This is excerpted from Music in a Word, the first volume of a memoir and anthology by Ira Robbins. Available as an E-book here.

By Ira Robbins

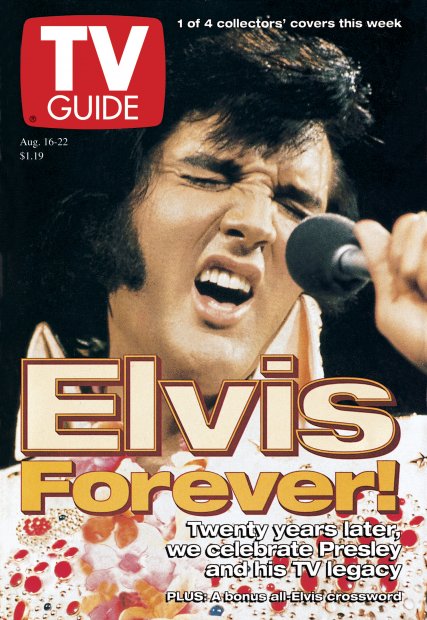

After we worked together at Newsday, Lois Draegin, an excellent entertainment editor, moved on to TV Guide and, in 1997, called on me to do a piece for an “Elvis 20 Years Dead” issue. The gig paid well and was in a magazine I’d grown up reading and really — at one time, at least — admired. (I still have a box of old Fall Preview issues in the cellar somewhere — I loved seeing what ridiculous fare the networks had in store for America.)

My job was a quick oral history of the handful of TV hosts who’d presented Elvis early in his career. Which, amazingly enough, meant getting on the phone to interview Steve Allen, Wink Martindale, Jimmy Dean and the nearly 89-year-old Milton Berle.

This was a strange experience. Berle was a legend, a figure so engrained in American culture and yet so far outside my cultural world that talking to him on the phone didn’t quite feel real. When I called, some servant answered, which already put me in the mood of a Nick and Nora picture. I can only imagine the mansion he inhabited. Berle was old and hard of hearing, but completely capable of reeling off ancient anecdotes.

I suppose he might have been the most famous person I have ever interviewed. I didn’t have to ask too many questions. And his signoff left me staring at the phone in amused disbelief.

Milton Berle, 21 May 1997

“I was on the air since ’48 when I started the Texaco show. I’ve been with the William Morris Agency 65 years. Lastfogel, who was the president of the company, was approached by Colonel Tom Parker. Lastfogel spoke to me. He said that Tom Parker has this young fellow, Elvis Presley. Lastfogel, who was my agent, asked would I consider putting this young fellow on? It was Parker who got in touch with the Morris office. He was the backbone of the kid, of Elvis. I said, can I see him, can I hear him? So they gave me an audition.

“They brought him to me. I saw him, and I heard him, and I said fine. I had been on television a long time, from ’48 on, but this happened in ’56. At that time, I had specials, and I put him on a special, and I remember who was on the special that I had booked. I had Harry James’ Orchestra (Joe Williams was singing), Esther Williams and this young fellow that was referred to me by Lastfogel. Parker was his manager.

“We did it from the deck of the Hancock in San Diego. When he showed up, I had him picked up in the car from the airport. I did four big specials in addition to my show, and he was on one of them.

“At the drums of Harry James’ Orchestra — and he’s gone, may he rest in peace — that’s Buddy Rich playing the drums.

“He came in, we picked him up, and he was with Parker. I picked him up in the car, personally, in the limo. Now we’re driving back, and he was very charming, he was cute, he was very adorable, very shy, and very good looking and very soft-spoken. He was very nice. Col. Parker, who I knew before he had Elvis, I did medicine shows for him in the ’40s. He was very sharp and worked very hard, and very bright.

