This extraordinary piece of on-site reporting was originally published in Trouser Press Collectors’ Magazine issue 27 (January/February 1983).

By T. Joseph McGrath

His room is quiet now. The bed is neatly made. A picture of a rough-and-tumble sea storm is framed over the bed. His old school desk, complete with coffee stain and pen, is pressed against a far wall. Volumes of Chaucer, Blake, Flaubert and Shakespeare peer down from a corner bookshelf. An old-fashioned radio sits ready and lonesome. His shirts are carefully folded in the dresser, his black sports coat hangs loosely in the closet.

Nick Drake’s songs cast an eerie spell on first-time listeners. It’s not only that he produced some of the finest melodies and lyrics ever to grace the spiral grooves of a record, or that he worked with some of the best musicians in the business, or that he influenced many a romantic young man to take up the art of song. It’s the emotional intensity and the sincerity of his music that makes me want to play the songs of Nick Drake over and over again.

Drake was an original, a man who dared to throw his hat to the wind. Uncompromising and strong-willed, he had a vision of how each of his songs should be presented. Those songs remain to spin the story of his life. Delicate and fragile slices of experience, they are meant to tease and bewitch listeners – little shadows dancing on a pink moon in the northern sky.

South of Birmingham, in the West Midlands of England, Far Leys is a comfortable brick house at the end of a tree-lined cul de sac. It is a warm and charming retreat. The rooms are painted in subdued swirls of yellow and blue. The grounds are lovely: carefully tended flower gardens and walkways that overlook a sweeping view of the distant hills. Far Leys is the house where Nick Drake grew up, and where he spent his final hours.

Nick’s parents, Rodney and Molly Drake, still live at Far Leys. They accept the occasional late-night phone call from fans as part of his legacy. They welcome tourists with open arms. Young and old, Nick Drake purists arrive sometimes without warning — in crippled vans, smart roadsters, even on foot. They come knocking at Far Leys and they come looking for Nick.

His parents enjoy the attention Nick is getting nowadays because he never received much while he was alive. His albums sold poorly, his concerts were sparsely attended and he thought of giving up music many times. In the U.S., David Geffen was captured by his music and expressed interest to Island Records; Island said no thanks and Drake remained an English obscurity. Some say that contributed to the awful bouts of depression and melancholy that tormented him. In any case, he felt his music was beyond the reach of many. Only after his death did his parents understand. Nick’s music enchants and enthralls; the spell cannot be broken.

Rodney Drake is a tall, handsome, articulate gentleman who has spent some time traveling around the world on behalf of a British lumber firm. In the early 1940s, he met and married Molly, an aspiring singer and songwriter, and together they left England to live in the Far East. It was in Burma in June 1948 that Nick Drake was born. Two years later the Drake clan (including Gabriella, Nick’s elder sister) returned to the British Isles and settled in the sleepy English hamlet of Tanworth-in-Arden, a stone’s throw from Stratford-on-Avon. It was there, in the large and snug house called Far Leys, that Nick first displayed his talent.

“As a baby he loved to conduct,” recalls Molly. “Whenever the music started, he would be up out of the chair waving his hands. I think, at one time, he had an ambition to become a famous conductor. He dearly loved classical music and listened to it all the time.” Rodney chimes in. “He picked up on the piano quite early and was rather good. He was fascinated with some of the legends and myths incorporated into classical pieces. He loved a good story, even if some of them scared him half to death.”

After attending local primary schools, Nick was shipped off to Marlborough, an upper-crust private school that prepares boys for entrance to top-notch universities. There Nick distinguished himself by winning several awards in track and field (his record for the 100-yard dash still stands) and playing clarinet and saxophone in the school orchestra. He also showed a keen interest in folk and rock music, especially the Beatles. He begged his parents for the funds to purchase a guitar. They finally relented, sure that this new instrument wouldn’t last long and that he’d soon be back on the old piano. Nick rushed out to buy himself an acoustic six-string at a local shop and enthusiastically plunged into learning how to play. According to his parents and friends, he became skilled within months. After only a year, he was performing at private parties and functions. The piano was left to gather dust.

Nick could listen to a song once and then repeat it from memory. This gift allowed him to practice advanced folk guitar techniques such as open tunings, double-pick rhythms and two-finger rolls. John Renbourn, Bert Jansch, Davey Graham and Joni Mitchell were a few early influences. Around this time he was also developing his own singing style, a blend of twisted syllables and slurred consonants. That became the Nick Drake trademark: cool, distanced phrasing with just the right touch of timing. Some critics contend that he sounds as if he were singing on the moon. Ethereal and angelic, his voice seems to float over the instrumentation.

