In the fall of 1975, an envelope from England arrived at the Trouser Press (I was going to say office, but we didn’t have one yet) mail box at the Grand Central Station Post Office. Inside, typed on nearly translucent paper, were two articles about bands on the London scene. I still have the handwritten letter that accompanied them: “Dear TOTP: Here are two unsolicited manuscripts for you to throw in the dustbin. Like the magazine.” It goes on to correct some details in a Brinsley Schwarz discography we had published and offers a witness statement about that group’s direct predecessor, Kippington Lodge.

One of the articles concerned the windup of Ducks Deluxe, a rocking pub band we were aware of, not just from our assiduous perusing of the British weeklies but because RCA had seen fit to release their first album in the States. The writing was smart and strong, and we were delighted to publish it in our next issue (TOTP 11).

The botched byline, we soon learned, was the result of misreading a handwritten name at the top of the piece, whose author was actually Pete Silverton. (In those amateurish days, we didn’t feel any need to get in touch with an author who’d sent something in on spec — if we liked it, we ran it, and then sent a small pittance of payment. No careful back and forth of editorial collaboration or consultation.)

A year later, we got another piece from Pete, which filled both sides of ten sheets of onionskin. It was about a band we’d never heard of: the 101’ers. The writing made it a great read, but according to the piece, the band had broken up just as he finished the piece, leaving one posthumous single as its legacy. We were cool with obscure and defunct, but 6,000 words on a local London group we’d never heard and likely never would hear made the idea of publishing it a non-starter.

Luckily, I’ve kept that piece in my files all these years. Even more fortuitously, I’ve known Pete the whole time as well — we’ve done birthdays together and hung out whenever one of us was in the other’s town. He’s a brilliant and charming scholar of popular culture, a man whose friendship means quite a lot to me. When I came across it recently, I recognized its historical value. Don’t miss the surprise ending.

With Pete’s permission, nearly a half-century after it was written, this is its first appearance anywhere. (The British spellings have not been altered, but I can’t abide punctuation outside close quotes, so I “fixed” those.)

The 101’ers – 1976

By Pete Silverton

The 27 bus cuts a vicious social swath across London, from the urban blight of Archway to the epitome of suburban chic, Richmond. Around half-way, after the seedy bookies’n’boozers of the Edgeware Road, but before the mandied sewer of Notting Hill Gate, if you look out of the window, you’ll see, hastily sprayed on a corrugated iron fence, “Letsagetabitarockin.” You may well not realise it, but you have just borne witness to the spoor of a mean and nasty rock’n’roll animal.

Friday, 23rd April, the Nashville, West Kensington

A pub gig that’s fast becoming the middle-rank London venue. Dingwall’s may have the edge in drunken rock’n’roll stars propping up the bar, but at the Nashville the beer’s cheaper and better and, apart from the Kensington “oh you must go there darling” trendies, the audience are there because it’s Friday night and they’re damn sure they’re gonna get drunk and have FUN.

All of which means the energy level is pretty high when the ghastly red curtain parts to reveal the 101’ers tearing, hot beat band style, through Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business.” The classic four-piece band. Snakehips attempting semi-legal homicide on his Japanese drum kit. Dan plonking out some four-square solid foundation lines on his very beat-up bass. And to give it the right amount of depth, Evil Timperlee, resplendent in “you lookin’ at me, mate?” shades and bargain basement Hawaiian shirt, picks out a sweet lead on his factory fresh looking modified Gibson SG Junior.

But the main reason for seeing the 101’ers is the short stocky guy with cropped dark hair intent on further mutilating his already near-to-death Telecaster — Joe Strummer. He’s already been acclaimed (in print) as one of the few true rhythm guitarists. But he’s much more.

Not for many a year has there been such a dynamic new stage performer. He swoops, dives, stumbles, duckwalks and bumps all over the stage — and always makes it back to the mike in time for the next line. Maniacally thrusting the beat ever forward. Forcing from his larynx Berry’s apocalyptic diatribe against oppression, he nigh on convinces you that “Monkey Business” was written for London 76 not Chicago 56. If you thought Wilko’s head was going to fall off, wait till you see this boy. Once or twice, I’ve been certain he was going to rock’n’roll himself into an epileptic seizure. A veritable embodiment of the orgasmic ecstasy of pain.

