I owe a LOT to the Good Guys: Joe O’Brien, Jack Spector, Harry Harrison, Dandy Dan Daniel, B. Mitchell Reed, Dean Anthony and Gary Stevens.

Beginning around 10 years of age, just as the British Invasion began, my introduction – nay, initiation — to music came through the tiny speaker or the knotted white-wired earplug of a trusty Viscount transistor radio, my battery-powered connection to WMCA-AM, one of the handful of New York radio stations that played rock and roll in the mid-’60s.

“Radio 57 – first on your dial.” That made it easy to tune in, even though the signal was audibly weaker than nemesis WABC, perched 20 clicks higher at 77. (Actually, the bandwidth for AM frequencies is in the hundreds of kiloHertz, so the station was actually tuned in at 570 kHz. Whatever – it’s not like I had a problem with the non-mathematical way batting average percentages were expressed. And 57 was what it said on my radio’s tiny tuning window.)

Other than the folk songs I learned at Camp Thoreau, my early taste in music was entirely formed by what I heard on WMCA. (As a kid, I bought and owned very few records. My big sister gave me some singles, but my small allowance led me to rely on LPs borrowed from the library; when I became a writer and got on mailing lists, my tiny teenaged collection began its inexorable growth.)

I was a slave to the sound, obsessed with every song, contest, countdown, joke and news report the station pumped out. I picked up and devoured Go magazine, the national giveaway music paper (edited by the late Robin Leach!) sponsored by local radio stations, weekly from the counter of some store on Kings Highway on my way home from seventh and eighth grade. And the station’s weekly chart for home study. Naturally, it contained precisely 57 hits of the week, some designated as the week’s “Sure Shot” and others noted, no doubt with pride, as “Former Sure Shots” that had borne out program director Ruth Ann Meyer’s early taste-spotting confidence. (Now that I think about it, what data was used to rank singles? I guess when you’re a kid receiving the gospel, you don’t question who came up with it.)

To distinguish itself from the more showbizzy WABC and the less showbizzy WINS (which went all-news in mid-1965), MCA called its deejays the Good Guys, had them sing funny songs in unison and emblazoned the slogan (in singular form) under a smiley face squiggle on the bright orange sweatshirts you could win by sending in a postcard and then waiting to hear your name announced on the air. I tried and tried and tried but finally was able to snag one for $3.00 during a rare retail sell-off by the station; although it fit me when I was a stocky 12-year-old, it’s now roughly the size of a chunky baby. How does that happen?

I recorded broadcasts by placing a rectangular microphone directly face-to-face on the radio speaker and running it into the reel-to-reel tape recorded I got for my 12th birthday. (I could either have that or a shotgun, my father said at the time. I definitely made the right choice.)

Half a lifetime later, I was myself gainfully employed by a radio company (in a completely off-mic capacity) and had a colleague who’d been an oldies (now called “classic hits”) jock in several markets. One day, I accompanied him to an event at which he introduced to me to Dan Daniel, who had the afternoon shift on MCA and played the countdown my friend Gregory Trent and I listened to religiously after school. I’ve met a lot of famous people, but I admit I was overwhelmed. I told the toweringly tall Texan how much I owed him for my musical education and thanked him for setting me on the path of my life. He couldn’t have been nicer. (Daniel died in 2016.)

The reason I bring all of this up is because of an MP3 my (now-former; I left, he didn’t) colleague Mike McCann sent me, a three-hour 1968 WMCA aircheck. Beyond the simple nostalgia of hearing my 14-year-old world captured in amber, it’s an amazing document of rock radio’s youth, before the audience was fragmented into a dozen narrowly focused isolation tanks. It’s a window into a time when pop music was a thousand things all at once, when youth culture welcomed the myriad results of its awakening with open arms and embraced whatever flowed forth. I listened to the file once and was transported; but I was also provoked into thinking about what it all meant, then and now. So I played it again, this time with a Word file open.

