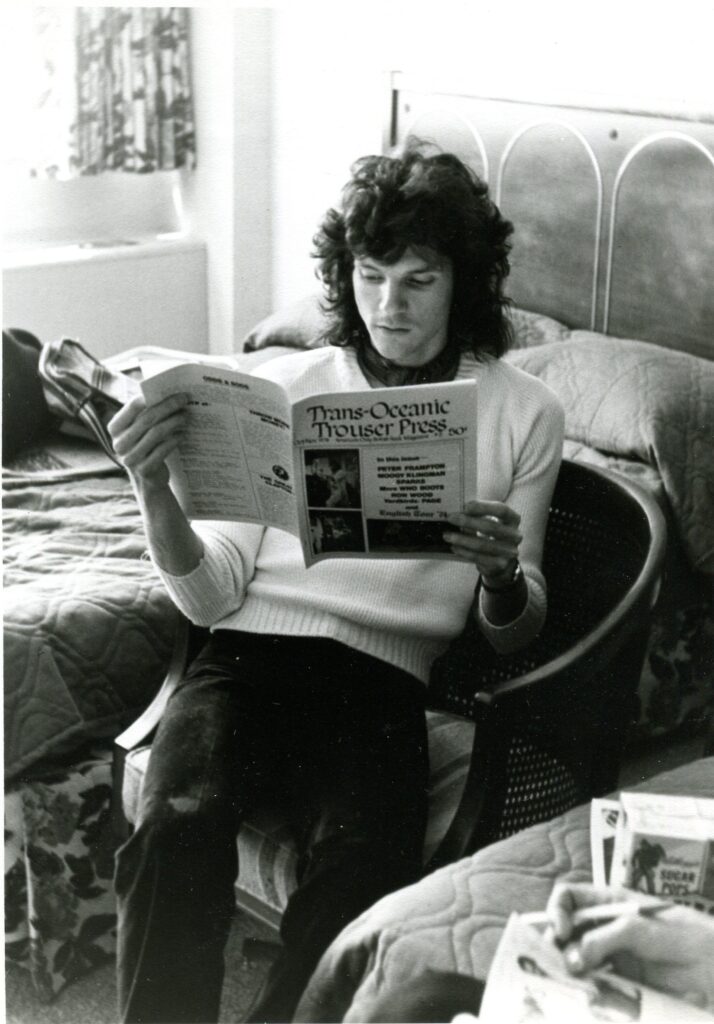

This interview originally appeared in Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press 9, June-August 1975