The comparison with the Feelgoods is inevitable, if only as a point of reference, but rather misleading. Joe’s neither as accomplished a guitarist as Wilko, nor as polished a singer as Lee Brilleaux. But, on a good night, he can surpass both of them rolled into one. And he writes better songs.

See him on the street or drinking at the bar, you won’t look twice. When he picks up his guitar, puts on his pink suit and plugs into his Vox AC30 he’s transformed, and proceeds to enact every rock’n’roll fantasy you ever had and a few new ones you’ve never even thought of. His closeness to the street makes those fantasies direct and catholic wide-screen translations of every move you made this in front of a mirror at sixteen.

Another common comparison is the youthful Gene Vincent. It’s an element for sure but rather like saying Jagger did nothing except rip off James Brown. When he’s working at the peak of his abilities, Joe Strummer runs the whole gamut of rock’n’roll star movin’ actions, from Presley’s knee-twitch through Berry’s dips and slides to Dylan’s arrogant immobility. This collage is itself remarkable for its freshness, but, not content with being a mere impersonator, Joe adds a constant quivering intensity that often makes you worried about his body’s ability to remain in one piece.

“Monkey Business” disposed of like a sweat-sodden wristband, with barely time for the title, they’re full-flight into “Hipshake.” They claim never to have heard the Stones’ version (which I don’t believe), but their treatment does sound rather like Slim Harpo himself about to suffer cardiac arrest from too many amyls.

Again, barely a break for introducing the next song and we’re back to where we came in, “Letsagetabitarockin’.” Although not Joe Strummer’s best song, it’s a powerful anthem and more than worthy of immortalisation on that stretch of corrugated iron.

The 101’ers are the first band to break out of London’s latest addition to the sub-genres of rock’n’roll — squat rock. London’s housing shortage has yet to recover from the bombing of World War Two. It’s particularly acute among young single people who are uncatered for by the public housing authorities. One solution is to move into unoccupied houses, generally those scheduled for demolition. The name of that game is squatting. The amenities are often primitive and the security of tenure far from cast iron, but there’s no rent to pay and, in areas with a large proportion of squatted housing, there is sometimes a sense of community commonly missing from city life.

About a mile and a half northeast of Portobello Road is (or rather was — it’s been razed to the ground) Elgin Avenue. The site of a famous squat, where the inhabitants fought for, and won, rehousing in council property. One of the focal points of the community was the Chippenham pub. The origins of the 101’ers were on its first floor, in one of those rooms of dingy lighting, dusty carpets and framed pictures of the Queen that pubs will let out to anyone who comes up with the requisite readies.

Joe Strummer: “Reason I started it, see, was because I had nothing to do in the summer. I was living rent-free, but I needed a few quid. So I thought of throwing together a quick group and going to play for the Irish.”

Instead, late in 1974, he and a few friends came up with the one pound rent for the room at the Chippenham and formed the Charlie Pigdog Club. They turned up the first week to discover that they had obviously tapped some need in the local populace — the joint was jammed. Bravely and deeply embarrassed, they carried on with their plan to jam a little (through the record player amp!) As they freely admit, it was “dead rough.”

Having committed themselves to a ready-made audience, they practised hard during the next week and the Charlie Pigdog Club became a regular Wednesday night fixture. They were building up a hard core of fans when the club had to be closed in the face of overwhelming violence. Apparently, one night, internecine warfare erupted between the gypsies and the Irish, with support from some mad dogs. The band played on regardless, and the bloody carnage [was] only called to a halt by the entrance of the officers of the law.

Shortly after, the landlord brought the builders in, or so he claimed, and the Charlie Pigdog Club and the first incarnation of the 101’ers met their ends.

Up to this time, the 101’ers, like the other bands that played the Club (Timon Dogg, Here and Now and The One Band), had only been a scratch pickup outfit. Around the basic rock’n’roll three guitar and drums centre, various horn players and vocalists had come and gone. Now, with nowhere regular to play, the group were driven to be more professional, shedding excess members until they had slimmed down to their ideal of being a “four-piece, like the Beatles.”

