“What I’ve been trying to do has never changed in terms of the spirit that made me create Devo in the first place and made me be an apostle of de-evolution.”

Jerry CASALE

By Dave Schulps

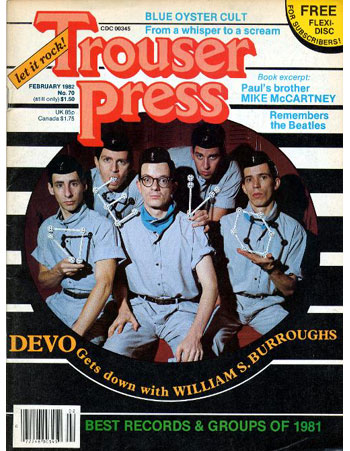

A peek into the Trouser Press archives confirms that, on the two occasions when the band graced the mag’s cover, we went BIG with it. The first one, issue 35, bore the cover line, DEVO: Future of Rock or Total Crock? and featured perspectives on these divisive up-and-comers from three different writers: DEVO Yes…DEVO No…and DEVO Maybe. The second, 35 issues later, was a bizarre conversation between DEVO and William S. Burroughs that was unlike anything else we ever ran.

So here we are, not another 35 issues, but 41 years, later. Following the deaths of original drummer Alan Myers and keyboardist-guitarist Bob Casale within eight months of each other in 2013/14, Devo has devolved from an active band into (a) Jerry Casale, a.k.a. DEVO’s Gerald V. Casale, who would like to continue Devo’s musical legacy, and (b) the Mothersbaugh brothers, Mark and Bob, who appear happy to let it be and concentrate on composing for visual media via their Mutato Muzika production house. (Mark, it should be noted, nearly died of COVID-19 in 2020 and has suffered lasting effects from the disease.)

Last year, Casale re-emerged post-pandemic with his first new music since 2016’s “It’s All Devo,” a single and video release credited to “DEVO’s Gerald V. Casale w/ Italy’s Phunk Investigation.” First came the “I’m Gonna Pay U Back” video, followed months later by a 12-inch 45 rpm Record Store Day EP featuring a new song, “The Invisible Man,” “Deconstruction” and “Instrumental” remixes and “I’m Gonna Pay U Back” in “Lounge,” “E-Z Listening” and “E-Z Listening Instrumental” versions. “The Invisible Man” video, featuring another remix, this one by Martyn Ware of Heaven 17, was released in late 2022. Both the “I’m Gonna Pay U Back” and “The Invisible Man” clips use the same AI processes, with the latter picking up where the former left off. None of this music strays too far from the band’s classic sound. If you’re a fan, you’re probably going to like it.

I spoke to Jerry Casale recently via Zoom.

I saw Devo for the first time at the Bottom Line in New York about 45 years ago.

Gerald Casale: Is that when I put a television on stage because the World Series was being played out, and it was like game seven, and everybody was bummed?

It was mid-October. I know that much. [October 17, 1978 was the first of Devo’s two nights at the Bottom Line and the seventh game of the World Series, in which the Yankees beat the Dodgers 7-2 to win the championship.]

Right, and everybody told me, “Hey, you better let this crowd watch the end of this game, or they’re not going to be into you.” I go, “Okay. I don’t care.”

I do remember it started out with the film, and that was great at the time. It was just something completely different, which was nice to see. I think halfway between then and now, almost exactly halfway, I interviewed you for an hour, hour and a half on the Pioneers Who Got Scalped compilation.

Oh, 2000, okay.

Yeah, we talked about a lot of that old stuff. I guess we either cover the last 22 years or just go for the current stuff right now.

Oh, boy. The current stuff, that could be days.

You put out a video and single last year, which was part of the EP. Before that, I think the last thing was in 2016. You haven’t been overly prolific, at least in terms of releasing material.