By Ira Robbins and Dave Schulps

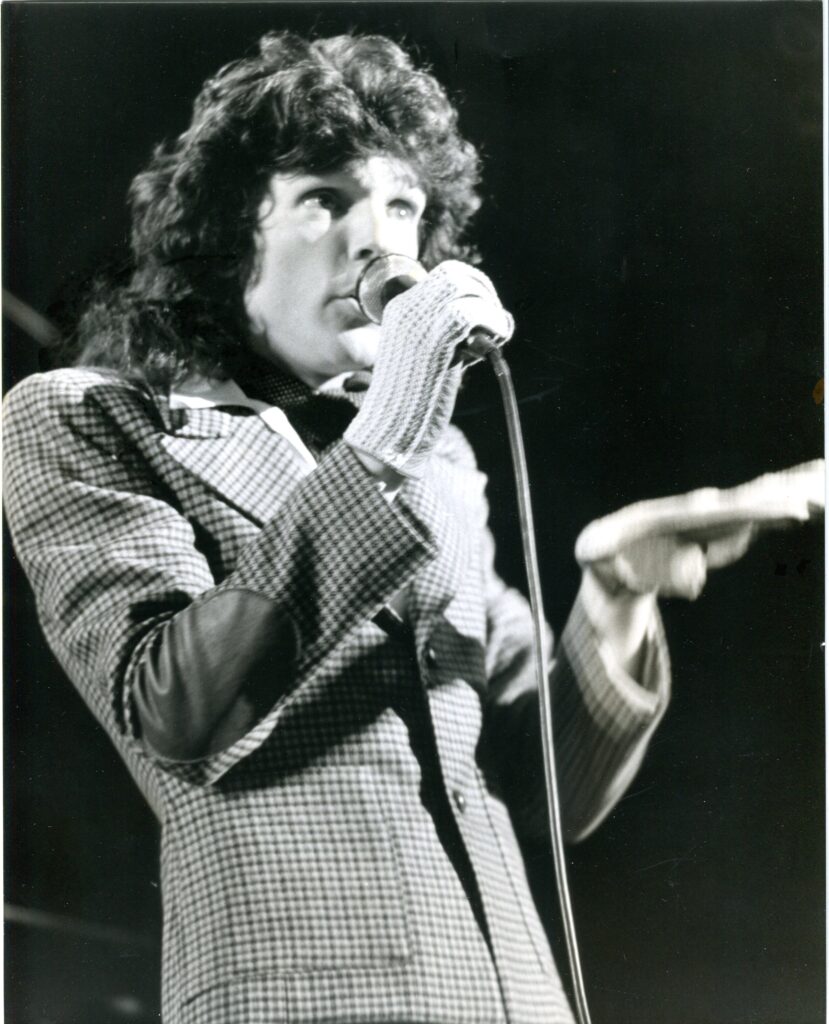

On the occasion of Sparks’ first tour of America, we got a chance to speak to Ron and Russel Mael before their New York date early in May. Like several other top pop bands in Britain, they are articulate, intelligent and totally convinced that they have no equals, musically, in the British charts. Although we wouldn’t go that far, they are definitely a unique and talented group, a fact confirmed by the thoroughly enjoyable show they present.

IR: As Britain’s only American rock band, what is it like to become British pop stars after looking up to British pop stars?

RON: One thing, just to clarify, is that us looking up to the British pop stars was only a part of it, ’cause we liked all the people like the Who, the Move and the Kinks, but then we liked a lot of other people, too. So it wasn’t our ideal to be a Los Angeles British band, and the reason for us going to England was just out of frustration and desperation that the situation was not making it in Los Angeles. It was terribly exciting, and still is, for us to be playing in England and receiving all the buzz that goes on and having hit singles and being on Top of the Pops, it’s just that that isn’t the end.

DS: Who are some of your other influences?

RON: I really like the Beach Boys and all that L.A. sort of flair to it.

RUSSELL: Jan and Dean.

IR: What was it like being Halfnelson?

RON: That was just an artsy-craftsy sort of situation where we weren’t concerned about playing in front of people and we just did things.

RUSSELL: We didn’t know what we were doing at all. We still don’t know what we’re doing.

RON: We were not knowing what we were doing in front of a lot less people. It’s more fun not knowing what you’re doing in front of more people than less. We always thought at that time that, all things being equal, we had elements that were incredibly commercial, so we were just waiting for the time to come along when it would click on that sort of level, but meanwhile we just kept going.

IR: You really thought that Halfnelson could have been a major American band?

RON:· Now one problem with it that we saw a while later was that the execution was not as assured as it might be. In the present format of the band, the playing is more assured so that it can’t be knocked as a band, whereas you might hate Halfnelson, or you might hate guitars being out of tune.

IR: Why was it so much easier to make it in England than in America? In America you were really starting to build a very strong little cult.

RON: One thing, the audiences there are younger and more receptive to new things, I think.

RUSSELL: It’s not as Beatle-oriented there. Here, we found out to our dismay that the Beatles are still a pretty big band here and that’s really amazing and we’ve driven around a lot, and you turn on the radio, and they’re still having Beatle competitions and Beatle giveaways and Rolling Stone weekends. In England it’s not that way at all. There’s a new generation of kids that hasn’t been brought up on Rolling Stones and the Beatles, and Eric Clapton isn’t a hero anymore. Clapton’s still a figure to be reckoned with in the States, but in England the kids don’t really care about Eric Clapton that much. They’re really open to new things, and it really gave us an opportunity to be one of those new things.

RON: I think there are a lot of limited-appeal bands in Britain which still flourish a bit. People have asked how we’re gonna change what we’re doing for the States, thinking that maybe we were one of those limited-appeal bands. We haven’t altered anything for America. It’s the same band you’d hear in England, only playing in the States. The reaction has been almost unwarranted at times and really exciting for us.

RUSSELL: We played in Los Angeles, the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. It was the best concert we’ve ever done, including any English concert, any European concert and it was in the United States, in our hometown. The reaction was exactly as it’s been in Europe when there’s people yanking at your leg. We were really shocked. In America, before our TV appearances, I don’t think the band was something to be reckoned with. It really put Sparks on the map.

DS·: You said you really like touring, but when you were in America you really didn’t tour extensively.

RUSSELL: No one wanted to have us.

DS: You originally started as a studio band.

RUSSELL: Yeah, originally it was just three people: Earle Mankey and the two of us. Earl had a tape recorder and we had some songs. We didn’t really care about playing live but after we made tapes and found out we couldn’t get signed with those, we decided that the only thing to do was to play someplace. We couldn’t just play with the three of us so we added Jim Mankey and Harley Feinstein.

DS: What’s happened to the Mankey brothers?

RUSSELL: Earle we just saw a couple of days ago in LA, he’s the head engineer at the Beach Boys’ studio. Jim’s gone back to university and Harley’s gone back to university, he’s gonna be a teacher.

IR: Do you listen to any bands that have records which might exchange places in the charts with yours?

RON: We listen to the radio, it just isn’t that interesting. A lot of people trying to cause a stir as personalities where they don’t have any music to back it up. It can work a lot of times in England because they kind of go for that sort of thing. But then there comes a time when you have to release a record, sad to say, and that either holds water or it doesn’t.