It’s Thursday, September 12th. Joe O’Brien (known on the air as J.O.B.), whose square-jawed Irish punum now puts me in mind of the swabbies on McHale’s Navy, has the day off, and Ed Baer — “The Big Bad Baer” – is holding down his 6:00-to-10:00 morning drive slot. (The file only includes the first three hours of the shift.) It sounds like a lovely fall day, 62 degrees going up to the 70s, on what would have been the fourth day of the first week of public school — had the city’s teachers not gone on strike. (Actually, the 12th was the only day in two months that they were not on strike; they’d begun the walkout on Monday the 9th but ordered back to work, futilely, three days later. By Friday, they were gone till November. (Not to get too far off topic, some parents and kids crossed the picket lines and held “liberation schools” to provide us with some form of education in their absence. That was my introduction to high school.) Despite the likelihood that most of the station’s audience is home with nothing to do that morning, Baer makes no mention of the strike, although early on, after reading a commercial script for a furniture store in Yonkers that mentions “the kids are back in school,” he ad libs, “we hope.” (The every-half-hour news breaks, which must have addressed the city’s top story, are edited out, so I don’t know how the strike was covered.)

The show begins with a jingle singing “hello” in a variety of languages. With enough reverb to suggest an empty bank vault, Baer dives right in with Jeannie C. Reilly’s “Harper Valley PTA,” a clever blast of small-town turnaround loaded with sexy snark, sly innuendo (having a rhyme set up a likely line ending in “full of shit” but then using “hypocrites” instead), Dobro and y’all-type drawl. How amazing was it that this straight-up country song was a hit on a rock radio station in New York City, of all places. Despite the city’s sizable African-American population with Southern roots, a good portion of the station’s listeners probably knew little about that culture beyond what they’d seen on The Beverly Hillbillies (about to begin its seventh season as the tenth most popular show on TV), Green Acres, heading into its fourth, and The Andy Griffith Show, which had just wound up an eight-season run as the top-rated show on the air.) The song is sarcastic, sure, but its judgment remains within its local milieu, not of it.

Baer back-announces the song (radio jargon: ID the title and artist of a record after playing it) then tells a mild joke about the smallness of Harper Valley, with a blast of canned laughter (probably on a tape cartridge, pulled off a rack and stuck in a player by the show’s engineer). Then a (yikes!) cigarette commercial.

The Beach Boys’ pulsing “Do It Again,” currently number-16 on the station’s survey, is up next, followed by a commercial and O.C. Smith’s glacially paced, lushly arranged R&B-flavored “Little Green Apples,” already a much bigger hit than it was for the white Texan who cut it as more of a country song six months earlier. Baer enthuses about it in his introduction: “Glad to hear O.C. Smith’s version of the great Roger Miller song.” (A little credit please for the song’s writer, Bobby Russell.) It’s a sweet sentiment, sure, but who believes that small, sour fruit are one of God’s most notable creations, worthy of elevating in song?

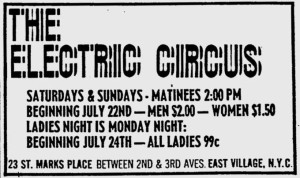

Baer reels off last night’s baseball scores then plays a lengthy jingle selling malt liquor (yikes again) and reads an ad for Barney’s, a popular clothing store on 7th Avenue and 17th Street then on its way to becoming a national brand, that includes a chance to win a pair of tickets to the Electric Circus. The fabled downtown discotheque had been the site of happenings by the Velvet Underground and the Fugs; by 1968, Cat Mother and the All-Nite Newsboys, a good-time outfit a lot less outré, was the house band. But it was still a crazy place. (Larry Packer of Cat Mother: “There was a room there called the foam rubber room, a dark room. I remember my aid being enlisted to carry an ODed dead body out of the foam rubber room. A young lady.”) So let’s imagine some random kid from Queens shopping for his bar mitzvah suit and winding up loose in one of the city’s hippest night spots as a result. Yay for commerce crossing the culture gap.

Speaking of gaps… Baer spins “Over You,” a song I barely remember by Gary Puckett and the Union Gap. “Lady Willpower” and “Woman, Woman,” sure. Ditto “Young Girl.” But this surging ballad doesn’t ring any bells. (Not that it has anything to do with my knowledge fail, it’s a really bad song, full of melodramatic swells, Bonanza-like strings, ridiculous lyrics and an abrupt melodic turn.) He notes that it was the previous week’s Sure Shot, probably an easy call after three consecutive Top 5 hits for the Civil War-garbed quintet.