“Anyway, coming back in the car over to the boat, Elvis said, ‘Very pleased to meet you Mr. Berle, I watch you on the television,’ like a young fan. I was very nice to him, I think. I must have been. The three of us are riding in the back seat of the limo toward the ship and I had the contract for his appearance in my pocket, we’re talking and I opened the contract with the three of us sitting back there and Parker grabbed it away from me. He said ‘Don’t show that contract to the boy!’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know that, Tom.’ I don’t think he wanted Elvis to see the contract that Elvis was supposed to sign. He kept everything away from the boy. He was taking care of Elvis. He wasn’t cheating him, but he didn’t want him to know… ‘I’m the boy’s manager, just let me see it.’ It was Parker that really worked on him, public relation wise, put him on the right track and all that. Parker deserves so much credit.

“The first time there on the boat, we did the rehearsal. We had the band and everything and we had put little folding chairs on the boat for an audience. I remember I did this with Sinatra back in ’43, when he opened at the Paramount. We loaded the audience with young people so when we got to San Diego, I told my assistant — who was George Schlatter by the way, he’s a big producer — I want you to round up three or four buses and go over to the high schools and get me a lot of girl students and bring ’em over to the boat. The show at that time was completely live. You saw what you got and you got what you saw. I remembered when Sinatra — I was close to Sinatra — and what happened with loading the audience, not with plants.

“Schlatter went and got three busloads of young students, girls, so we could have an audience. It was like a studio audience, but it was on the boat and we planted all the girls in the audience. We had cameras doing reverse shots over his shoulders from the back with the girls screaming and everything. We gave them, I think, five dollars apiece to do it, just for a little present. We said, ‘Scream, the cameras may be on you.’ That was set up.

“When we started to rehearse, he come in unassuming, cute. He come in with his guitar. I introduced them and Harry James said where’s your orchestration? He said I don’t use an orchestration and he picked out one sheet of music, like a lead sheet, no other parts. No saxes, no trumpets — not an orchestra arrangement. He said here it is, and it was one sheet of music for rhythm. I watched and they started to laugh at him. That hip laugh for those days: Oh, look what we’ve got here, a hick, the new kid on the block. He started to strum on the guitar and said all I want is rhythm.

“The band kind of faked whatever song he was doing, and I caught a glance of Buddy Rich and Harry James looking at each other. Buddy Rich made a square sign with his fingers and pointed at Elvis. They looked at each other like, what have we got here? Where the hell did he come from?

“I caught their eye and I walked over and said why did you do that? I had a little beef with James and Buddy Rich. I said I saw you make those signs to one another, that’s very rude of you. I caught you. Wait till you see him. I saw him, and you’re going to be surprised. You’re mocking him. Don’t put him down until you see him. He hadn’t performed yet.

“Then he started to rehearse and he started to wiggle and all that stuff, with his stuff, and sing. The audience was not in, this is at the rehearsal. They looked at him — it was something new, they never saw a kid like this before. He was an original.

“Then the buses showed up and we did the performance. They were naturally, of their own will, screaming because of his looks and he was so adorable. And then he started to wiggle with his butt and all that stuff, you know, his style, and they’re standing up screaming. We had cameras all around. Regardless of being set up, they did it naturally. I didn’t even have to tell ’em. We caught everything on camera and it was live.

“The show went over tremendously. It was one of the first color specials. When the show was over you couldn’t keep the dancers in our cast away from him. They were all after him. He was a sensation that night. He was terrific.

“It was the second show I did with him ‘Hound Dog.’ I was the MC of the Texaco Star Theater Starring Milton Berle. It was strictly a variety show.

“When he got through, I used to work with the performer, whoever it was, we worked together like an after piece, or I was weaved into their act. So when he got through I did some stand-up talk with him. And he was very shy. This was new to him, and I broke him up. He couldn’t keep a straight face. This was a new business, a new alley, for him. I liked him and we got along very well, but when we got to do the live performance, he broke up while I was doing shtick with him. I put my arm around and said This is make-believe. Laugh it up. I said, come on, I laugh when you sing. Berle-isms. But by laughing it up naturally at me, he was more relating to the audience — like a new kid on the block, he was enjoying me. It set a pace for our audience.

“I booked him back right away because he was a big hit. He was fresh and he had a new thing to show an audience. He jived and wiggled and all that stuff, with his foot and everything.