Despite the loss of the uncommitted supernumeraries, the band was still hardly bulging with musical experience. Snakehips had taken up drumming because the previous drummer had gone away for the summer (‘74) and the communally owned kit was lying around the house unused. Perhaps because of this crash course entry into playing, his fresh directness quickly became an essential ingredient of the band’s straight-ahead simplicity. Mole, the original bassist, had picked it up because, like Everest, it was there. Only Joe and the lead guitarist, Evil Timperlee, had any rock’n’roll history. Even then, Joe’s was not deep: the best-known section being with the allegedly legendary Cardiff-based Johnny and the Vultures. Evil’s was by far the richest and widest background. Since playing in a band with Fairport Convention’s first drummer, Martin Lamble (who was killed in a car crash in 1969 at the underdeveloped age of 16), while still at school, he’d consistently scraped a living as a musician. Eventually the attraction of unsuccessful acoustic (not folk, he’ll remind you) bands palled and, in January 1975, he was drawn to the beat combo approach of the 101’ers. He joined at a critical juncture. The band was eight strong at that point, and his unassuming but tastefully layered guitar work was a singularly powerful factor in enabling the four-piece line-up to be a viable proposition.

They quickly got successive and very successful residencies at the Elgin and the Windsor Castle. Moving on, there being no alternative, they plunged neck deep into the round of London’s pubs, clubs and small colleges. It may sound like a ride ‘round the park on touring push-bike in the company of friends. In reality, it’s more like pushing a Kawasaki 900 up a 1 in 9 gradient. Joe said of one venue, “At the time, I thought it was the cat’s knackers (a favourite phrase of his). Now I wouldn’t go back there if they laid on a bloody Rolls Royce.” But, despite often being greeted by nothing more than drunken stolidity, their hard work did widen their coterie of fans.

Friday, 9th April, the Hope and Anchor, Islington

This is aImost home turf — the scene of one of their most publicised successes so far. Fred, the landlord, held a tight “Pub Rock Proms 75” in the claustrophobically atmospheric cellar. The 101’ers opened it. Chas de Whalley enthused in the NME: “The 101’ers are what rock is all about. Enthusiasm and zest, very fast living with a hint of violence is and, above all, simplicity.” He dubbed their style “Squat Rock and the Heavy Gauge String Sound.” That was November last year. They’re a little more sophisticated now, but on this damp Friday in April, they rock up a comparable, if not even more turbulent, storm.

It was such a good gig that I remember precious little of the details. I remember Joe introducing “Promised Land”: “This is a Chuck Berry song. He did a terrible version of it. Elvis did it even worse. This is dedicated to the man who did it best: Johnnie Allen.” The 101’ers drive on Berry’s gentle questioning of the solidity of the American Dream brings it in close second to Allen’s own odd hypnotic Cajun treatment. I remember their energy-drenched “I Saw Her Standing There.” I remember they did “Rabies,” their own, announcing it cryptically as a “government song.” I remember the only low point being “Surf City” — a fine slow number of their own, but its true merits remain obstinately hidden in live performance. The only other thing I remember is that it was the first time I realised that Joe Strummer was “Star Material.”

I’d put my reputation on the line that night. I’d called up every deviant I was still on speaking terms with and told – ņay, begged — them to hotfoot it down to the Grope’n’Wanker that night. I was vindicated. Joe mesmerised the lot of them, turning on a truly rapacious performance. From the time he plugged in, he didn’t let up proving his ability to torture his throat, his guitar and the audience’s limit of enjoyment. If his mum hadn’t assured me he was a thoroughly nice boy, I’d have sworn he’d learnt his three chords from the notorious Marshall Beria, onetime head of the GPU. He moved around the minuscule stage so much and to such purpose that the only possible comparison is Jagger. If that seems exalted company, so be it.

Harbouring in the warmth of their close-knit group of friends and fans, the 101’ers eked a living around town and showed their style and street commitment by playing innumerable benefits. Their hard work began to be repaid in the form of dividends like Chas de Whalley’s review. Their covers, their own songs and their crudely powerful musical empathy all began to shape up into consistent sets of quintessential rock’n’roll.

Then, in January this year, because of the normal “musical differences,” the bassist “left.” This could have been a tragedy — too many musicians have visions of being a virtuoso. Mole could never have been that; but he knew which end of the instrument was which, kept it simple and didn’t think he was Jack Bruce, What could have been a tragedy was triumph. Despite having been a pro for six years, done lots of sessions and been classically trained to the point of being offered a place at the Royal College of Music, Dan Kelleher was a real find. As well as putting the final polish on the arrangements (which he’d been doing before he joined) and laying down a solid underpinning, he looks the part of a beat group bassist. With his medium-length black hair, shy smile and insistent politeness, he could have been born in the Cavern.

