette Davis. It turned out that the judge who ruled on that case was my grandfather! They got the injunction, so we agreed they could have the group in the States.

What did you offer Devo that made them jump ship at the last moment?

SD: They were always very unhappy about Warners. It’s a very complicated story, but they were being represented by a lawyer who was also representing Bowie, and they discovered that the deal with Warners was tied in to a deal with Bowie. They never wanted to sign with Warners for the world — we’d been talking to them for months. They didn’t mind particularly going with Warners for the States.

You mean Devo was getting pushed around?

RB: They were new to the record business..

SD: Jerry Casale is learning more about the business. They had willingly taken on the business. Jerry virtually manages the group.

RB: They were very suspicious, very astute, very careful, but they fell into traps every step of the way.

What brought you back to Atlantic?

RB: There’s people in the company we like and who like what we’re doing. Also we wanted a label based in New York. There were a lot of labels we didn’t want to go with. It’s a gut feeling.

SD: You look at track records in how they promote their artists. We had experience with MCA, because they put out a Tangerine Dream album, Sorcerer, and we didn’t want to sign with them. If you’re reasonably successful you can afford the luxury of working with people you like.

Do you think there’s a market for reggae in America?

RB: For individual artists.

SD: It’s a strange situation — the biggest market for reggae is the Third World and France. It’s very hip in Paris right now. Unfortunately it’s very hard to put reggae artists on tour, because all the Jamaican session musicians want so much money that it’s too expensive in many cases. They can do so much work at home that they don’t care to go to Europe or America unless they get paid a huge amount.

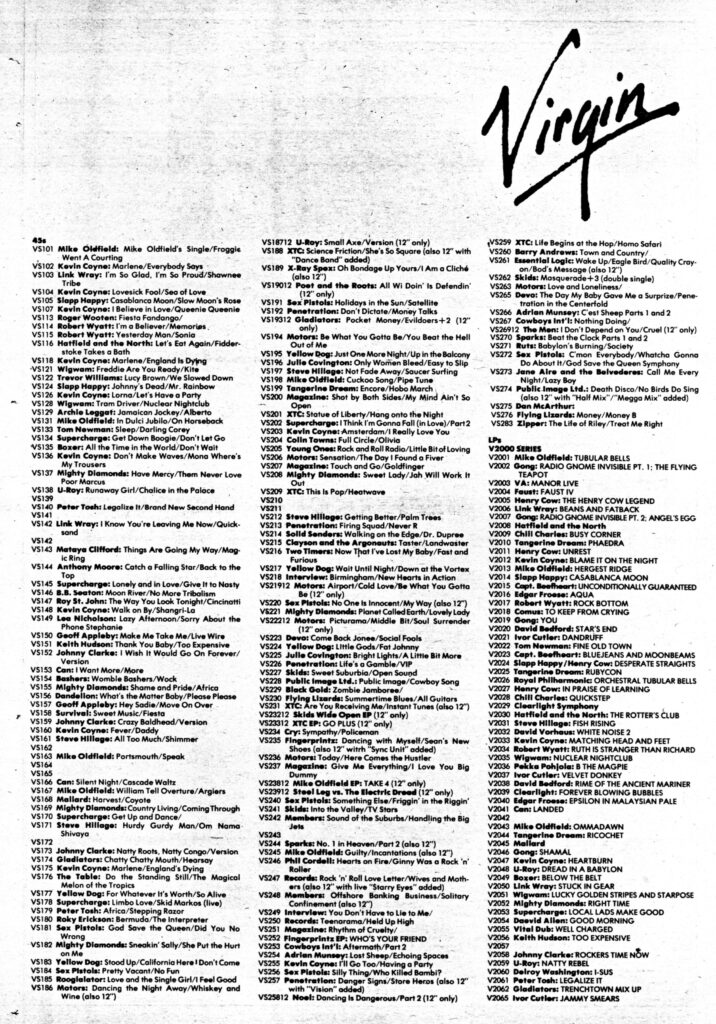

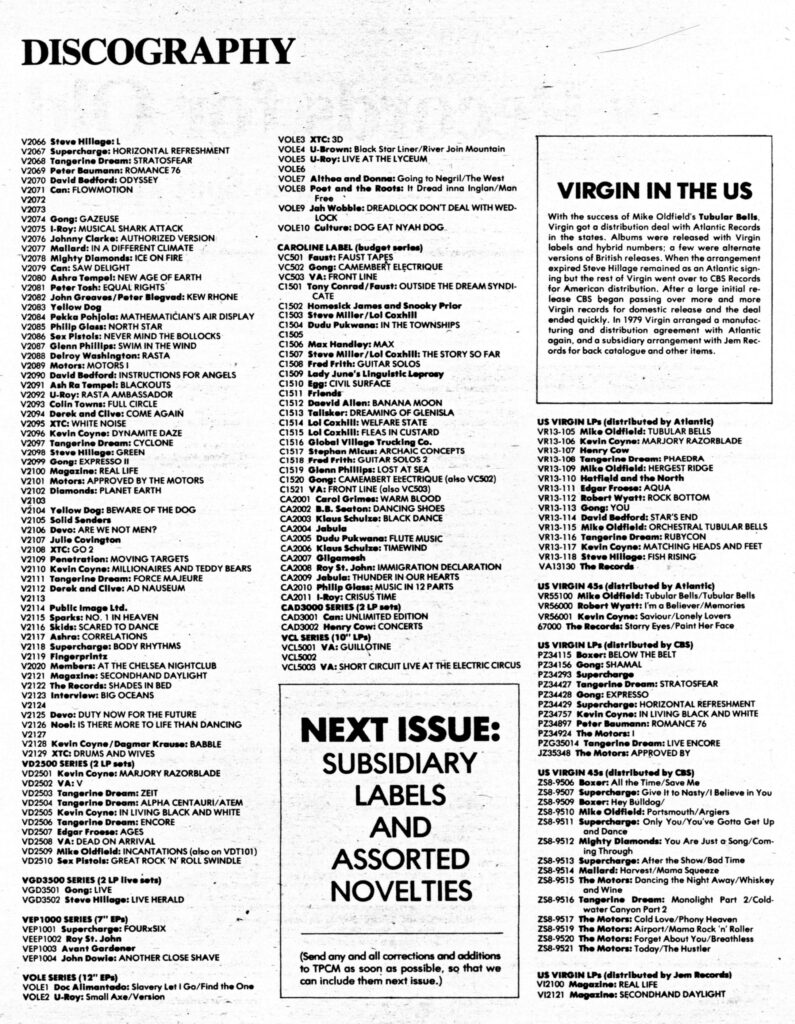

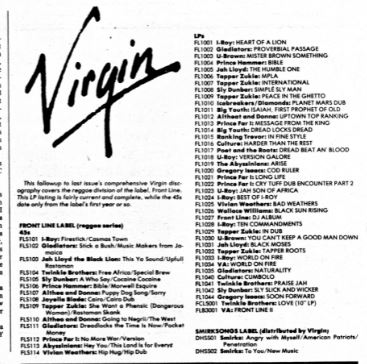

[Yes, that’s how abruptly the article ends. If more was said, or if there were at least a more graceful conclusion, it’s been lost to the ether. The discography below was included with the original piece.]