No. I just get very few opportunities to work with people, and I don’t have my own studio. Devo at one time had a studio, but that got morphed into Mark, and he’s only interested, of course, in composing. When we tried to collaborate in 2008 and ’09 on Something for Everybody, he had very limited interest. He would basically send files to my brother Bob Casale and me, and say, “What can you do with these?” That’s how that worked. So what I’ve been trying to do has never changed in terms of the spirit that made me create Devo in the first place and made me be an apostle of de-evolution, and come up with the name.

Devo was a multimedia collaboration and experimentation, quite innovative and original. That’s still where my focus is. That’s still me, and so whenever I get a chance to do that, I do it. Recently, for the first time in a long time, collaborating with Josh Freese, who is the Zelig of drummers, right? One week it’s the Vandals. The next week it’s Sting. The next week it’s Nine Inch Nails. And he can do it all, right? And he does it all with panache and perfection. Recently there’s been Steve Bartek from Oingo Boingo. Great guy, versatile guitar player, very smart and innovative and experimental, who loves to experiment. So it’s been fun again, and we’re doing more of it. So this is the tip of the iceberg, “The Invisible Man,” and there’s more coming.

So who is The Invisible Man?

Well, as I’m really stuck in this universe that we find ourselves in, of duality and darkness opposing light, and a Jungian kind of trope, the invisible man is the part of yourself that you try to bury. Of course, he keeps coming back until you deal with it.

Is this a theme that you’ve explored before?

Yeah, it’s been around a long time. I think maybe ever since “Peek-a-Boo.” That’s what was behind that.

So what made you revive it in 2022?

Because there’s a palpable sense of evil in Western culture like never before. It’s ratcheting up exponentially. I think everyone feels it, and it’s being played out in the political and social arena. It’s in your face every day. Just like the Supreme Court is a rogue Supreme Court suppressing the will of the people, it’s open season on reasonable people who mind their own business, who are law-abiding, who still adhere to the early kind of broad principles that brought America to where America was, which was, “Listen, you do what you want. I’ll do what I want, and as long as you don’t come into my front yard doing what you want, we’re all right.” Tolerance, liberty, personal space. That seems to be gone. What you’re looking at is basically authoritarian psychotic ideologues who aren’t going to be happy till they cram themselves down your throat.

Was this something you could have predicted?

Well, we did predict it, however it went way beyond what we were able to predict, and it got far worse, so it’s not funny anymore. I mean, Devo was satirical. There was a sense of humor. We thought we were canaries in a coal mine. We never really thought that what we are living in right now would come to be, which is basically an alternate reality nightmare as far as I’m concerned. That’s what it feels like. It makes me believe in the multiverse. Like, for real. We went through this teardrop time warp, and it looks like Earth, and those look like your friends. It’s like David Byrne, “This is not my beautiful wife.” It only looks like it did, but it’s not. The rules have changed, and something’s wrong. It’s cracked. It’s warped. It’s Black Mirror. We are living in Black Mirror.

So, the duality presents itself daily. The evil versus the good.

Yeah, it’s in your face and it ruins your appetite. I mean, ruins more than your physical appetite. It ruins your spirit. The people’s spirits are being crushed.

Making the videos for these two songs, who did you work with and how did you want to be portrayed?

I directed tons of videos, starting with the DEVO videos, and I was always using new technology whenever I could. I’ve never stopped being interested in that, and I’ve been really interested in these immersive VR experiences and these AI programs. My good friend, who I respect a lot, Davy Force, is like a whack genius. He’s like the character in Back to the Future, the professor, in real life. He was willing to work with me, and since I’m a songwriter and in the video, I welcomed the opportunity to lop off some responsibility. I wasn’t trying to be an auteur and direct myself. I had the concept, and I had a rudimentary shot list and storyboard. I collaborated with him and played off him and his insights and his take on it. We wanted to create something one step removed from temporal reality. We knew we had to go into that kind of Marvel Comics realm, like an animated realm. He had been playing around with these programs where if you shoot everything as elements on green screen and then assemble it, he can morph it into an animated look. Not that that’s never been done before, but it’s never been done quite like this before. We have a look here that is different from things you’ve seen in the past. Who was it? Was it Richard Linklater?