“I received about 300,000 letters from parents — they were not fan letters, they were pan letters — that said, Uncle Miltie, how dare you allow that young boy whose name was Elvis something…”

“After the first appearance on the Hancock, because I was leading the pack on TV. When he appeared with me, he was in the first of four specials. After my audience, and I played to a lot of young people, kids, with my style, I was obvious with visual hokey bits, pie in the face, falls, flops, etc. Today it’s Jim Carrey doing this. I had been doing that for years, I did this ever since I started doing a standup, we used to call it a monolog, that format turned out to be Texaco.

“After the first appearance of Elvis, I was still number-one in the ratings.

“A week later, instead of me receiving thousands and thousands of fan letters about me, written to me, I received about 300,000 letters from parents that said — they were not fan letters, they were pan letters, which was the first time I got them in my career on the air — Uncle Miltie or Mr. Berle, how dare you allow that young boy whose name was Elvis something…

“I got the blame for booking him on the show, because they thought it was just out of line with the gyrations and everything and they never saw anything like that. We’ll never let our children watch your show if you’re going to put a performer like that on gyrating and doing those things. The way he wiggles is really rude and distasteful and all that. They thought that was terrible.

“After having all these letters opened, they were practically all pan letters from my fans who loved me all those years. We’re going around in circles because all that shit is happening again with cable. Censorship in those times was terrible. But this came from my audience.

“I immediately called Parker. Before I told him I received these letters against Elvis and blaming me, I said, Colonel, you’ve got a star on your hands. If they were all of the same taste — how dare you? — when you receive that many don’t’s against the yeses, it means they watched him. Elvis never knew anything about this; it was just between Tom and myself and Abe Lastfogel cause I’m kind of show-wise, because when you receive those kind of letters and they’re all the same and they come that heavy, they’re watching him. He must be hot. And he’s going to be hotter. He was an original, not a copy. He was who he was and he created a new style.

“That’s one of the reasons he was such a sensation. That’s one of the reasons I booked him back. We’re talking about ratings and numbers.

“I was very broad, a wise guy, very flippant, very brash in my style, but that was my style. Critics said I was too wild, too visual, too slapstick. This is before the Three Stooges. I was broad. I did all the broad visual things to please the public. In the ’30s, Walter Winchell wrote something in his column I never forgot: Nobody likes Milton Berle except his mother and the public.

“He was one of the nicest young gentlemen I ever met. He listened because he was new to this side of show biz. He had respect. I never knew him to say anything bad about anybody. I really loved him. As I look back, I don’t feel I’m responsible for his success, I contributed to his success. I felt very close to him. He was always a nice guy and he did his duty with the war.

“I had four specials and I had done two. I had him for the first one and the third one, then the season ended. I was ready to use him again. He wasn’t available for the fourth special. I should have signed him for the four specials. We did the fourth special and that was the end of the season. I was ready to book him on, but we only had this one show and we couldn’t do it.

Were you afraid to book him again after 300,000 letters of complaint?

“Of course I was. I was concerned that maybe I would lose my audience, too, but I didn’t. I didn’t. I just stayed where I was. I was concerned about for myself, but more happy for him. They had never seen him. It was like a discovery. When you receive that many fan letters or pan letters, you know you’ve got something. So I was happy. It did affect me a little, but I got over it. I was too busy working and doing the show and other things and producing and writing and performing. Fortunately, audiences who have favorites forget the scandalous things said about them. If the audience likes you, and they’re with you and your fans are with you, and you’re on top…so many stars overcame adversity of bad notices.

“Did I feel a hurt? Was I afraid it would do something to me? Yes, but just for a few weeks until it got around that I had something to do with discovering him, and the plaudits went the other way. It didn’t worry me. I stayed on. This is my 50th year in television and my 85th year in show business. And I got a birthday coming up in July, I’m going to be 89.

“I wouldn’t tell you all this shit if I didn’t want to be quoted. I want to be truthful with you. I want them something on Presley that’s different, that they don’t know about it, don’t read about. Something that you got a scoop on.

“Alright, baby, let me hear from you. Take good care of yourself.” ◆