An awful diet desert spot for the no-sugar gelatin Shimmer (rhymes with “slimmer”) precedes a surprising airplay selection: Status Quo’s psychedelic classic, “Pictures of Matchstick Men.” (Baer actually says the name correctly – STAY-tuss, not STAH-tuss.) The uncharacteristic song, which relegated one of the world’s most popular straight-up rock and roll bands from the ‘70s on to be a one-hit wonder in America, is a marvel of trippy lyrics, studio flanging and wah-wah guitar wash. (The title? Here’s one explanation.) Oddly, the second time I saw the band play in New York, at Irving Plaza in 1997, the audience was primarily Mexican; Quo was a big deal south of the border, capable of filling soccer stadiums and bullfighting rings there.

You might hear the Quo song as a museum piece, but it sounds a lot more relevant half a century later than the next number, Ray Stevens’ “Mr. Businessman.” (Are they programming alphabetically here?). The lyrics of this dated topical relic are something to behold.

Itemize the things you covet

As you squander through your life

Bigger cars, bigger houses

Term insurance for your wife

Tuesday evenings with your harlot

And on Wednesdays it’s your charlat-an

analyst

He’s high upon your list

Billboard once called Stevens “the #1 novelty recording artist of the past 30 years”; this one sits in his chart discography between “Harry the Hairy Ape” and “Gitarzan,” so it’s hard to tell if Stevens was truly despairing of the lifestyle damage done by capitalist business conformity, pointing a figure at a particular executive who wronged him or just stirring the soup, making it all up for provocative fun.

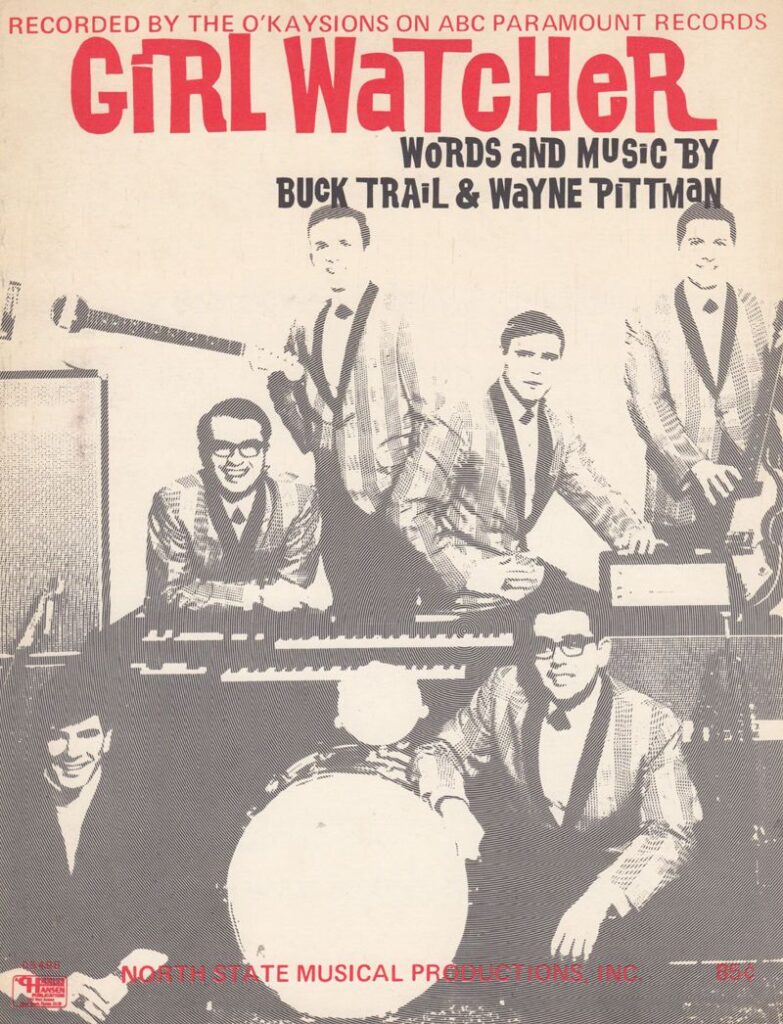

After a scoped-out news break with Herb Norman on the half-hour, Baer returns with groovy number-six on the weekly survey: “Girl Watcher” by the O’Kaysions. Based on sound alone, especially the singer’s honeyed melisma, I always imagined they were a soul group, but this sheet music snap makes the North Carolina outfit look like a suburban wedding band.