Linklater, yeah. [Waking Life, 2001]

Linklater that did that film in which he abstracted live action. That was an early attempt. It’s okay, but this is more entertaining, and more surreal, and kind of scary. I thought “I’m Gonna Pay U Back” was appropriately frightening, and the new one’s a little more fun, like the Teletubbies universe, but twisted.

Yeah. We see Teletubbies somewhere, don’t we?

It’s coming back. Yeah. It was a coincidence. It’s coming back, so I guess I was thinking right.

The guy who plays the sort of He-Man in the video is named Stan Weiner in the credits. That’s not really his name. I looked it up, and Stan Weiner is something from Noise TV. Is that right?

Yeah.

Played by somebody named Paul Vowell.

Paul Vowell is the CEO of 4D FüN in Culver City, which is a VR company that creates content for immersive experiences for the Oculus headsets. So that guy, who’s way, way out, that’s a real guy that I talked into becoming the Invisible Man. We put a green screen suit on him, and we let him wear what he actually wears to work minus the shirt. He’s all tatted up and… Oh, he’s perfect. I mean, he’s got a rap, too. He’s the perfect guy for his company, and he believes totally in the metaverse, and he’s a crypto junkie. It’s incredible. I mean, all the way back to the early DEVO films, we found non-actors, and we found people who were fringe characters in real life, and encouraged them to be themselves on cam.

Who was General Boy?

What?

Who was General Boy?

Oh, General Boy is Mark Mothersbaugh’s father. He ran an unemployment agency called Great Falls Employment where he would take people that had lost their jobs because of alcoholism and so on, or beating their wives, and he would get them entry level jobs and take a percentage of their wages. That’s how he built his fortune. That’s how he lived in the good end of Akron, and then he bought apartment buildings, and he had Mark managing them.

Was Great Falls a place, or was Great Falls sort of a humorous take on personal tragedy?

It was a building. He had the upper floor of an industrial building in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, not far from where he lived in Akron. When we shot the original 10-minute film The Truth About De-Evolution, that mural that Booji Boy runs in front of celebrating 200 years of U.S. Freedom, it was the 1976 200-year anniversary of the birth of America, that was Mr. Mothersbaugh’s building.

Wow. Amazing. That’s great. So much history.

Oh, yeah. It was like what John Waters did, right? All you had the money to do is form a troupe with your friends and associates and local talent who will work for nothing and build a myth out of it. Out of reality comes the mythology, and that’s what I was doing.

Talk a little more about writing the Invisible Man.

Oh, right. Well, what’s funny is a lot of these songs that I’m finally getting to do were things that Josh [Freese] and I spontaneously jammed on when he would drum with Devo on the few occasions sporadically here and there in any given year that Mark would allow Devo to play live. It would be Josh Freese coming and drumming with us. Josh and I had a lot of downtime at the rehearsal spaces we would rent, and he and I, still being excited about writing music, we would mess around to amuse ourselves. He would start these silly beats, and I would start just rapping vocals over the beat with no music. Then he’d go, “I like that,” and then he’d turn on his little device that he would record everything on, every idea he had, every riff he played. Then I would start playing the bass. He kept all of that in mind, and he saved it. He would bring up, “Hey, remember this one, ‘I’m Gonna Pay U Back?'” And I go, “Oh my God, I’d love to develop that,” because it was just a lyric and a beat.

I wrote a whole progression and then he worked with me on the instrumentation and the programming. We recorded it at his studio, and we worked with our engineer friend Paul David Hager, who has gone on to huge front-of-house [mixing] fame with Beck and Miley Cyrus and numerous others, and he’s a top engineer in the studio. So, we had a really good team of people that all like each other and are just excited to do something without having the promise of riches in mind, like when you’re first a band, and you’re not doing this because you think you’re going to get rich. You’re doing it because you love these songs that you’re thinking about. If you do something well enough, long enough, the hope is that, yes, it turns successful financially. I don’t have any illusions like that being a septuagenarian now, and I know how it works out there ever since I did put out things that you referred to.