Wednesday, 14th April, Rebecca’s, Birmingham

The city that puts flesh on that vogue word of sociologists — anomie. I’ve never been to LA, but this is close enough, thanks. They’re both supplicants to the motor car. But Birmingham is poorer — some of its inhabitants have to walk. Mostly given over to freeways, the city centre of low-level, high-level and subterranean walkways resembles nothing more than the world ten minutes after everybody [has] left. Even if you manage to avoid the muggers in the subways, it’s inadvisable to stand still — a drunk might mistake you for a pillar and accordingly piss on you.

Realising that the life of an up’n’comin’ band was not all the intimacy and enthusiastic crowds of gigs two miles from their house, I’d come up with them in the van to see how to they fared on unknown territory (they’d never played Birmingham before) and experience a little of the life of a band on the road.

Joe only becomes fully animated when he’s listening to or playing rock’n’roll. He sat in the van scowling at a copy of Melody Maker. “Gloria” comes up on the cassette. Instantly his ear is fixed to the speaker. Everybody likes rock’n’roll, but the intensity of his reaction is almost frightening.

As always, they’d been late setting out. In addition to the “getting it on the road” problems of any band, there’s Joe’s greyish pink stage suit. As much as it’s a visual symbol on stage, it’s a never-ending source of delays in the organization. It gets lost. The cleaners closes. Or Joe forgets it. This time the cleaning ticket went missing for a couple of hours.

Joe’s always disappearing, physically or mentally. He’s always human, but he only becomes fully animated and enters society when he’s listening to or playing rock’n’roll. Withdrawn, he sat scrunched in the corner of the van scowling at a copy of the Melody Maker. “Gloria” comes up on the cassette. Instantly his ear is fixed to the speaker until someone finds him the phones. Everybody likes rock’n’roll, but the intensity of his reaction is almost frightening. Then again, it is their usual closing number.

On entering the club, the roadies were regaled with shouts from the staff, “Close the door. It’s cold.” (How else do you hump in the equipment?) A first taste of Birmingham’s world-renowned hospitality. Looking ‘round the club, Joe Strummer noticed that they’d got the name wrong. He pointed it out. With unshakeable Brummagen stolidity, the woman behind the counter enquired, “Does it really matter?” Every insistence that “Yes, it does” and all allusions to Mark Twain’s lack of success as Mr. Clemens failed to divert her from her grubby knitting.

After being told by Boogie, the roadie, that the soundcheck would be the best ten minutes of the night, I ventured out to be delighted by a speed-crazed “Promised Land.” A couple of false intros and they were into their own “Two Silent Telephones” and trying out a new method of checking the sound. I don’t know how the new method worked out, but “Telephone” became progressively more ragged until Joe left the stage in disgust — there were people in the club already and slipshod jamming would ruin their image.

It was the best part of the evening. Birmingham ain’t no place for rock’n’roll. I really don’t know how it’s produced Stevie Winwood and the Move. Despite the free tickets that had been given away, the club was rather empty. And what action there was, was going down in the disco. I don’t know what it was like. I didn’t get past the door. The smell turned my stomach. I was told it was the food. Which made sense when I noticed the unhealthy faces in the audience.

If all else fails, Joe would win the rock’n’roll spitting crown. The gobs helter-skelter from his mouth, Concorde in speed, jumbo in size…the only person I’ve ever seen squeeze out the foam mike cover halfway through the set.

The mistake over the name came back like a bad case of syphilis. The very smooth “progressive” dee-jay: “Let’s all give a big Birmingham welcome to 101 and the others.” On being informed of his error by the band, he only managed to correct it to “101 and some others.” Resignedly, they let out the clutch and powered into “Roll Over Beethoven.” The set was a good solid creditable professional performance. They played hard and well but with such a meager audience, it could never really take fire.

The thing I noticed most was that, if all else fails, Joe would win the rock’n’roll spitting crown. No trouble. The gobs helter-skelter from his mouth, Concorde in speed, jumbo in size. Arcing to the mike, they spray all over the monitor. He’s the only person I’ve ever seen squeeze out the foam mike cover halfway through the set. Honest. It’s just as well he doesn’t play harp. The front two rows’d drown.