DS: Are you planning to record anything while you’re here?

RUSSELL: No, we’re being produced by Tony Visconti, and he’s got a studio in his house. We’ve finished two songs already, and when we go back to England, we’re going to finish the LP.

RON: He’s really a good person.

RUSSELL: One of the two new songs we recorded lasts four-and-a-half minutes. The idea was to release that as the next Sparks album, just that one song, because it’s got so much thrown in. We put everything into it. We’re thinking of retiring after that.

IR: Did Alice Cooper steal “No More Mr. Nice Guy” from you?

RUSSELL: Yeah. It’s a totally different song but they had seen us play a lot at the Whisky in L.A. as Sparks and Halfnelson and we always did that song and it was always the one song that went down the best, sort of the only song that got any reaction at all, and that’s ’cause it has a really moving chorus and we didn’t flub that one up too badly. That was one thing people really remembered the band for. They really liked the band and they just took it. They took the whole idea of the chorus, they changed the melody and all.

IR: Who are the women on the cover of the Kimono album?

RUSSELL: They’re from Stomu Yamashta’s Red Buddah Theatre. A lot of people wondered if it was us, but it definitely was not.

DS: There’s a rumor that you sang back-up vocals on “Waterloo Sunset.”

RUSSELL: No, that wasn’t true. Anything else?

RON: Trevor White is not joining the Rolling Stones.

DS: What got Adrian Fisher fired? Was he into too heavy a thing?

RUSSELL: Asshole. The other was that he wasn’t too concerned with being in Sparks. He’s a really good guitarist, but he’s from “de blues skool.” You can’t fool people into trying to be excited about what you’re doing.

IR: Would you like to clear up the ultimate all-time Sparks rumor?

RUSSELL: You’ve got a better one than the Kinks’ thing?

IR: That your mother is Doris Day and your brother is Terry Melcher.

RUSSELL: Yes, I’m Terry Melcher.

RON: No, we actually mentioned that just as a giggle when we first went over to England, not thinking that anyone would take it seriously. We were in Copenhagen and I got a call at the hotel from a lady saying “Is Mr. Melcher there?” I said “No.” She said, “We have on our records that you’re Doris Day’s son…”

RUSSELL: “…and we’ve been trying to get in touch with her because we’ve got publishing royalties for her songs in Denmark and we’ve got all this money sitting in the bank and we’re trying to give it to her but we can’t get in touch with her so do you want to pick up the money?”

RON: If you want to be Terry Melcher you can go pick up a very large sum.

DS: How long does it take to write a typical Sparks song?

RON: Well, it takes a long time because you have to go through a lot of stuff you don’t use. You sit down for ages and ages and then something will pop up, maybe rather quickly.

DS: They don’t seem like the kind of things you just knock out.

RON: Yeah, I don’t. I wish I could, I really wish there was a fast way because it’s really boring. ·But when one comes up, then it’s all worth it. When it’s not coming up then it’s not worth it at all. Each song is its own reward.

And these are transcripts of phone interviews conducted in 1990 by Ira Robbins for the liner notes of Profile: The Ultimate Sparks Collection (Rhino, 1991). The two interviews are intermingled in the song comments.

RUSSELL MAEL

Both of us graduated from UCLA. He was one quarter away from a masters in art and graphic design. My degree was in theater arts and English. I went to Palisades High. Ron went to Uni High.

We met Earle [Mankey] at UCLA. He put up a sign on the bulletin bord: “Engineering wiz wants to connect with other musicians.” None of us were from a live music background, it was all recording. We kept making recordings with him and never played live. That helped shape what we do. We never did things from the standpoint of whether things would work in front of an audience. That’s why we were able to be as quirky as we wanted to be because we didn’t worry what people would think. Harley’s now an attorney in LA. Everybody in the original band is doing OK.

American Bandstand

Probably ’72. We did “Wonder Girl” and “No More Mister Nice Guy” (with the hammer). We were in such a dire financial situation when we managed to get on that show. We were on the food stamps program at the time. We went into a grocery store and were using our food stamps to buy peanut butter and stuff and this checkout lady recognized us from the show and said, “My son loves you guys.” Meanwhile, she’s going, “We need food stamp approval at checkout 23.” The whole store was looking at these big rock and roll stars — it was a humbling experience.

Anglophilia?

Definitely. We wanted to look like the original Small Faces — hairstyles and fashion. It was so foreign to what was going on in LA at the time. There was such an aura for us about what was going on in England. Ron and I had gone to England during the summer two times prior to having a band, and slept in 50 cents-a-night youth hostels where they gave you chores in the morning. We would go to music festivals — the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Pink Floyd, Cream. The English scene was so exciting for us. The opportunity to go live there and get an English record deal was like a dream.