Nick made many tapes right before he left Marlborough. His favorite spot for practicing and recording was an orange armchair, and he used to lounge around for hours at night slumped in that chair working on chord progressions and tunings. While working on new songs, he often never slept. “I used to hear him bumping around at all hours.” Molly Drake says. “He was an insomniac. I think he wrote his nicest melodies in the early-morning hours.”

These early tapes also reveal Nick’s penchant for choosing the desolate and disturbing themes that mark just about all of his later work. Many of the songs tell of defeated love and heartbreak, while others dwell on alienation and the dark shadows of loneliness. An ability to interpret other people’s songs and make them his own is evident in numbers like “Blues Run the Game” and “Summertime.” Such originals as “Princess of the Sand” and “Joey” are romantic odes to lost youth, beautiful in their simplicity and intent but also uncommonly sad.

Rodney Drake owns these tapes and be plays them for visitors. “Nick recorded them right here in the sitting room on a primitive tape recorder. He was quite a perfectionist and was always erasing songs that he deemed inferior. I managed to grab a handful of tapes one day before he found out.” The Nick Drake Cassette is a collection of these tapes. Even with the poor sound quality and the occasional hum and hiss, the music is a cut above your average folk album. Perhaps one day Island Records will see fit to clean up these tapes and release them to the public.

Nick left Marlborough for Fitzwilliams College, Cambridge. He was accepted as a scholarship student in English. He read voraciously, taking special interest in the poems of William Blake. Blake’s view of the world as heaven or hell corresponded with Nick’s private feelings. Blake took refuge in his woodcuts; Nick concentrated on playing guitar.

Nick performed often. His gigs included proper charity balls and coffeehouses. He was playing at the Roundhouse, a favorite Cambridge haunt, when Fairport Convention co-founder Ashley “Tyger” Hutchings spotted him and brought him to the attention of Joe Boyd the American producer who had a company called Witchseason Productions. Hutchings thought Nick an outstanding talent. Boyd, after listening to Nick’s audition tapes, agreed. The 20-year-old was given a contract and sent into a recording studio. It was all happening too quickly, says his mother. Nick wasn’t prepared.

Boyd, whose production credits included early Pink Floyd, Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band, says, “I’ve always had a strong taste for melody, and it has obviously been reflected in the people I have worked with. And it was Nick’s melodies that impressed me. There was also a sophistication and maturity about his songs and the way they were delivered. I really did feel that I was listening to a remarkably original singer.”

After one arranger was sacked because he felt that his songs “weren’t getting through,” Nick brought in a Cambridge friend, Robert Kirby, to help. Kirby, who had no previous studio experience, was looked upon with skepticism by Boyd until he heard the finished tape and was delighted.

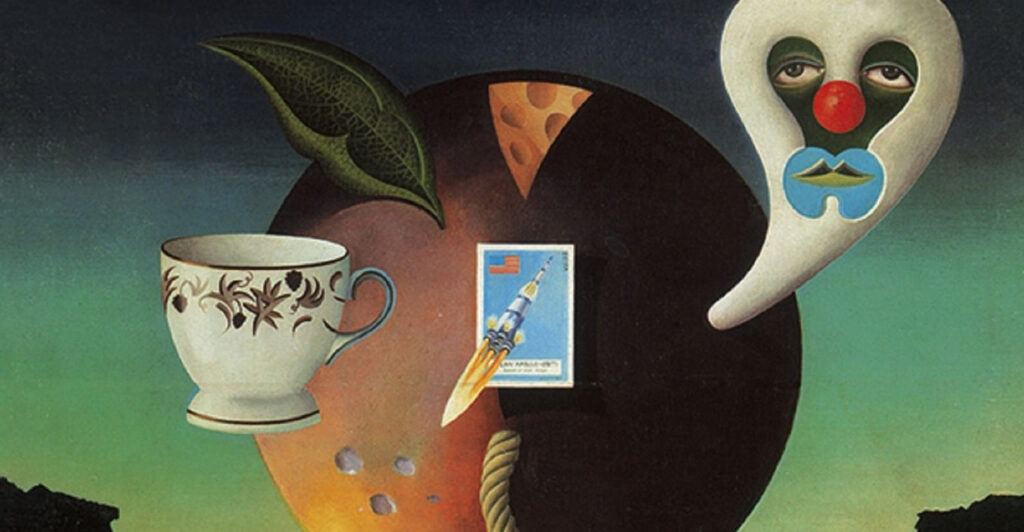

The title of Nick’s first album, Five Leaves Left, refers to the warning sign printed on a package of cigarette papers. When you’re down to five it’s time to buy some more. Nick thought it an excellent title, though it lacked any particular significance at the time. Now it seems like a prophetic hint of transience. The album jacket shows a pensive Nick staring out of an attic window at some object a long way off. He is dressed in a favorite black sport coat that always looked a bit too tight.