Backstage. The only members of the audience who’d seemed to enjoy the band were packed into the tiny sordid dressing room. They were from the local hip record store. They joined the band in insulting the city and its mothers. A friendly piece of human contact that gave the band the strength for the drive back.

Having dipped my little finger into the life of rock’n’roll on the road, I was glad I’m only a listener not a player. They’re welcome to their motorways, greasy food and unpleasant club owners. Which is a measure of their strength. They hate it, too, but they still get up there and do it.

Back at the Nashville, they’re celebrating another of their heroes, beating out Bo Diddley’s “Don’t Let It Go,” eight to the bar. This segues powerfully into the self-penned “Motor Boys Motor.” Although the set is going down very well, it’s becoming clear that the few drinks Joe had before going on are slowing him down. He’s still moving but he’s no longer the same overwrought bitch on heat.

Which may not be a bad thing. His riveting presence can easily divert your attention from the manifolds virtues of the music. Their personalities are as incongruous as those of any band, but onstage, they sink their differences and work together . . . closely. Everyone who’s seen them a lot has been astounded by how much they’ve improved lately. Gone are the days when their crudity and simplicity were of necessity; Joe’s given up smoking and his vocals are already, without a gram of punch being lost, becoming more measured, more confident. Snakes is beginning to embellish the basic rhythm, throwing himself around the kit a little more without sacrificing any of the directness. Although he’s yet another otherwise sensible grown man who inexplicably lusts after Joni Mitchell, Evil is rapidly losing the undertones of low-key acoustic “tasteful” playing which used to dog his guitar work. While he has none of Mick Taylor’s soulfulness, he is now able to varnish Joe’s three-chord limitations with some of the biting attack which Taylor used to overlay Keith’s lurching rhythm. And, in four short months, Dan has laid indisputable claim to his place. His confidence on the bass is gaining rapidly (his previous experience was mostly on piano), providing that essential sweeping fill at the bottom end.