People still think we’re English. We have a really nice video of the last show we did in England — we haven’t played there since that period — in Croydon. [Tony] Visconti did the live sound. The final shot of the whole show is this girl leaping on my back and flattening me. Pretty wild stuff.

It was pretty uncompromising in what it was and we were lucky that we had people around us that were supportive of that. Nowadays everything has become so geared toward what niche it fits into, radio-wise. Those days are gone — that way of looking at what a band can do. On the whole, people can’t do uncompromising music and then have it become commercially successful, too.

We were doing lyrics that were substantial and offbeat but still had this teen following.

Whomp That Sucker cover

That was a publicity boxing match in London. No ribs broken. They set up a full-size boxing ring in the London Hilton Hotel. We had a couple of weeks of training with an English boxer. It was three or five rounds; it was staged and Ron was to be the winner, so he knocks me out, and they carried me out of the ring. That was the end of the promotional event. It was done very seriously. There was a strange vibe to the whole thing.

We were violently attacked for this blasphemous thing of combining synthesizers in a band and doing dance music — disco at the time. But we had three really big hits from that album, so the public in England and Europe really liked what we were doing. “Beat the Clock” was a much bigger hit than “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us.” From the public’s standpoint, it was really successful. Critically, though, we were lashed out against. Now, 10 years later, a good portion of the English bands in the Depeche Mode ilk — we know a lot of them and they say that their careers were founded on that one album [#1 in Heaven].

What would have been your alternative career?

I don’t even want to think about it. English teacher…and be incredibly frustrated the rest of your life.

RON MAEL

We had had two albums in the States that had sold maybe 4,000 each. That early band had toured in England, and when we came back things were at a point where even the Whisky wouldn’t let us play anymore. That was our lifeblood, so Russell and I got an offer from Island Records to sign with them in England, but they only wanted the two of us. It was incredibly difficult for us to decide what to do. We were friends with everybody in the band and we liked the situation in the band, but it was at a standstill and we had to do it if we wanted to be in music. So Russell and I moved to England in the summer of ’73 without thinking too much about what this was — one of those big life decisions.

Our parents had moved to England, and we lived in an apartment. Our parents had a piano, and every Sunday I would take a bus over there and write songs on their piano. I don’t recall any of the Kimono songs being from the States. “Simple Ballet” [from the first album] has a bit of that feel to it, but it was carried further.

We’d finally gotten all this together in England when there was an incredibly big energy problem. First of all, they were rationing power so we had problems recording the album. Then Island told us the record might not come out because they didn’t have the vinyl to press it.

“Wonder Girl”

Russell: That was one of the original Earle, Ron and Russell songs. The final recording that Todd Rundgren produced stayed really true to our home demo of it. Todd really picked up on what we were doing at the time. He took our original tape and, pretty much intact, that’s what came out as the Halfnelson album. He enhanced the sound quality, but as far as what was on it…

“Wonder Girl” was the first song we released, and it was a small hit – #80 or something. We thought it was easy. It was number-one in some big Alabama city.

Ron: The surprising thing to us was that it actually got into the charts. Everybody was telling us — and to this day still tell us — that we’re a bit eccentric and out of the mainstream and, lo and behold, the first song that we released got into the Billboard charts. The whole thing was kind of a giggle to us. We were ecstatic just doing this. We would go in the studio and have a blast and nobody would keep a check on us. Todd was even pushing us to be as eccentric as we were and maybe even more so.

“(No More) Mr. Nice Guys”

Russell: It was one of the original ones as well. It had a heavier, aggressive guitar feel to it. We used to perform it at the Whisky; when we started performing live that went over real well. Alice Cooper came to the Whisky and saw us. We’re resentful to this day that he stole, without crediting, our wonderful title. He changed it slightly. The songs are not the same, but…there are certain similarities.

Ron: In our Whisky a Go Go playing days, Alice would come to see us. We tried to do as many different things as we could at the time and this was our, excuse the expression, rock song. A lot of our songs didn’t go over so well live but we liked doing them anyway and this one actually went over pretty well live. Our live shows at that time — we would do things like “Wonder Girl,” but also stuff like “(No More) Mr Nice Guys,” “Do Re Mi” and “Whippings and Apologies.” We were hyperactive. We would take songs that were fast on our album and with the excitement of playing live they would turn out to be twice as fast. Probably at the end of the song they would be three times as fast.

“Girl From Germany”

Russell: People in Germany were real happy about it. We really liked Europe and the whole continental mystique.

Ron: That was in the days when Russell was writing more. He wrote the music. The lyrics for our songs are not a Joni Mitchell thing where she can refer to a specific inspiration. The songs aren’t usually based on any outside event. A lot of times we come up with a title and then it builds into something. There’s a little universe we’ve developed over the years, with mythical people and situations. It’s just an imaginary thing. We’ve tried to write things that slip out of that area, but our strongest things are those sort of situations. “Girl From Germany” was just a title, and one thing led to another. I really like the lyrics. I remember just laying on a bed and writing that one.