A later photo, however, has them in straight-up fake-hippie duds. (I guess they missed the summer of love by a few years.) Their lighthearted pop breeze, like a lot of the music on the station this day, has the peppy innocence of an arrangement for the Fifth Dimension, but that doesn’t hide the fact that it’s a leering ode to the harassment of women.

The basement makeout parties of my youth were redolent – at least in my dubious memory – of Wind Song perfume from Prince Matchabelli (for the ladies) and Hai Karate aftershave or cologne (for the men). The produced spot Baer introduces for the latter is a real wheeze: “A SPECIAL RADIO COURSE IN HOW TO MAKE SCARY-SOUNDING NOISES IN CASE YOUR GIRL LOSES HER HEAD OVER YOUR HAI KARATE.” (The insulting pseudo-Japanese gimmick, probably inspired by the martial arts on display in spy films starting with Goldfinger, promoted in shamelessly oversexed TV commercials, was that the aroma makes women lose control, wanton lust that must be fought off martial arts.) Baer riffs on the spot afterwards, weakly joking that karate lessons have made his hands such lethal weapons that he is afraid to applaud.

“1, 2, 3 Red Light” was the second of three million-sellers by New Jersey’s 1910 Fruitgum Company. While other successes of the genre were studio confections whipped up by Kasenetz and Katz or one of the era’s other Svengalis, these guys were – contrary to common belief – an actual band originally known as Jeckell and the Hydes and wrote some of their own material (if not their hits). Other than the scant, flimsy lyrics, it’s no worse than a lot of what was on the charts in 1968: well-produced, the mix emphasizing handclaps over than multi-voice lead singing and backing vocals. The key change comes out of nowhere and the whole thing is done in less than two minutes, even with a bridge that for a moment recalls a super-obscure personal favorite of mine, “Drop Everything and Run” (1966) by the mysterious Thane Russal.

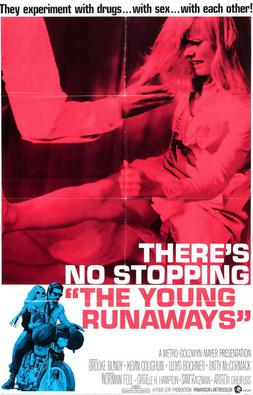

The hour’s second cigarette commercial (it would be another few years before tobacco products were banned from the airwaves) promotes one of Madison Avenue’s dumber slogans: “It’s not how long you make it, it’s how you make it long.” Baer gives the baseball scores again and then dives into a lengthy commercial break: Castro Convertible (I always wondered how the furniture manufacturer avoided being negatively impacted by sharing the name of the Cuban leader, an arch-villain to many Americans), orange juice, a dry-as-dirt PSA about environmental training for building superintendents, a weather check and a poorly produced spot for The Young Runaways, a lurid appeal to parents’ worst nightmares (or a likely guidebook for disaffected teens.) Perhaps the Ramones had this tagline in mind when they wrote “Cretin Hop” a few years later.

Then it’s back to the music with “Hey Jude,” the week’s number-one song (and one Beatles song I would be happy to never hear again). Baer plays six of its seven-plus minutes and enthuses “I love that” before throwing to a news break, again omitted from the MP3. (Another cigarette spot, this one read by newsman Steve Powers, is included.)

Baer’s traffic report leads into “Born to Be Wild,” the second single in a row to be a favorite on both AM and FM radio of the ‘60s. That MCA’s playlist could embrace country and bubblegum on one end all the way to what is now thought of as proto-metal on the other makes it a hallmark to the diversity that, at the time, didn’t seem like a concern to programmers. And certainly didn’t matter to listeners. Motown? Great! The Rolling Stones? You bet! The Mamas and the Papas? Love it! Frank Sinatra? Sure, why not. That situation would change very soon, but we certainly enjoyed it while it lasted.

The next spot Ed reads, for Blue Cross/Blue Shield medical insurance (not nearly as much a part of our lives then as it is now), is so rich with respect and praise for doctors that it could have been played during the 2020 pandemic. But what follows is one for the time capsule. From the “Community Bulletin Board” comes “a strange happening at the Architectural League’s gallery [on East 65th Street] this evening – people who go will be asked to step on to a scarlet acetate strip stretched around the block. The strip will then be cut into pieces, leaving people in various combinations. What happens will be a lesson in communication, behavior and participation. Sounds like fun.” And the next plug is for the showing of a Greta Garbo film in a church. Generation landslide!