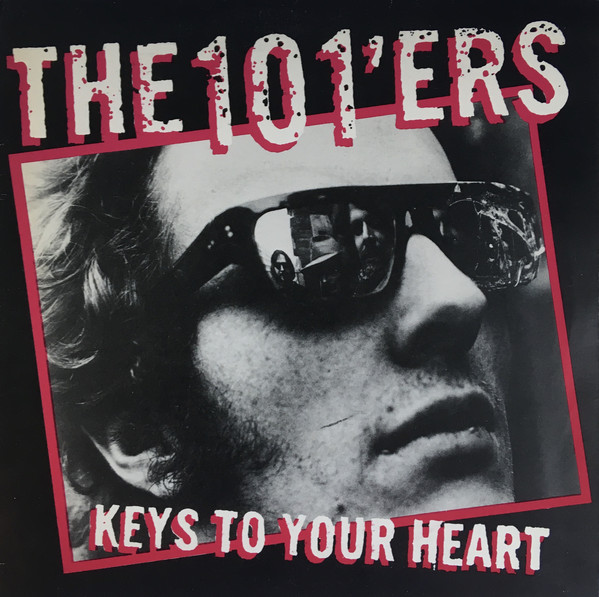

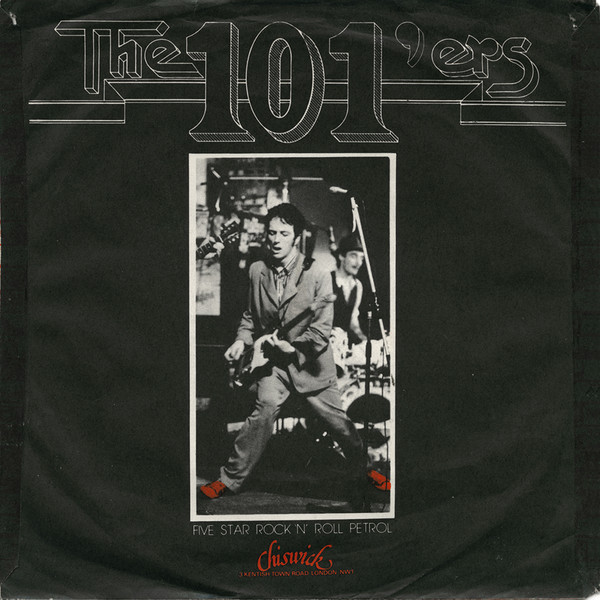

The clue to this quantum leap in quality is the next number, Joe Strummer’s shot for the top, “Keys to Your Heart.” The exigencies of tight budgets and three-hour recording schedules forced them to listen to their playbacks and shape up but quick. This harsh but immensely helpful mirror was provided by Ted Carroll. As well as being London’s leading oldies shop entrepreneur, he’s got his own little label, Chiswick. “Keys,” backed by another original, “Five Star Rock’n’Roll Petrol,” should be its third release. I’ve heard a rough mix and, unfortunately, although the song’s true virtues are hinted at, its power is cruelly watered down by a packing case drum and thin guitar piece of production. If Ted Carroll really wishes it were 1966, why doesn’t he go over to the States and dig up: the Shadows of Knight. But it’ll probably be a collector’s item in years to come and, because it’s on a tiny label, the 101’ers should get a chance to re-record it with the majesty and guts it deserves.

The reception it gets at the Nashville is more than warm. Which is good because the punters can’t all have seen the 101’ers as often as I have. That they’re on their way up is clear tonight. In this set of mostly originals, their own songs are going down as well, if not better than, the standards that everybody knows. That’s encouraging for the band — and crucial with a single on the way.

Sunday, 18th April, the Roundhouse, Chalk Farm

The world’s most famous railway turntable. The bill is crazy. Van der Graaf Generator topping with the newly reformed Spiders From Mars in second position. The 101’ers were opening act –what do you mean? You want money as well? This is a prestige gig!

The less said about VdGG, the better. The Spiders, as someone remarked, looked as though they’d been taken out of crates marked 1971. Six-inch platforms. Shag-cut, shoulder-length dyed hair. Gaudy sequined threads. If the band looked as if glitter-rock still ruled, the singer did a fair to middling, impersonation of a down market Tom Jones. I lost all interest after one and a half numbers and concentrated on their fans, who were much more interesting. Obviously long-term Bowie aficionados, these 17-to-19-year-olds, mostly male, all looked like my cousin, sporting the 1971 Ziggy style as diluted for authoritarian parents and culture-shocked headmasters. Don’t get me wrong. I think Bowie’s fab and all that, I just don’t think much of his fans. They only seem to see the surface flash of the man and his, music, not the why and wherefore behind it.

But, like it or not, it’s kids like these that the 101’ers have got to reach, if they want to move up rock’n’roll’s shaky ladder. They didn’t this night. Blank stares, immobile feet and arses- firmly parked on the grimy floor was their only reward. Except for a fraction of a second. Halfway through the 101’ers’ set, the Spider kinder spotted one of their heroes at the side of the stage. They all jumped up and waved at the object of their affection. Luckily, because of the lights, none of the 101’ers saw this. If they had, they probably would’ve packed up and gone home there and then.

These kids were one of the problems besetting the 101’ers that night — their monopolising the area directly in front of the stage nixed any feedback that was coming from the audience. The other problem was the acoustics. The domed roof is fine for the quiet applause that plays and “progressive” bands draw, but as it sucks in 90% of the audience response, it’s a dead loss for kick-ass rock’n’roll. The crowd have to go absolutely bananas before it sounds like there’s more than two of them. And a true rock’n’roll band like the 101’ers only really turn it on when the punters are throwing back cartloads of enjoyment.

Nevertheless, their show did have its high points. First off, “Junco Partner.” Lasciviously introduced as “a song about drug addicts,” James Wayne’s dispassionate New Orleans shuffling is transformed into a frantic quivering show-stopper. Joe stands stock still, snarling out the words.

“Down the road, down the road

Six months ain’t no sentence.

One year ain’t no time.

They got boys there in Angola

Doing nine to ninety-nine.”

He manages to convey some of the desperation of addiction while indulging in none of the histrionic theatrics that Lou Reed now uses on “Heroin.” And it’s a bitch of a rocker.