“This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us”

Russell: That was the first song released from Kimono. It got to number-two. We were offered Top of the Pops, but we didn’t have the proper British Musician Union papers, so we were cancelled. After a few weeks, we were finally admitted into the Union then we got to do TOTP. But the song by the Rubettes, who had replaced us on TOTP, went to number-one. We’ve been proud members of the MU ever since.

Ron: The gunshot came from a BBC record. That was controversial. We debated for hours whether it was too much of a gimmick or not. There was an extra verse to that song that was edited out.

Before we went to England I wanted to be able to play keyboards better, and I was playing a lot of Bach etudes to try and become better. A lot of the stuff on Kimono was influenced by that, because a lot of it is based on keyboard playing and phony classical moves. Everybody assumes that song just got to be a huge hit, but everything that we’ve had that’s been popular in any way came very close to not being popular. The record was out, and everybody at Island liked it, but there was a competition on Capital Radio between “This Town” and Harry Chapin’s “Cats in the Cradle.” It was a phone-in show and we phoned in for our own record a lot, and that was how it got to be played on Capital Radio. One thing led to another. That whole period was pretty explosive.

“Hasta Manana Monsieur”

Russell: Not a 45, Just an excellent album track. Another one of those European-based songs. A screwball pop song.

Ron: It has to do with wordplay, and the sounds of things. The fun of making sentences that aren’t tied down to one language. We were wiseasses, and it was a way for us to show how international we are. We felt, in certain ways, that we were more sophisticated than a lot of other rock bands. One way we could prove it was by doing chansons instead of songs.

“Talent Is an Asset”

Russell: That was a single in America, not in Europe. That was always well received live. People requested it.

“Amateur Hour”

Russell: One thing that’s really exciting about England is that the lifespan of a single is about six weeks. “This Town” was still doing really well when we came out with “Amateur Hour,” which was a really different kind of song. It was neat to see two songs that were really different in nature become back to back hits.

“Something for the Girl With Everything”

Russell: That was another English hit single. Another one that was melodically in the style of “This Town” — one of those melodies that couldn’t have been anyone but Sparks. Ron wrote it on a keyboard and then forced me to sing those acrobatic melodies. It was a really unique style of writing.

“Never Turn Your Back on Mother Earth”

Russell: Another single, and the first time we tried a change of pace. The record company was real nervous because we were known for the hyper style of things, and this was the first ballad-like song from us. They were worried at the time what the public might think of it, but it did really well. There are two other versions. Tony Visconti’s wife at that time, Mary Hopkin, did a version as a demo that sounded great but was never released. More recently, Martin Gore from Depeche Mode did a version.

Ron: We were trying to something that wasn’t so hyper, a change of pace which wasn’t sappy. We were wrapped up in our own little world, and we didn’t think those things sounded as much alike as other people did. People would say the songs on Kimono all sound the same, but it didn’t seem that way to us. To us it all sounded different. We were concerned about that and we were trying within the limits of what we do to find different ways of doing things. The other side of it is that we were playing live a lot then and we also were concerned that these songs would work live.

In England at that time, anything we would do live would work. It was crazy. The downside of it was that the reaction was so hysterical — we were drawing a lot of young girls – that our musical credibility suffered.

“Achoo”

Russell: The end of it is a series of echoing “achoos”. That’s all me. It was done without the aid of any outside nasal stimulation. Performing it live was hard.

“Propaganda”/”At Home at Work at Play”

Russell: They were two separate things. We wanted to try an a cappella ditty, so we did “Propaganda,” kind of operatic in feel that you’ll notice in several Queen albums that followed. That didn’t fit into any mold — a 30-second-long a cappella song.

Ron: At that time, we were trying to figure out different ways of combining things, and doing the “Propaganda” song a cappella was a challenge for us. We’re not trained musicians or anything. Russell would sing something, and then sing another thing that sounded good with it.

“Get in the Swing”

Russell: We wanted to work with Tony Visconti. We liked what he had done with Bowie and T. Rex. He liked what we were doing, and we wanted to make use of his talents as an arranger. We actually performed this live on TOTP for reasons I can’t remember. The musicians had to go on the show with us. They had trouble: the song is in different sections, and it continually shifts tempos. The TOTP orchestra isn’t used to so many tempo changes in one song. I remember Tony conducting and they were having trouble keeping up with him.

Ron: This got into the Top 30, but not into the Top 10 in England. We were so upset at people not accepting it in a huge way, that we were going to do a version of “Louie Louie” and release that. You get so mad at the reaction to what you’re doing that you say it just doesn’t matter anymore. We shouldn’t have thought about it, we should have done it.

“Looks Looks Looks”

Russell: It was written for a big swing band and Tony took on the challenge of scoring it. We did the song on TOTP and the rule is you have to re-record all the songs, so we had to get this big band in to play the thing again. It was strange watching all these stuffy English musicians trying to play on a Sparks pop record.

