By Ira Robbins

I have never understood the appeal of ingesting information by being talked at. It didn’t work in school (show me the book, I’ll take it from there), and I don’t find listening to podcasts all that enticing. It’s never even crossed my mind to listen to an audiobook for fun. (I’ve created a few, so I’ve endured some of those, but it wasn’t fun.) But as an old fan of the Jesus and Mary Chain, I very much wanted to read Never Understood, the memoir by William and Jim Reid published last year. I have recently discovered that reading books on a phone is weirdly convenient, so I reserved a digital copy via the Libby library app. A few weeks later, I was unpleasantly surprised to realize I had inadvertently borrowed the audiobook. What am I supposed to do with this?

But once I saw who the narrators were, I thought I’d give it a try. Within moments, I was hooked. In Jim’s sonorous and deliberately paced and dapper Scottish/English voice and William’s syncopated (and less easily understood) working-class brogue, the effect is not of a book being read aloud, but of two enormously likable fellows alternately recounting their shared life story for nine mesmerizing hours. It’s weirdly intimate, almost as if they’re speaking directly to you. And with colorful inflections. It’s fucking brilliant.

Like most rock memoirs, the usual elements appear in logical sequence: the pre-story (growing up poor in Glasgow and East Kilbride in an extended alcoholic family), discovering music (the Beatles, T. Rex, the Velvet Underground, Stooges, Sex Pistols, Subway Sect), the formation of the band (which hysterically hinges on a fuzz pedal bought off a pal and a Portastudio purchased using money their dad gave them out of the severance he got losing his factory job: “You bought a tape recorder?”), the sequence of nearly random occurrences that led to them getting signed and finding stardom. There are the obligatory record company travails, personal conflicts, touring miseries, drink, drugs, lineup and manager changes, lunatic experiences and the lot. The band eventually breaks up, the Reids get sober, get back together (aided by a recording project with their kid sister Linda) and the band ends with the satisfaction of fatherhood, contentment and comfort.

But this is the Jesus and Mary Chain, not some boring pop band. There are flashes of offbeat wisdom. Admitting to an adolescent gambit of collecting protection money from drivers of parked cars, William offers: “We were like FOX News, exaggerating the threat level for material gain.” They both do deep analysis of the cause and effects of drug-taking. Jim: “Acid makes whatever you’re listening to sound amazing and profound. You might as well just switch off the tape machine and listen to the birdsong. When you’re on acid … you can hear what [the birds] are saying, you just don’t remember it when the drug wears off.” The Reids’ story is rich with childhood memories of family and friends, the Rangers F.C. (William follows the football, Jim can’t be arsed), surprisingly broad and literate cultural references (Proust and Jack Kerouac, Star Wars and Lindsay Anderson’ If, The Young Ones and Seinfeld; the scope of their musical knowledge is likewise impressive), catastrophic self-sabotage and chronic social anxiety. Jim recalls being on tour in Chile with R.E.M. the night of Barack Obama’s 2008 election and passing on an invitation to watch history being made with his highly regarded tourmates. “The thought of sitting around with all these famous people I didn’t know was too much for me.”

William: “I think we were meant for some weird outlier version of celebrity where we were too shy for people to actually look at us.” That abiding self-consciousness, reticence and insecurity are at the heart of the story and supply one explanation for years of inexplicable (if not inexcusable) behavior, excessive drinking and drug abuse. Jim asserts repeatedly that the thought of getting up in front of people – even as a big star – felt so awkward that he didn’t perform sober for decades. (“Left to my own devices, I struggled with going outside my own house … but with the help of booze and drugs, all things were possible.”) There are anecdotes about meeting idols (even the Ramones!) and being unable to interact with them, a reluctance Jim attributes to his own discomfort at being the object of fandom. There’s an especially regrettable encounter with Iggy Pop after his crew prevents the Reids from doing a proper soundcheck. William describes sitting miserably in dressing rooms with musicians he admires but is unable to engage with. In a segment on lifetimes of untreated depression, his own and others’ — he wonders why Kurt Cobain didn’t just buy himself an island and get away from the spotlight he loathed — William recalls bailing on a much-needed session with an NHS psychiatrist because he reckoned the shrink knew who he was. While Jim comes off as droll and deadpan, a wry and witty observer of the life he’s lived, William’s toughness, bluntness and occasionally eccentric impulses (reclaiming an answering machine he’d bought McGee) make him the more compelling character here: his focus on the band’s creative work is welcome, and a memory of turning their mother on to pot is funny. But the consistent throughline of the book is the blend of insecurity, stubbornness, iconoclasm and self-belief that drove the band to success, to failure and to drink.

Not surprisingly, the Reids have strong opinions about many things, few of them (other than rock bands and friends) especially favorable. Spandau Ballet is an icon of musical awfulness for Jim, and their feelings about rock critics stings a bit, but in aggregate the ire was probably well-earned. Alan McGee, who was instrumental in giving the band its start and put them on his Creation label, comes in for criticism as a wannabe Malcolm McLaren, but they still got him back as their manager decades later. Geoff Travis of Rough Trade is a pal and ally until suddenly he isn’t, a break that still seems incomprehensible to them. American record man Jerry Jaffee, who managed the band for a minute, is fondly noted, complete with Jim’s vocal impression for effect. (They both do that a lot here, and it’s reliably funny to hear the imitations of gruff Scotsmen, clueless Americans and each other.) Rob Dickins of Warner Bros., one of the “Armani suit guys” towards whom Jim holds burning animosity, gets a modicum of respect for telling them the truth, even when the truth is that he hates an album they’ve delivered. That’s one of the moments when the Reids’ surprise at the ill results of their twisted careerism feels disingenuous (or self-deluding), but they never would have made such thrilling music had they done what people expected of them. There’s a fine line between courageous trailblazing and setting yourself on fire.