The other not-to-be-missed section was the last number, as nearly always, “Gloria.” Every frontman needs someone to bounce off, and Joe uses Snakes, the drummer. It makes sense, because the jangling rhythm is inseparably tied to the ride of the cymbals. One of Joe’s favourite moves is lying down backwards over the bass drum while Snakes tries to avoid smashing open his skull. This symbiosis is crucial on “Gloria.” On the original, when Van gets to the lucky lady’s door, the regular tap of a drum emerges from his Freudian subconscious. At that point, Joe opens the song out, delving, I can only assume, into the same murky territory that Jim Morrison explored on “The End.” I can only assume because I’ve never grasped more than tantalising words and fractured phrases from his Joycean outpourings. I asked [Joe] if he really said anything meaningful. He said, “Oh yeah. Lots. But nobody can understand me.” Heavy intellectual stuff, huh? “No. It’s just me diction. I garble it all out.” Never descending into crude punk monotony, the rhythmic interplay, savage guitar work (feedback ‘n all) and Joe’s plum crazy vocalising, their “Gloria” puts Patti Smith’s back in school where it belongs. And the key to its strength is the stinging rhythmic crunch emanating from Joe and Snakes.

That night, however, their relationship went, shall we say, a little over the top. Thinking or knowing Snakes had made a mistake, Joe kicked a cymbal at him.” Understandably peeved, Snakes was lunging over the drums and going for Joe’s throat before thinking twice and better. Luckily, it was the last bar of the tune. The audience thought it was part of the act and roared almost appreciatively.

It was a two-night show. The same line-up the following day. Apparently, or so I’m told, the 101’ers went down better on the Monday. The place wasn’t very full. Obviously, the same less VdGG and Spiders fans, the better it is for rock’n’roll.

Supporting them at the Nashville were London’s latest are succes de scandale, the Sex Pistols, fresh from a two-page spread in Sounds and an unceremonious ejection from their residency at a Soho strip club. They’re interesting, if only as a comparison. They’re strong in the 101’ers weakest suit – image. Johnny Rotten, the singer, it has been said, looks like a refugee from Belsen who hasn’t had time to change his clothes. He’s backed by three pictures of lumbering Shepherd’s Bush health. The music is rather like the Rolling Stones played by the Reedless Velvets. Their manager owns “Sex,” Lisa Robinson’s favourite shop (or so she says). It sells rubber skirts, cock rings, sensual T-shirts and all sorts of stuff like that. You get the picture. Drawing on the gutter heritage of Iggy, the Sex Pistols lack his genuine outrageousness and fall into the trap of all poseurs — they don’t deliver. They’re like everything you’ve ever been craving to try, done once and foresworn ever after.

The 101’ers shut ’em down. After a sweet as seventeen “I Saw Her Standing There,” they finished with a long version of their own “Steam Gauge 99,” instead of the usual “Gloria.” Joe’s energy pack had recharged and he really went wild, flashing blistering riffs all over the stage, standing on the amps Detroit-style, gunning the audience and severely straining his vocal cords. The rest of the band really stung on the choruses and super-short solos, Snakes particularly. Spraying sweat all over, tip of his tongue tweaking between his lips, eyelids batting furiously to the beat. Top that with a bush hat and a torn collarless shirt and you have a rock’n’roll drummer that Keith Richards wouldn’t let within 100 miles of his daughter. They came back and did a shortened “Gloria” — the applause was loud enough to have merited a second encore but by that time the house lights had already been turned up.

Successful as it was, the gig pinpointed the biggest brake on the 101’ers’ career. Money. The management of the Nashville have hardly thrown their money around — it looks pretty much the same as it did when it specialised in country music. The lights are like those in your Auntie Masie’s parlour. Bright, yellowy and undefined. The very high proscenium arch only makes it worse. All the onus of presentation is put on the band.

Which costs money. Some powerful ultra-white spotlights with maybe some colour fill were needed. The 101’ers sound system isn’t quite up to scratch, either. The twin Vox AC30s for the guitars are super. (A note to social historians: one of the AC30s has YARDBIRDS stenciled inside.) They make a sound like the noises emanating from a two-year old let loose’n’havin’ fun trimming its nails with a blowtorch and gargling on paint stripper, Mean as the amps are, the PA needs beefing up the drum needs some quality specialised mikes and Dan’s bass guitar should be thrown away. They can scrape it together slowly or they can sell their soul to a record company. The Hobson’s choice of rock’n’roll.

