By Steve Erickson

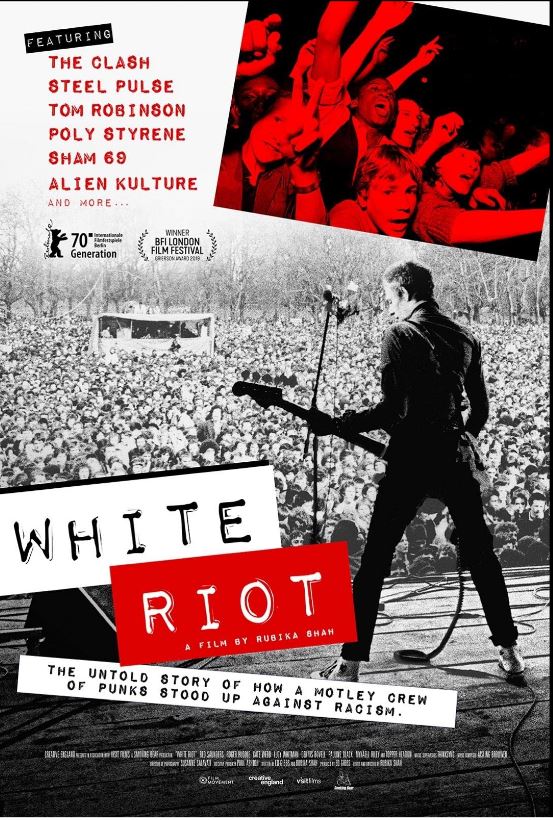

The new documentary film White Riot covers the first two years – 1976 to 1978 — of the British activist organization Rock Against Racism. Director Rubika Shah’s style, which incorporates animation and quick edits, builds on the energy of the punk scene and includes plenty of exciting music.

RAR published a fanzine, Temporary Hoarding, that featured interviews with musicians discussing politics. The group’s founder — photographer and radical theater performer Red Saunders — was inspired to action by Eric Clapton’s racist stage rant in praise of far-right British politician Enoch Powell, in which he claimed a need to “keep Britain white” as well as statements by David Bowie and Rod Stewart in support of fascism or xenophobia. The bitter irony and hypocrisy of Clapton, who built his career on Black American blues and whose first solo hit was a Bob Marley song, voicing such racism was not lost on Saunders, who called him “rock music’s biggest colonialist” in a letter to the NME.

While Saunders was old enough to have been a hippie in the ’60s, Rock Against Racism took off through the punk scene. While Britain’s neo-fascist National Front took the Nazi references used for shock value by the Ramones, Sex Pistols and Siouxsie & the Banshees literally, trying to recruit young fans while attacking Black and Asian people in the streets, Rock Against Racism organized concerts of white punk and Black reggae groups. Steel Pulse, Misty in Roots, the Tom Robinson Band, X-Ray Spex and the Ruts were regulars. RAR was a decentralized organization, encouraging rock fans around the UK to put on concerts in their own towns.

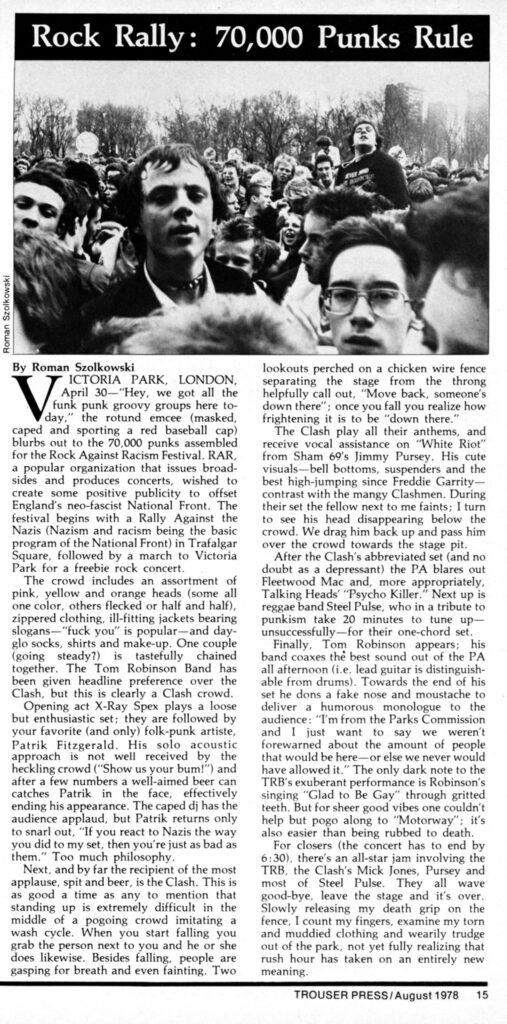

For her film, Shah – who grew up in Saudi Arabia — interviewed the singer of a long-forgotten Pakistani-British punk group, Asian Kulture, who took part and even recorded a single for the RAR record label. The film culminates in a protest march and concert in London’s Victoria Park on April 30, 1978, finishing with riveting footage (originally used in the 1980 film Rude Boy) of “White Riot” by the Clash with Sham 69 singer Jimmy Pursey adding vocals. (Much of the drama in White Riot arises from RAR’s efforts to push Pursey to risk angering his band’s skinhead fans with an explicitly antiracist statement.) The film ends there, but RAR continued, launching branches in the U.S., Australia and even apartheid-era South Africa. Performers as popular as Pete Townshend took part. A current organization, Love Music Hate Racism, has carried on its mission since 2002.