Before getting back to the music, Baer plays a jolly jingle for a money lender (you try singing “the full amount you have in mind”), reads those baseball scores again, plays another cigarette spot (it’s terrifying how big a portion of the station’s advertising comes from the tobacco industry) and only then introduces “Down in the Boondocks,” Joe South’s proto-Marxist evocation of the impediments to inter-class romance recorded by Billy Joe Royal in 1965, as “a Good Guy goldie.” (Wikipedia notes that the song’s hook – a choppy, upcurled guitar figure — was copied from a 1963 Gene Pitney recording of the Bacharach-David composition “24 Hours From Tulsa.” Conicidentally, the O’Kaysions included a version on their Girl Watcher album.)

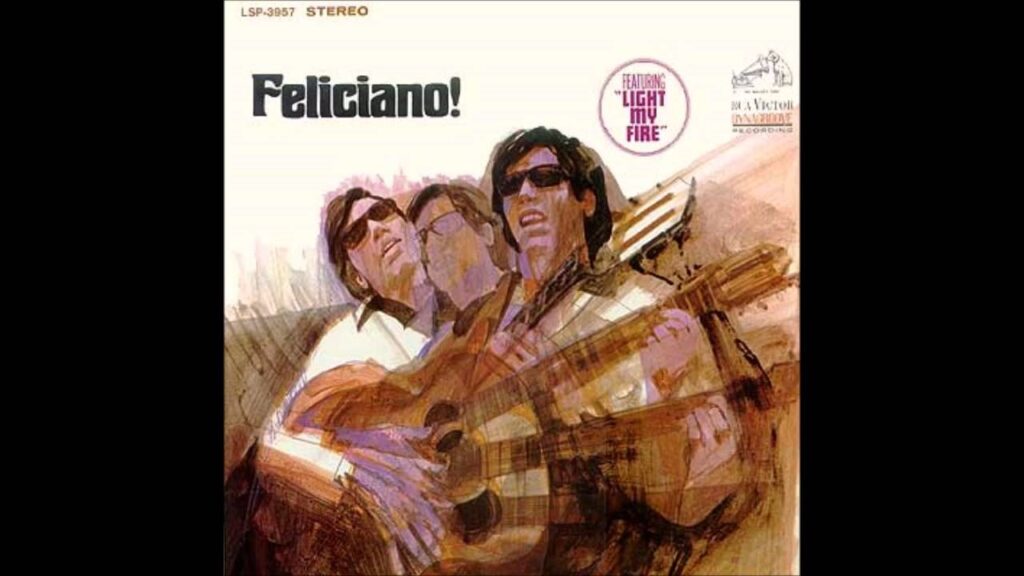

Coming up on the half-hour, Baer plays Jose Feliciano’s cover of “Light My Fire.” Blind, Puerto Rican, a virtuoso player of nylon-string guitar and a soulful, big-voiced singer, Feliciano occupied a strange position in pop – emerging from the Village basket scene, his youth (22 at the time), uniqueness and winning sincerity made him a popular entertainer but where other folkies – Richie Havens, for one – were warmly embraced by the incipient Woodstock nation, Feliciano tacked too hard to the mainstream to be considered hip. Yet, here he was, doing the nearly unthinkable by spinning the Doors’ year-old chart-topping signature song — a lusty roar of organ and near-psychedelia that, alongside “Born to Be Wild,” was as much a generational anthem as any — into a gently acoustic bossa nova, freestyling the lusty words into cheerful romance, erasing the image of a leather-trousered Adonis in the thrall of Bacchus and who knows what else. (Remember: there’s no stopping the young runaways!) Defanging Morrison’s horny creation, Feliciano made it appealing to a much wider audience and had nearly as big a hit with it. But his success was not without controversy.