Maybe. Just maybe, if they continue to blitz audiences like the Nashville and the Hope and Anchor, they’ll break out. Which is unlikely because, by and large, the punters need to have what’s good in life rammed down their throats. The Stones themselves were stuck in a tuppenny ha’penny Richmond pub until their very own superhustler came along. Andrew Oldham decided he wanted a piece of the action and created the whole mean and dirty image. That’s not quite what the 101’ers need but, if they don’t get some sort of image and the necessary financial backing, it’s possible they’ll remain on England’s chitlin circuit. Which will give me and a few others great nights out, but it won’t be a tenth of what a band of such dynamic potential deserve.

Pertinently tangential footnote

Good as I always thought they were, I didn’t realise quite how electricity-charged the 101’ers were until a week after the Hope and Anchor gig. They transformed the basement’s claustrophobia into intimacy. Carol Grimes and the London Boogie Band, the following Friday, saturated it with oppressiveness. The smoke stung your eyes. The beer was totally unpalatable. They were boring. Carol’s still got a great voice. Any one of the Boogie Band could probably play all of the 101’ers off-stage with one arm in a sling. They’re all from such respected “roots” as the Grease Band and Kokomo, but their enthusiasm for rock’n’roll seems about the same as mine was for school. They shortchanged the crowd by coming on late. Onstage, they were so laid back, as the phrase goes, that I thought they were gonna fall over. And none of ’em could play rhythm guitar. It left such a bad taste in my mouth that I had to rush home and play Exile on Main St. VERY LOUD to reaffirm my belief in rock’n’roll.

My personal pet theory is that you can often tell the quality of a band by the cheer section it acquires. This time I was right. The 101’ers’ lot are young, enthusiastic, democratic and they dance. The Boogie Band’s looked like boutique managers, smiled inanely a lot and obviously considered lighting the cigarette of one of the zombies on stage the highpoint of their social life — they approached it like a parish priest kissing the Pope’s ring. With friends like that, you’ve just gotta be on the slope to oblivion (which Carol doesn’t deserve — she should junk ’em). With friends like the 101’ers have got, you’re in at the bottom end of the career of one of the hottest little combos treading the boards.

Coda

The day, the very day I finished this article, I went to see the band to check out a few factual details. Joe, standing almost suspiciously on the street corner, told me the news, “We kicked out Evil. Martin Stone, y’know him, he’s coming round to check in.” Brushing aside my objections that the last gig I’d seen them play had been as sweet as a kosher pickle (crowd stomping, screaming, calling out the letters of “Gloria,” unaided, unprompted) and that Evil had really started to live up to his name musically. Joe defined the limits of his generosity: “Yeah, but he shoulda always been that good.”

Plan was now for the ex-Chilli Willi honeydripper axeman to dep for a couple of outstanding gigs (I didn’t see either of them but I was informed that they were no more than alright, the highlight being a rendition of “Out of Time” dedicated to all the hippies in the audience), then the band would be totally revamped, Dan switching to guitar, new bassist, younger image, more professional stage show. Of course, it didn’t work. The first serious rupture in the unit had forced those left to face the problem they’d been studiously avoiding. Y’know, the classic trite big one: “Where’re we going?”

The strain was too much. The revamped band never came about, Joe decided to go the whole hog and form a new band with five snotty West London youngsters. They should go far — I’ve only seen them practice but the new guitarist’s songs which look insipid adolescent jive on paper become real punchy’n’dynamic when fleshed out with three guitar spitting Molotov cocktail fire.

The rest of the band? Last I heard Dan was in Stonehenge, Snakes off to teach English to Italians. The single? It still came out (Chiswick S-3) and, with true irony, it’s doing better than anybody could have expected. It’d do even better if they flipped it. Petty record company egotism dictated the murky take of “Keys” that they produced took precedent over the spontaneous crispness of the band’s own production of “Five Star.” “Keys” is the better song. Its sardonic humour still forces its way through — as I’m writing it’s had unanimously warm to very good reviews and is number-one with a bullet in a respected DJs /writers personal picks chart. But it’s the other side that never leaves my turntable. Partly for the memories but mostly because it’s the best no fuss wasted rock’n’roll vinyl I’ve heard since…well for a long time.

If Joe’s new band, Clash, come up with anything as good (and I think they will because the talent is there and they’ve got strong, pushy management), they’ll get rich and famous and I won’t get to see them much because they’ll be busy smashing up hotel rooms, the 101’ers merely a cult memory, if a warmly cherished one.

You win some. You lose some.