Whimsical at times, with just the right touch of English melancholy, Five Leaves Left is an anthem to grand dreams and desires unrealized. “Time Has Told Me” sets the tone for the entire album with its hauntingly world-weary bluesy melody. The song is subtly startling in its eclecticism: a cozy piano tinkling country-and-western fills; Richard Thompson’s rock-guitar trills, Drake’s own folk-guitar chording, and his mixture of blues and jazz vocal inflections.

“River Man” promises a stark look at spiritualism: “Going to see the River Man, going to tell him all I can…. I don’t suppose it’s meant for me. … Oh, how they come and go.” The lyrics weave through Harry Robinson’s swirling strings, as though the listener were set adrift in a small boat down some forgotten river of time. “Three Hours” develops the theme of the eternal seeker with its low African drums, driving bass, and murky vocal. The story revolves around a London lad named Jacomo going “down to a cave / In search of a master / In search of a slave.” False paths and false starts can only lead to more searching, Nick tries to explain, but enlightenment is elusive.

“Day Is Done” and “Way to Blue” are perfect vehicles for Kirby’s lush and melodic string arrangements. Kirby recalls that Nick’s songs were introspective to the point of being morose. “Nick was remarkable for his ability to observe. I see his work as a series of extremely vivid, complete observations, almost like little epigrammatic proverbs. The music and the words are welded together to make atmosphere the most important facet.”

The rest of Five Leaves Left demonstrates just how much “atmosphere” Nick Drake was capable of producing. “Cello Song” is a rich meditation on leaving things behind forever. “Saturday Sun” and “Man in a Shed” are quirky little jazz-flavored pieces. The most telling piece, however, is “Fruit Tree” — a song that Molly Drake adores. It seems to be autobiographical, outlining the fragile beauty of fame and how it lies just out of reach. It also seems to sum up the direction in which Nick was traveling:

Safe in the womb

Of an everlasting night

You find the darkness can

Give the brightest light

Safe in your place deep in the earth

That’s when they’ll know what you’re really worth

Forgotten while you’re here

Island Records, which bought Boyd’s Witchseason company in 1970, was enthusiastic about but bewildered by Drake. The company had no idea on how to market him. One of its press releases at that time screams confusion: “Nick Drake is tall and lean. He lives somewhere close to the university… because he hates wasting time traveling, (he) does not have a telephone more for reasons of finance than any anti-social feelings and tends to disappear for three or four days at a time, when he is writing, but above all… he makes music.”

Critics enjoyed Five Leaves Left but sales were disappointing. Nick was taken back a bit by the chilly reception. He was having a hard time performing his private songs in public now. A gig with Fairport Convention at the Royal Festival Hall proved frustrating; a tour of eight clubs in the north country was a disaster. Nick Drake gave up touring forever.

But he wanted to try recording again. He enlisted Robert Kirby to again handle the bass and string arrangements. He hired Richard Thompson, Dave Mattacks and Dave Pegg (all from Fairport Convention) to help out on, respectively, lead guitar, drums and bass. He asked John Cale to sit in on viola and celesta. He found Chris McGregor and Ray Warleigh playing at local jazz clubs and brought them in. Pat (PP) Arnold and Doris Troy, two highly respected backup singers, were asked to join the sessions. His next album, according to Nick, was going to be his saving grace.

Bryter Layter is in many respects a flawless album. Joe Boyd and John Wood, Nick’s engineer, both call it a masterpiece. Wood found him determined to come up with a winner. If anything can be said about Bryter Layter it is that the album is chock-full of good intentions — and sad intentions. “Introduction” is a taste of things to come with its gloomy strings and soaring bass lines. “Hazey Jane II” and “At the Chime of a City Clock” explore urban life among strangers. “Hazey Jane” stops the show. Nick’s voice has never been filled with such wonder as he asks: “Do you curse where you come from? / Do you swear in the night? / Will it mean much to you If I treat you right?” Also noteworthy is “Northern Sky,” one of prettiest love songs ever recorded. It is not just love Nick is after but acceptance. The imagery is blinding in the little word dances that accompany the melody. Again, sadly, Nick is reaching out for something that he knows he’ll never get.