As William says early in the book, “Being young is mental and brilliant. And that’s why most great music, unless you’re talking about people like Paul McCartney or Bob Dylan who seem to be able to do it forever, is made by brilliant, mental young people.” It’s the rare creative genius who can make a big splash early and then find a whole new recipe for magic decades down the road. The balancing act of repetition and innovation, especially as perceived by longtime fans, rarely leads anywhere great. In fact, the Reids make it clear here that, after the monumental achievement of the fuzzed-out-echo-drenched Psychocandy, their iconoclastic instinct was to never make another album like that. They had a great run in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but they haven’t added much to their legacy since then. Honestly, I’d rather relisten to this book than spend a second hour with last year’s Glasgow Eyes.

For a band of self-declared misfits who hide behind shades, have never been that keen on doing interviews and never evinced much concern for their public image or business dealings, the self-awareness, insight and revelations here are shockingly generous: part prideful explanation, part rueful confession. Amid the wild tales, fun facts, flashes of bitterness, genial criticisms of colleagues (and each other), both men express remorse about things that did or didn’t happen and resentment about some things that did. They admit to mistakes and jealousies, push back against unwarranted accusations and appraise each other with care and love. There’s a bit of score-settling, but not to the degree that it sours the story or makes the Reids seem petty. They really seem to have a firm grasp not just on what they did, but why they did a lot of it, for better and worse, with a measure of candor that feels deeply real. No doubt there are elisions and distortions, unfounded memories and misplaced antagonisms here, but I can imagine no better explanation of who they are and how they came to make a huge dent in the rock world in the 1980s.

How Ben Thompson, the Reids’ collaborator on the book, got them to put all this down on paper and then voice it as beautifully as they have should have been included as an epilogue. William lives in Arizona, and Jim is settled in Devon, in England’s southwest. The logistics must have been many, and there are a few spots where the editing seams show. But hats off for the editorial prowess that juxtaposes one’s specific memory with the other’s immediate correction. When the brothers, who once thought of themselves as Siamese twins with closely shared opinions, taste and values, get to the point of not speaking to each other, William offers more analysis of the hows (a bowl of macadamia nuts and a keyboard solo, as it turns out) and whys. And he gets the final word, as befits the elder sibling.

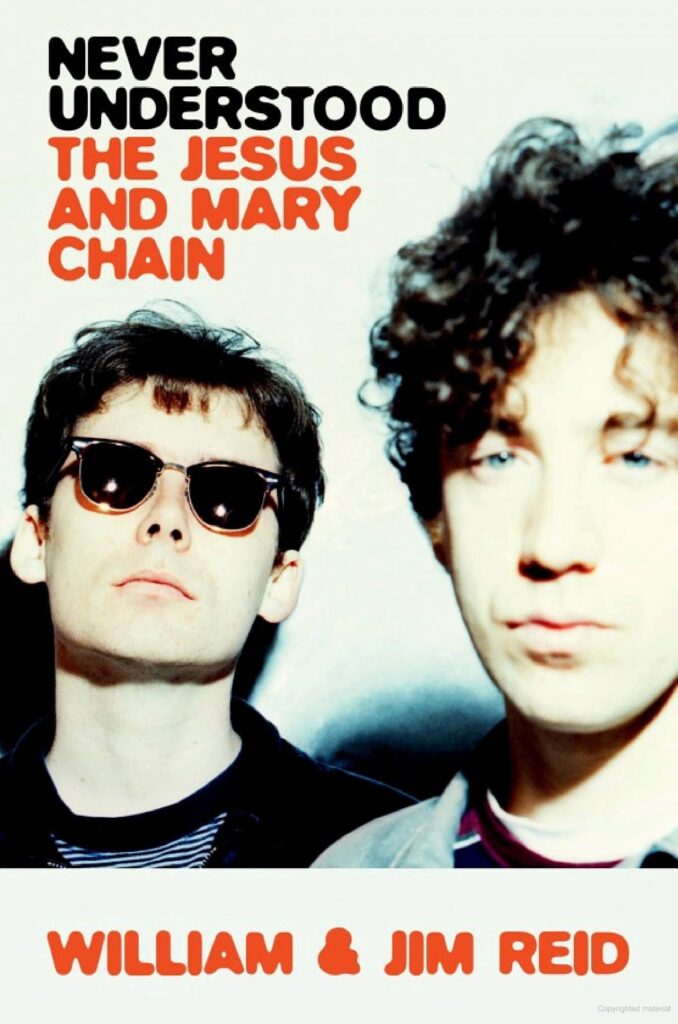

The Reids are no longer young, brilliant and mental. They are in their sixties (not that you can tell that from listening to them here – my mental image remains the young and stylishly rumpled twenty-somethings of Psychocandy) and reasonably well settled into comfortable lives that seem to be about family as much as making music. That they are here proven capable of not only documenting their lives but recounting them with such audible pleasure is a wonderful coda to the music they have gifted the world.