A month after this spin on WMCA, Feliciano – again displaying his guts and artistic conviction — sang a reworked (what would now be called, cloyingly, “reimagined”) version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Tiger Stadium before Game 5 of the World Series and triggered (another modern coinage) racist blowback from “patriots” who objected to the funky, folky desecration of their beloved theme. “It was a disgrace, an insult,” baseball fan Arlene Raicevich of Detroit told the Associated Press. “I’m going to write my senator about it.” Bernie Gray, also from Detroit, said, “It sounded like a hippie was singing it.” Slugger Roger Maris of the St. Louis Cardinals told The Boston Globe, “I don’t think it was the proper place for that kind of treatment. Maybe I’m a conservative.” Pitcher Dick Hughes offered, “Thumbs down all the way. That’s a conformist’s song and should be sung the way it was written.”

Coming out of the AWOL news break, with no introduction or identification, the next voice you hear is Richard Nixon’s, accepting the Republican nomination for president a month earlier, calling for a reduction in U.S. foreign aid. Turns out it’s a campaign ad, one that sounds frighteningly like it could be airing today except that the words are actually coherent.

Nixon would not have appreciated the song that follows: “People Got to Be Free,” a wonderfully idealistic ‘60s sentiment that still sounds great. Pigeonholed as a singles band thanks to, duh, a run of really great singles, the Rascals never really got the respect they deserved at the time, although they worked hard to make strong albums. When they were still the Young Rascals, I saw them at a 1966 Murray the K Easter show at the Brooklyn Fox (also on the bill: Joe Tex, Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, Jay & the Americans, Little Anthony & the Imperials, Deon Jackson, the Shangri-Las, Patti LaBelle & the Bluebells, the Gentrys and the Royalettes. AM radio’s stylistic diversity in the flesh.)

A pain reliever ad, then a station medallion giveaway (Lisa Bellaran of Old Bridge, New Jersey: “you have 10 minutes to call PLaza-2 9944”). A quick Google search turned up the fact that she didn’t just send in postcards to radio stations, a few years later she was one of the kids who added their voices to Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out.” And she appeared on Broadway. Disappointingly, the aircheck does not reveal whether she called in or not.

A jingle oversells the benefits of chewing gum a bit, then – fucking hell! – another cigarette ad. On to the week’s Sure Shot, the Fifth Dimension’s “Sweet Blindness,” which oversells the benefits of drinking a bit. Laura Nyro was fighting to establish herself as a performer at the time, but her songs had no trouble rocketing up the charts for other artists. In fact, this is a somewhat slipshod rendition, with a giddy arrangement suitable for Love American Style and vocals that miss a few intended notes. (To be fair, Nyro’s own rushed, offhand rendition on Eli and the Thirteenth Confession doesn’t do the song justice, either.)

An Eastern Airlines ad unwisely bases its sales pitch on the variety of food served on flights (“Something Else”), and an Amoco spot promotes the relatively novel idea of plastic, urging customers to see America, “charge it all and take up to a year to pay.” (Which reminds me of The Man From the Diners’ Club, an wildly outdated 1963 comedy starring Danny Kaye as a company clerk who inadvertently issues a credit card to a mobster – Telly Savalas, no less – and has to retrieve it.) Which is still not as dated as the next song to hit the station turntable: “Shake Rattle and Roll,” the born-to-be-mild version by Bill Haley and His Comets. This surprising (for 1968) echo from the far end of the station’s oldies spectrum (1954) connects it to the dawn of rock and roll during an explosively progressive era that had already canonized sounds and styles unthinkable a decade earlier. Still, even while jettisoning a lot of the Eisenhower era and replacing it with protest marches hair, Afros and love beads, the youth of 1968 retained a measure of respect for certain blasts from the past: Chuck Berry was on a Fillmore East bill with the Who in June 1969, recognized as a father to the sons, and Sha Na Na, that slightly arch tribute band to music of the ‘50s, played Woodstock. Still, it’s amazing to me that no one who wasn’t meant to grasped what a “one-eyed cat peepin’ in a seafood store” signified.

A confusing ad for shoes sets up “Hush,” Deep Purple’s surging cover of the show’s second (!) Billy Joe Royal number written by Joe South. What are the chances of a heavy British rock band landing on a recent and relatively obscure American song (Royal’s version didn’t reach the Top 40 upon its release in 1967), putting it on their first album (where it joined renditions of “Help!” and “Hey Joe” and five originals) – and breaking big in America in the process? A similar tactic, which worked for Vanilla Fudge (“You Keep Me Hanging On”) that same summer, had been road tested a few years earlier by Otis Redding (“Satisfaction”). It’s hard to guess whether such cross-pollination fed into radio’s diversity at the time or was a way to game the system, getting a song back on the air in a new style. This wasn’t Pat Boone deracinating R&B for an isolated audience, this was musicians bringing what they liked to an otherwise unfamiliar audience, much as Cream was able to popularize the work of Robert Johnson.