Ron: We did this live on TOTP, with these 75-year-old BBC big band musicians. Tony Visconti was leading them, and it was rhythmically wandering. We changed producers on that album, and we wanted to make use of Tony’s abilities as an arranger. On one side we didn’t look at what was happening sales-wise with our records, but the sales in England of Propaganda weren’t quite as good as Kimono, and we wanted to do something different. At that time, if you faced that situation, you would push off in a different direction. Now the immediate reaction to that situation is to come up with something that’s more middle of the road. We were naive enough at that time to do what a lot of people thought was a really self-indulgent album. But to us everything is self-indulgent — that was our whole reason for doing music.

“Lost and Found”

Russell: Non-LP. I like this, it’s real raw and guitar-y. It didn’t have a lot of keyboards. It was raw and aggressive. In those days, we would always record a few extra things for B-sides. We did “The Wedding of Russell Mael and Jacqueline Kennedy.” It was fun to be able to come up with things whose main purpose in life was being B-sides.

Ron: We would write a lot of songs. Muff Winwood said we had to come up with 30 or 35 songs in order to have an album’s worth of material. This was one that didn’t make the album. We would rehearse all the songs in the studio first and, generally, we would know what was going to be on the album during the rehearsal period. Others, like “Lost and Found,” that weren’t quite as strong would be slated for B-sides. I thought B-sides were a really nice thing.

“Big Boy”

Russell: We had left our English band and were contemplating moving back to America. We didn’t have any musicians to play with and Joseph Fleury is from New York and he had some contacts and people were presented to us as friends of friends. These people were there, and they could all play very well. And to do what we were attempting to do at the time, it seemed like it could work out.

Ron: We always liked the early Who, and this is our interpretation of a Who song. To our chagrin, it was a part of the Rollercoaster movie, and a lot of people who know nothing about us know us as the band from the Rollercoaster movie. We’re in the film, lip-synching. They tried to get KISS, but they turned it down, and they got Sparks instead.

“Nothing to Do”

Russell: This was a big favorite of Joey Ramone’s, and he was always trying to convince the rest of the Ramones to do that song. I would have loved to hear their version of it.

“I Like Girls”

Russell: We had proposed doing a version of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” with Marianne Faithfull. It was going to be a solo single. We had contacted Rupert Holmes to do a lush orchestrated version of that song. Marianne Faithfull decided she didn’t want to do it after all — doing a Beatles song brought back too many personal memories of that period that she didn’t want to relive — and backed out of the project. But Rupert had already scored it, so we did it with him. He did an orchestrated version of “I Like Girls,” an old song from the Bearsville days, and we had a good relationship with him, so we asked him to do our entire album. But as it turned out, we decided that the direction for the next album should be a stripped-down version of Sparks — less emphasis on keyboards and more guitars. Rupert’s strength is in his orchestration, and we told him to abandon everything he’s good at and do a stripped-down, sparse guitar record. We were kind of unfair to Rupert in taking a guy who’s good at one thing and telling him don’t do any of this stuff, do it that way.

Ron: We had played that back in the Whisky days, and I don’t know why we didn’t record it. I think we had recorded a version of it with Todd at one point, but I don’t know what happened to it.

“A Big Surprise”

Russell: We were bandless again. We were back in LA. We decided to do an album with session musicians. I like the songs, but I don’t like the fact that it was played by session musicians. It has a sterile quality that was not in keeping with the nature of the songs. They came out blander-sounding than they should have been.

Ron: It’s kind of bland. There are things on that album [Introducing Sparks] that are a lot more interesting in that song. We had gone to England to do some promotion – it was the height of the punk era — and going over there with a song like “Big Surprise” as usual we were working in a different musical mode than other people.

“Over the Summer”

Russell: We had done a demo of this that has more character than the final one that made it to the album, before we stuck on all those high-priced musicians. Our demos were just a keyboard and voice, or acoustic guitar. Drum machines came later.

“Number One Song in Heaven”

Russell: I really like it. We were going into no-man’s-land, combining synthesizers and a dance… Kraftwerk had done some stuff, but we applied a band mentality. We had loved “I Feel Love” that Giorgio Moroder had done with Donna Summer and were looking for a way to combine that sort of thing with our kind of outlook and melodies. I don’t think we analyzed what we were doing that much: we just heard that one song and were really amazed, it was a breakthrough kind of pop record. We didn’t know anything about synthesizer technique, so we needed to work with someone that knew the technology and apply it to what we were doing. Having no band at that time, studio-oriented work was perfect for us. We contacted Giorgio and he took on the challenge to work with a band. He’d never worked with a band before.

He’s a great guy, but the work situation… He’s used to working with one singer and molding the whole production. For us, that was difficult sometimes. But we were happy with the results. He’s more used to working with traditionally good singers. It was difficult for him to work with someone like me that isn’t schooled in the same way.

