The Go-Go’s’ documentary, which is surprisingly titled The Go-Go’s, began streaming on Showtime Friday. It tells the band’s story, giving all the principals ample time to share their memories, acknowledge their flaws, laugh about past excesses and admit regret over one bad career decision: pushing aside their true-believer original manager in favor of the freezing hell of corporate ogre Irving Azoff.

Giving everyone a chance to speak frankly in extensive new interviews, the film covers all the basics. It’s a good, uplifting story of hard work, a dream and dedication paying off in massive (albeit brief) success. No one dies and, despite enough discord and resentment to collapse the band after three LPs, at the end of the film the five of them are back together onstage making music and appear to be enjoying themselves. The women, all now in their 60s, are still in good humor with positive attitudes — no one is AWOL or fucked-up or embittered.

It’s hardly an action-packed tale, although it still provoked feces-flingers to come up with such inevitably exaggerated headlines as the NY Post‘s “Inside the Go-Go’s vicious, drug-fueled ride to fame.” Yes, they imbibed in drink and drugs, goofed around, had sex and chucked out two original members (making their manager do the dirty work, natch.) But as musical stories of rise, fall and redemption go, this one is — thankfully for the people involved — relatively tame. While acknowledging pressure, anxiety and collapse, it all seems rather wholesome for rock and roll. In the film’s funniest segment, a set of Polaroids shows them each in bed, pretending to give birth.

Romance, other than an early affair Jane Wiedlin had with drummer Gina Schock and her subsequent flirtation with Terry Hall of the Specials that produced “Our Lips Are Sealed” (his words, her music), is never mentioned; solo careers are downplayed nearly to the point of omission. I would have enjoyed an appearance by Australian country superstar Keith Urban, explaining how he got paired up with Jane and Charlotte Caffey to write a hit single in 2000. And given that they worked on it for years, promoted the shit out of it and saw it run on Broadway for more than 200 performances, the band’s Broadway musical, Head Over Heels, could have gotten more than ten seconds of screen time.