The final hour of the show repeats the 6:00 am sign-on, includes a more detailed traffic report and then, perhaps staying on that topic, gives “1, 2, 3 Red Light” another spin. I remember once being home from school, sick in bed, and being shocked and disappointed during a long day’s listening at how often the week’s hits were repeated. But I don’t remember ever hearing a creepy Excedrin commercial that (a) claims to contain an anti-depressant (what, caffeine?) and (b) advises women suffering from menstrual cramps to wash their hair or try on lipstick to feel better.

Another thing I don’t remember is the crossover success of Sergio Mendes’ easy-listening take on Paul McCartney’s “Fool on the Hill,” sung by Herb Alpert’s missus, Lani Hall, which reached number-six in Billboard that summer. Beatles covers were common as muck in the ‘60s – everyone wanted to ride their coattails with sure-fire songs – and tried them in every possible style, frequently glossing over the subject matter as if it didn’t matter. (Like this one.) The Beatles included the song on Magical Mystery Tour; it was never a single for them, still the royalties rolled in.

Baer follows a somber commercial — Nikoban lozenges “for real help in breaking the cigarette habit” – with a flip (and probably inadvisable) joke, gives the ball scores one more time, whips off a dumb one-liner about sports and then digs out another golden oldie, this one from 1958: Bobby Darin’s “Splish Splash,” good clean (ahem) fun just short of being a novelty record. In time’s telescope, the difference of a decade after a half-century feels far less pronounced, but I imagine the generational gulf between some of the songs played on this show must have felt huge. Like a lot of the listening audience, I was a young teenager at the time, so that song was a hit years before I started listening to the radio and – unless it got regular airplay — was probably unfamiliar to a lot of us. “Mack the Knife” was ubiquitous, so I expect I knew Darin’s name, although I was not aware I was beginning my high school education at his alma mater.

Continuing the crass promotion of unhealthy products, a Tastykakes spot targeting kids stakes a dubious claim to “nutritional value.” But then on to something of real value: the Equals’ “Baby Come Back.” The tremendously exciting bi-racial English/Caribbean band, whose lead singer would score a much bigger solo hit 15 years later with “Electric Avenue” (yep, Eddy Grant), was also the originator of “Police on My Back,” which the Clash covered to fine effect on Sandinista!, and loads of other great stompers like “Michael and the Slipper Tree,” “Green Light,” “Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys,” “Softly Softly” and “Rub a Dub Dub,” a sexier version of “Splish Splash.” I highly recommend the Viva Equals! compilation; no music collection should be without a decent collection of their work.

Baer sounds like he’s suppressing a chuckle during his pitch for Gerber baby food, but that’s forgotten when he plays the week’s number-ten song, Marvin and Tammi doing “You’re All I Need to Get By.” My favorite Ashford and Simpson production and composition, it’s simple, short (2:38, although here it’s faded out under Baer’s praise around 2:18) and sung with bountiful heart and soul, rising from an intimate declaration to a glorious testimony, and then repeating the ride again. It’s still so spine-tingly fine all these years later and heartbreaking to think that she died, 24 years young, less than two years later. Few singers ever delivered a better performance than she does here.

Another awful cigarette spot, a news break, and then – before another shoe spot – a passionate Bill Medley single, “Brown Eyed Woman” (written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil; no patch on Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” from the previous year). He had recently broken up the Righteous Brothers and was struggling to rekindle the duo’s success on his own. He never really did, and reunited with Bobby Hatfield in the mid-‘70s.

Wrapping up the third hour, coming up to 9:00 am, Baer reads a spot for the start of horse racing season at Belmont Park and then gives the week’s top song, “Hey Jude,” its second spin of the morning. And that’s where the MP3 ends.

MCA changed to talk-radio in 1970; you could say the 1960s ended there for a lot of us. Truth be told, I’d already switched over to FM, mainly WNEW-FM, and looked down my nose at the hype and tight playlists of my former sanctuary. Baer died in January 2019; he was 82.