“Beat the Clock”

Ron: We’re always trying to put ourselves in different musical situations. We really loved “I Feel Love” and through a German journalist we were introduced to Giorgio Moroder. He had been wanting to put together what he thought was a rock band. So we worked together. We recorded over a bunch of old Donna Summer master tapes, because he didn’t want to spend a whole lot of money on this project. Both Giorgio and ourselves went into this not knowing what the result was going to be. Giorgio isn’t really a hands-on player, he’s more conceptual, but he was actually there playing on that album. It was before drum machines, so you’d put down a click track and the drummer would come in for ten minutes and pound his foot on the floor. Giorgio wrote the music for “Number One Song in Heaven” and “Tryouts for the Human Race,” and I wrote both the music and words for “Beat the Clock.”

After we recorded this album no one was interested in signing it. Then someone at Virgin in England heard the album in an office in Germany and liked it and got ahold of Giorgio. We went to England to do a lot of press and we were absolutely crucified. We consider ourselves a rock band, and for a rock band at that time to be doing disco was disgusting to critics and other people. To be put on the defensive was really difficult, but then the record got enormously popular in England. People think the Sex Pistols was this huge selling thing, but “Beat the Clock” sold more than they [did] at the time. We felt we’d committed some major sin and meanwhile this thing was popular.

The last thing we wanted to be was disco. We knew it wasn’t hip, but we knew that the combination of electronics and a dance beat was exciting to us. We thought working with Giorgio would have some effect, but it turned out to be a negative thing — people were actually less disposed to like it. That record, in all modesty, was the inspiration for a whole movement of bands, the whole Depeche Mode sort of thing. They acknowledge it when we meet them, but in the interviews it’s always David Bowie and Bryan Ferry. Erasure and Duran Duran have said things about us in print.

“When I’m With You”

Ron: We were in England doing press, and I found a piano rehearsal hall, so I would go there every morning and try to come up with things. I wrote that song there. We were still working with Giorgio at that time. He’s a very strong producer, and wants to be involved in the selection of material. I probably played him 25 songs and he rejected all of them except “When I’m With You,” and he still thought it needed a new middle. So I wrote a new middle for that. I think it’s a good song, but it’s kind of sappy.

Julie Burchill, the most bitter person on the face of the Earth, liked some of the lyrics. The album [Terminal Jive] never came out in the States and it didn’t do anything in England, but in France this single was the biggest thing we ever had. We spent eight months in Paris, doing television shows working on that song. It was bizarre. We liked doing those kind of television shows, but it was with a song we weren’t the proudest of. It was selling these enormous quantities. Usually the things of our that do well we’re really proud of. It’s a really good song but it doesn’t really appeal to me, except that it brings back fond memories of living in France.

“Tips for Teens”

Russell: We were back to using a lot of harmony again. Having a band being quirky sounding and songs that were powerful and melodic. “Tips for Teens” always reminded me of an album like A Quick One by the Who. Lyrically, there’s a certain similarity of slant. Soundwise, it’s aggressive instrumentation with melodic melodies on top of it.

We’d met an LA band called Bates Motel and got along really well with them personally. They were at a point in their career where they were at a stalemate as well. We asked them if they wanted to join us en masse (except for a second guitar player), and took the whole Bates Motel band. Then the songs were written for that album [Whomp That Sucker] We spent a lot of time rehearsing with the band before we went into the studio. We’re pretty firm on how we want things to sound, but everybody were into the spirit, so they did lend something to those recordings.

“Modesty Plays”

Russell: We were enlisted by a screenwriter friend of ours in Los Angeles to do a theme song for a TV version of the comic strip Modesty Blaise. The show never materialized, but we really liked the song. We’d given it to our French record company and they released it as a single. It got massive airplay on KROQ in Los Angeles as an import and became a well-known song in LA. We’d do it in concerts here. A different recording of the song came out on the Curb album [Music That You Can Dance To]. For legal reasons, we called it Modesty Plays.

“Angst in My Pants”

Russell: The same band again. We recorded in Munich again, with Mack. Ron came up with that title. We had another song called “Angst in My Pants” with a totally different melody. It was going to be on the album, but we didn’t like it that much. We needed one more song for the album. We’re usually well prepared before we record, but somehow we were one song short. We’d finished recording all the other songs. One day in the hotel in Munich, Ron came up with that melody and stuck the old title onto the new song. Mack really liked the song and we recorded it.

Ron: We’re definitely not repelled by sex, but we’re definitely repelled by the typical crotch-rock stances, so we went out of our way to avoid anything that even approached a come-over-here-baby-let’s-hop-into-bed sort of thing, but I suppose in “Angst in My Pants” we found a way to channel those urges in a Sparks kind of way.