After Bryter Layter, Nick’s growing disenchantment with his music and his life reached an all-time high. With few close friends and his new album wallowing in obscurity, Nick closed the door. He took to living at home at Far Leys, spending hours looking up at the sky. For some reason, Nick felt he had failed his family and friends and took that imagined failure to heart. Island Records gave up on Nick Drake ever be coming a big-selling folk artist, though it did not drop him from the roster. Joe Boyd was off in the United States, racking up hits for Maria Muldaur. It looked like Drake’s career was over.

But Nick pulled himself together and gave it a final go. He contacted John Wood to reserve some hours in a recording studio and arrived guitar in hand. Pink Moon was recorded in two days. Nick was so depressed during the recording that he barely spoke two words to Wood. At one point Wood asked Drake what was wrong. Nick just mumbled something and walked away. The tunes took a heavy toll on him; you can hear it in the music. The songs are stripped to bare emotion. No lighthearted and melancholy verses — these songs are cloaked in despair. Wood says Nick was adamant about what he wanted — just voice and guitar. At first, Wood thought Drake was planning to use these takes as demos for future sessions. Then it dawned on him that Nick wanted the songs released exactly as recorded: stark and spare. Pink Moon gives no quarter.

Connor McKnight wrote in Zigzag, “Nick Drake is an artist who never fakes… [his) mood is reflected in the album. Without the arrangements, and with (printed] lyrics for the first time, it is impossible to avoid the seering [sic] sensibility behind the record. The album makes no concession to the theory that music should be escapist. It’s simply one musician’s view of life at the time, and you can’t ask for more than that.”

Pink Moon is a brittle collection. Robert Kirby has said that it’s his favorite because, “Nick pushed himself. He was an absolutely phenomenal guitarist, a fact which is all too often glossed over.” His best playing can be heard on “Things Behind the Sun” and “Free Ride.” His guitar at times goes into a frenzy, chopping off notes and bending others to the breaking point. The tuning has puzzled many a professional musician, too, and Mr. and Mrs. Drake get monthly inquiries from all over asking if they’ll send out Nick’s tuning pattern. Of course, they have no idea. “He kept it all in his head,” Rodney explains.

The message behind the songs is clear. “Now I’m darker than the deepest sea / Just hand me down / Give me a place to be” — these lines from “Place to Be” spell it out. Nick was in desperate trouble. His pleas for help also surface in “Parasite”: “Take a look you may see me on the ground / For I am the parasite of this town.” But no song is more troubled than “Know”: “Know that I love you / Know I don’t care / Know that I see you / Know I’m not there.” Nick’s ghosts were closing in fast.

After Pink Moon, Nick retreated to Far Leys. He refused to see his old friends or talk to anybody. He just sat in that old orange armchair and looked off into space. His parents tried to seek professional help and doctors prescribed antidepressant pills; it was no use. Nick was gone.

He roused himself long enough to venture into the recording studio one last time in 1974. The four songs tha he recorded can be found on the Fruit Tree compilation. They are ragged and uneven but give some insight into Nick’s private hell. “Black Dog” tells of being chased by a supernatural beast. “Hanging on a Star” reaffirms Nick’s view that all hope was lost and that his life was one big failure. To call these songs “depressing” would be kind.

Nick was down and out, but not yet finished. He took off for France in October 1974 and lived on a barge for a while. He contacted French singer Francoise Hardy, who had once expressed interest in recording an album of Nick’s songs. He arrived back at Far Leys confident that he had finally found some sort of direction.

But life plays cruel jokes. On November 24, 1974, he was up and about as usual at night, planning and writing songs. Nick still had trouble falling asleep and his parents were quite used to him pacing the floor. He had a Brandenburg Concerto on the turntable. His mother recalls him going into the kitchen for a midnight snack of cornflakes. “I usually would wake up and join him at the table. For some silly reason, that night, I rolled over and went back to sleep.” Nick’s insomnia was bothering him. He picked up a bottle of Tryptizol, his antidepressant pills, and thinking they were sleeping tablets, took an accidental overdose. His mother found him dead in his bed the next day. The beasts were silent at last.

Nick lies buried in a Tanworth-in-Arden churchyard, his crumbling gravestone overlooking a wide expanse of closely cropped hills and carefully tended meadows. It is a good view. [His parents are now buried there as well.]

Inside the church next to the cemetery is a magnificent pipe organ which is used to accompany the church choir. Above one of the organ stops is a brass plaque with Nick’s name on it. His father and mother donated the necessary money to keep the church organ going strong. Once a year, the church organist plans a special recital of Nick Drake’s songs. The church is packed, and the townspeople lift up their voices to pay tribute to a native son. They say you can hear the singing for miles around. Nick would have liked that.