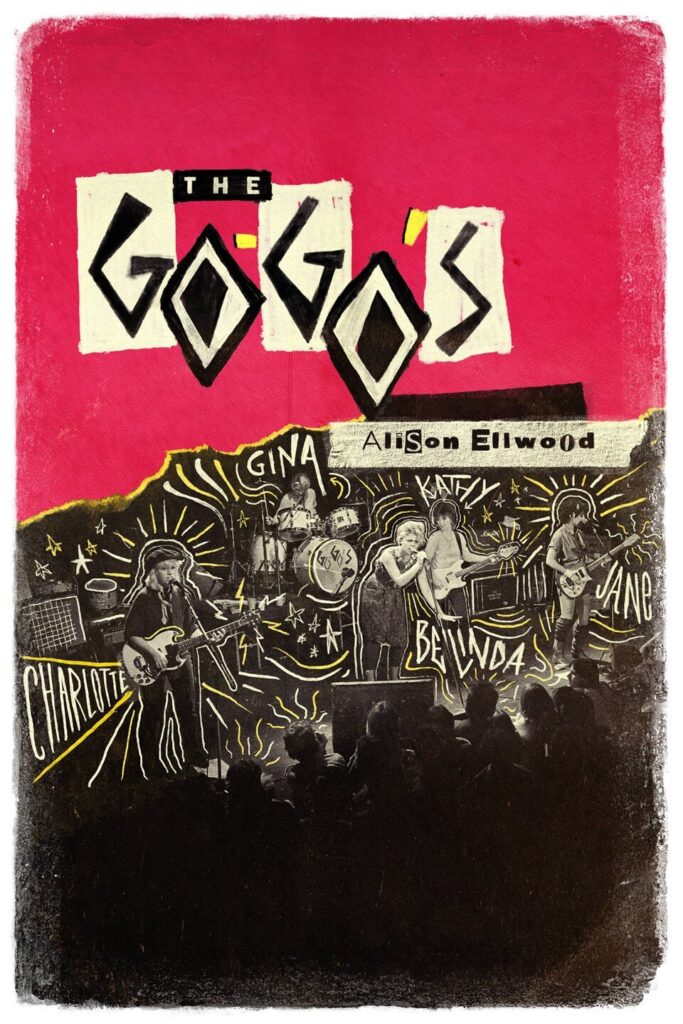

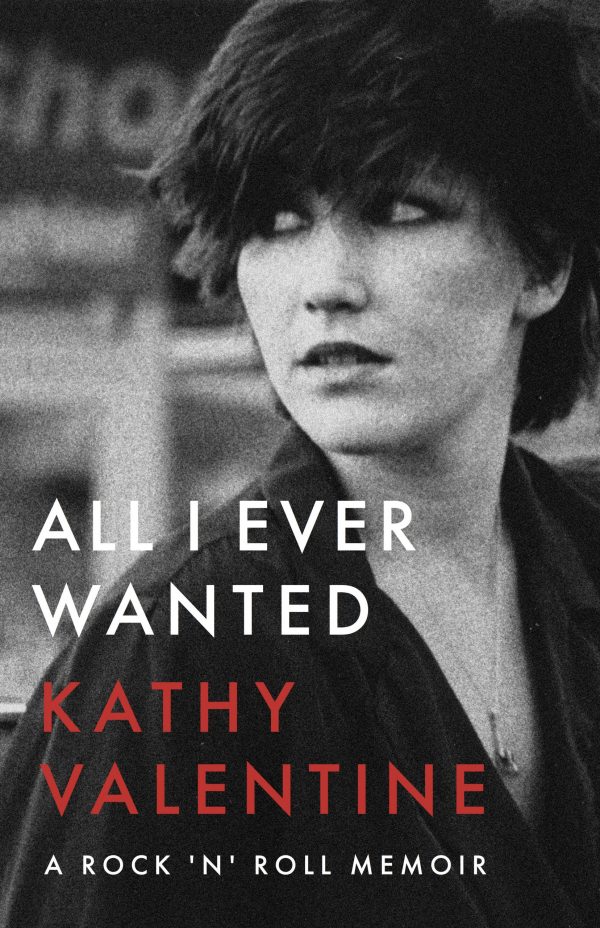

Anyone who knows about the band or has read the books by Kathy Valentine (compelling, self-aware and, at times, coruscating ) or Belinda Carlisle (not so deep, but the first half of it could have been a road map for the film) will find nothing shocking onscreen here. On the fun facts ledger, I learned that Wiedlin’s 1984 resignation was over a music publishing dispute and that Valentine wrote “Vacation” and recorded it with the Textones before joining the Go-Go’s.

Caffey’s addiction to heroin was a shocker when it was first revealed years ago; she makes no effort to downplay it here, but it’s still hard to grasp how the oldest, least punky member of the quintet would be its worst risk-taker. She talks about getting sober (partly crediting Paula Jean Brown, the bassist who joined the lineup after Jane left and gave Belinda the song that jump-started her solo career), and it’s heartwarming to see her looking so well in her interview. (It is, however, jarring to see how much older she looks in the most recent footage. I don’t know how much time elapsed between the two.)

And while the film rightly celebrates (more than once) the Go-Go’s’ proud glass ceiling achievement — they were the first self-contained all-women rock band to have a number-one album — there is no mention of the Bangles (who followed them, albeit with more outside songwriting) or Girlschool (who preceded them and never had comparable success). The Runaways are acknowledged, but without comparison or discussion.

I don’t mean to sound disappointed in, or negative about, the film, which does full and fair justice to both the band and those left behind in its wake (including founding bassist Margot Olaverra). It neither glosses over nor overly glorifies anything bad or good that may occurred along the way. It’s efficient, fair, well-researched and smoothly edited. I’m sure some observers will make inflated claims for it because it documents important progress for women. But just as the Go-Go’s rewrote rock history without breaking any stylistic eggs, the film stays well within the bounds of bio-piccery. Which, in the case of a swell band that had its short, shining time and then largely faded from view, is good enough.

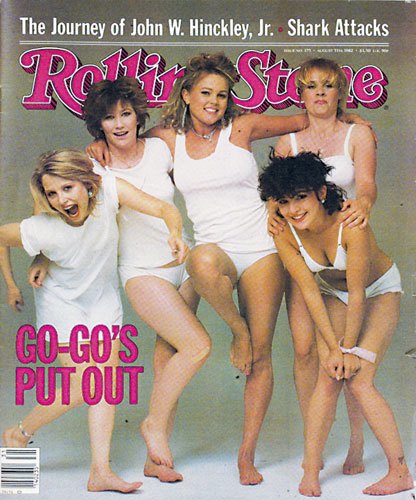

Journalist Steve Pond, who does not appear in the film, recently wrote in The Wrap about the icky cover line and the circumstances that led to Annie Leibovitz posing the band in modest white underwear for his Rolling Stone story. (In her book, Belinda recalls they recoiled at the idea — in her case due to past body issues — but, “Once we got in the underwear and saw the first Polaroid test shots, we understood what she was going for and we enjoyed ourselves. The result — well, it spoke for itself.” I don’t know how to take that last remark, but then she posed for the cover of Playboy in 2001.)

As it wraps up, the film’s ultimate purpose is finally revealed. At one point, Ginger Canzoneri, the soft-spoken manager who got her heart broken by the band she fought for and loved so dearly, recalls Rolling Stone supremo Jann Wenner hanging up on her when she called to convey the band’s unhappiness at being objectified. And she wonders if that’s why they’re not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Stewart Copeland and Chris Connelly — remember him from MTV? — add their incredulity at the omission, and there you have it: The Go-Go’s is a 95-minute highlights reel to embarrass the nominating committee into rectifying its 14-year oversight. I hope it works.