We had recorded the entire album but we needed another song, and it had to be done the next day. We had recorded another song called “Angst in My Pants,” so during the night I came up with this one. The song opened things up for me musically a little because it’s more sing-y and less herky-jerky. A lot of times as a writer you’re looking for a breakthrough in the way you write that can lead to other things. At least for me, it’s difficult writing songs and sometimes I get to a point where a way of working is cut off. Maybe it can’t be seen in anything we did later on, but it was really important to me because it led to other things as far as writing.

“I Predict”

Russell: An ode to the National Enquirer, an ode to the checkout stand. It takes every tabloid headline and makes a song out of them. Live, we just kind of end it, which is wrong but what are you gonna do?

“Moustache”

Ron: In France, we were kicked off a TV show because the guy said I looked like Hitler and he didn’t want Hitler on his show. A lot of people are weird, but French people are weirder. If I had been smart, I would have cut my moustache a lot sooner. I didn’t realize the depth of people’s feelings. To me, it was really a cartoon thing and, if anything, it was Chaplin. But less specifically, it was like a logo on my face. If I had been more commercially smart, I would have altered it a lot sooner than I did.

“Cool Places”

Russell: The Sparks fan club gotten a really nice letter from the head of the Go-Go’s fan club, saying how much Jane [Wiedlin], in particular, was a big Sparks fan. She had even run her own Sparks fan club in the Valley way back when. I thought it was really neat getting the letter, and I liked the Go-Go’s a lot, so I contacted Jane and asked if she wanted to do anything together. Jane said she’d really like to try something together, so Ron came up with “Cool Places.” We went in and did it at Giorgio Moroder’s house without a whole lot of fanfare. It turned out really well. She ended up coming on tour with us — major city shows, all the fun ones. She missed out on North Dakota.

Ron: This was going to be a straight Sparks song. We played her a few songs, and she chose “Cool Places” as the one she wanted to be a part of. We recorded it really fast — a day and a half, and mixed it in one night — at Giorgio’s house. It introduced us to a lot of people that weren’t aware of us before. We got contacted by Rick Springfield to tour with him.

“With All My Might”

Russell: Another one of our slower tunes. We thought this could have been really successful commercially. It sounds like the type of thing that could get played on the radio, but for whatever reasons it didn’t get played a lot. Even the stations that would support us thought it was too soft-sounding. For once in our career, Ron tried to make a song acceptable for an American mass audience — not being overly clever, trying to make them real palatable. The lyrics aren’t humorous or quirky, but they’re still well written. It had a real nice video, a fantasy western motif with us rocking on two real fake horses. The video went counter to the song’s seriousness.

Ron: We wanted to do a song that had all the irony removed and was just a song song. That was what we came up with. I really like it, but people look for the motive behind it and then we can’t get accepted. People are waiting for the punchline, and there isn’t any.

“Change”

Russell: Change is one of my favorite Sparks songs of all time. That’s the kind of song you would hope would be a worldwide number-one. It’s a real special song. It was a real disappointment when it didn’t click commercially. We’d performed it on English TV; the French record company tried to make it work, but it didn’t click. It’s a bunch of different pieces stuck together. It has different sections, and comes back to sections that it leaves for a little while. The lyrics are real poignant, done in a way that’s a little off-kilter.

Ron: We wanted to try something that was really involved. We went to Brussels — we’re friends with the guys from Telex and we went to their studio — and spent a month each on two songs: “Change” and “The Scene.” We wanted to do something that people would either say this is the greatest thing ever or else totally reject. We wanted to do something that was really challenging. “Change” is one of my favorite songs of anything that we’ve done. Partially because it was so much fun to work on. It came out in England and couldn’t get beyond a certain point. If it had been accepted, it would have been huge. We set out to do something that was epic, and we thought we had succeeded. We can’t control the reaction.

“Music That You Can Dance To”

Russell: We had finished the album in Brussells. It was eventually sold to Curb Records. Curb was, at that time, producing a film called Rad. They thought the song would be great for the movie so they stuck it in. That was one of the worst movies of all time.

I really like the album because it’s real pure and focused. It’s rich in the production, and stylized in a certain way that I like.

“So Important”

Russell: This is as close as Sparks will ever get to doing something that is compatible with American radio. I like the melody in a traditional way. I like that song. It was the first album we did in my home studio. It’s not set up for a band playing at one time. We continued working with John Thomas, a keyboard player who’d played and worked with us.

We hadn’t done anything for a while. We weren’t active. David Kendrick was waiting for us, and then he had this chance with Devo. We never broke up, we just ceased to be. Nothing specific. We see them all the time. Les Bohem is doing screenwriting. It depends on how well the Devo album does whether David Kendrick will be our drummer or not.

Ron: We were trying to write good songs in the way that maybe other people might write good songs. We did it all at Russell’s studio. “So Important” relates to songs like “With All My Might,” where people are looking for the motive behind it.