I interviewed Rubika Shah by phone earlier this month.

How did you first learn about Rock Against Racism?

Rubika Shah: I saw the footage of the Clash performing in Victoria Park. That was when I first heard about it. That footage was so great. I found out the whole festival was put on by Rock Against Racism. I thought I would’ve known about something like that, so I asked around “What is this?” Many people didn’t know, so I started digging deeper and learned that it was started by a bunch of everyday people working at a print shop who had this idea two years before to start putting on gigs to support their politics.

How did you put together the cut-up animation?

We made a short film called White Riot: London a few years ago and used that as an opportunity to experiment with different animation techniques. We used 2D animation, and it looks quite punk and scrappy. It’s actually quite difficult to do, because it’s all about getting the frame rates right. There’s a lot of trial and error. I worked with an amazing animator, Levan, who was able to pull it all together and create these glitchy montages. That became the animated language of the film.

Were you trying to copy the look of Temporary Hoarding?

We were inspired by that and the general punk graphics of the time: the cut-up-and-paste aesthetic. If you watch films made at the time, basic animation, they would have just put images onto a reel and cut them together. We took inspiration from that and made it look really rough.

The period footage you use looks really good. Did any of it need to be restored?

We spent about a week restoring it and didn’t get to nearly as much as we would’ve liked. It was a lot of fun. You’re making the picture quality better, but it’s really expensive and time-consuming. We had to pick and choose which bits, narratively and also in times of the tape transfer quality, to use. The girl we worked with was brilliant and spent a few extra evenings doing extra restoration work on the carnival sequences and the march at the end. We wanted to make it “ping!” At the time, we were making the film for cinemas, so we wanted it to look as bright and vibrant as possible.

You began work on this project five years ago. Did it feel like a different political climate then?

Nothing stood out back then. In the UK, there was austerity. Things were getting hard. We were quite a few years past the big recession and credit crunch. But we could pick up on things on the edges, being out and about. Just a feeling that things were changing. Then a whole number of things happened: the referendum for Britain to leave the European Union, Britain actually leaving, Trump getting elected.

One thing that struck me as a major difference between the ’70s and now is that celebrities are often very accessible on social media. Eric Clapton’s racist rant probably would have taken place on Instagram or Twitter now. Instead of Red Saunders writing a letter about it to the NME, he could’ve responded directly to Clapton.

Back then, rock stars had a steel wall around them, with a god complex. I imagine Clapton read the NME and saw Red’s letter. But I don’t know if it affected him, because he went on to support Enoch Powell for quite a long time, publicly. Now, maybe it would lead to a massive Twitter war!

Looking back, what do you make of the flirtation with Nazi imagery among early punk bands and their fans? You bring this up in the film when one of the writers for Temporary Hoarding mentions an interview with Adam Ant that questioned him about his use of such imagery.

The reason for it was rebellion against their parents. But when you see those pictures [of Sid Vicious or Siouxsie Sioux wearing swastikas] in isolation as a young kid somewhere, you may already be getting targeted by the National Front and won’t get the irony. There was a lot of disinformation about punk at the time. Even now, when you speak to older generations who aren’t that into music about punk, they say, “Oh, wasn’t that racist?” They aren’t quite sure, because racists were able to take it and repackage it for their own purposes.

How diverse were the audiences at RAR concerts?

The RAR mantra was “Black and white artists together, in equal billing.” They paid everybody equally. It was very egalitarian, in that sense. They would have a big jam at the end, where all the artists would come onstage and it would turn into a big party. The audiences were mixed, but the idea was targeting white kids at risk of being radicalized into nationalist violence and racist ideology. The main ambition was to show that we’re all the same by getting white kids to listen to reggae and participate in a cultural crossover.

How did you learn about Asian Kulture?

We found them quite late. We knew about them when we were making the film, but we only found their lead singer towards the end of directing it. We thought “This is an incredible story, and we’ve got to weave it in somehow.”

The film only reflects the first two years of RAR. Why did you choose to cover just a short part of its existence?

I originally wanted to cover the first five years from start to finish. It ends after the first two years because I wanted it to end with a bang. The Victoria Park concert was the first moment where it went from being an underground, grassroots movement to a near-mainstream presence. We decided on that for a template for the film, with about 10 different endings. We just kept re-editing it. Some had more of a coda, even going up till today. Others went on to explain more about how RAR went on for five years. When we showed out to people for feedback, ending with the “White Riot” performance clip goes out on a sense of euphoria, with a real boost. The film goes to quite dark places, but then it ends with a great performance. We wanted people to leave the cinema like they had watched that performance live.