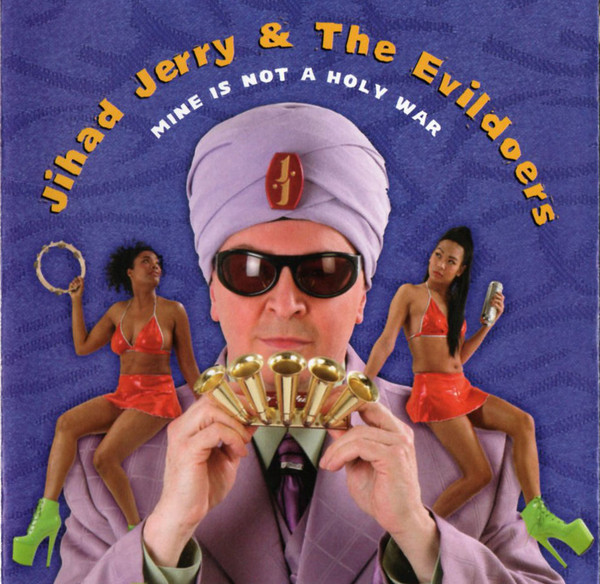

I was interviewed at SiriusXM in New York City, who really liked the stuff on the Jihad Jerry & the Evildoers record, especially the first cut, “The Time Is Now.” They go, “God, this is a great song, man. If this was a Devo song, we’d be playing the shit out of it.” I go, “Well, why can’t you play it?” He goes, “Well, Jihad Jerry & the Evildoers, there’s no way.” It was like, “Okay.” It would’ve been as simple as putting Devo’s name on it, had Mark allowed it. That wouldn’t have been far-fetched, because when Devo was Devo, we wrote about 80-percent of the songs together, co-wrote them, but I wrote songs he didn’t write. He wrote songs I didn’t write, but they were performed by Devo, and they were Devo songs. Of course, would I prefer that it wasn’t just Josh Freese, and it was everyone in Devo? Yeah, but that’s not a reality. I’m doing what I can now.

Is there a lot more where this came from?

Oh, yeah. All the way back to 2004, yeah, and newer ones. There’s a couple right now that maybe within weeks we’ll be recording. One’s called “West Virginia Boy” and one is called “Wetiko.” Rather than get into a long-winded rap about that, just look it up, anybody that reads this, W-E-T-I-K-O, and your mind will be blown, because in a way, this is a twin to the theory of de-evolution, and possibly something that’s bigger than de-evolution that could wrap itself around the de-evolution concept. And it goes way back.

You’ve given me something to do after the interview.

Yeah. Yeah, it’s an ancient Native American concept. That was their term.

So that’s kind of an analogue to de-evolution?

It’s about spiritual sickness at the center of human nature. Yeah.

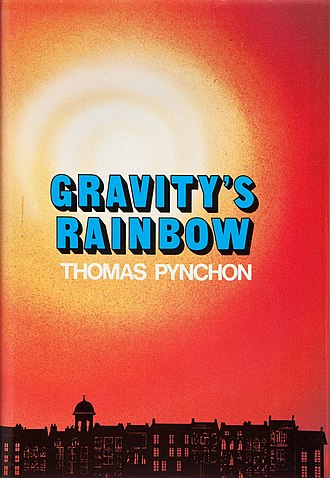

Do you have a favorite “Whip It” story?

“Whip It” came from four different pieces of music that Mark had created in his bedroom at different times and put on a cassette. They were at different BPMs, in different time registers, different instrumentation. None of it had to do with the song that got assembled. Of course, that was all assembled because of the beat. Once Alan Myers laid down that beat, I started thinking about those pieces of music, and how they could all be reconfigured and rethought as one BPM, and one set of instruments, and put together in a composition. I had written the lyrics to “Whip It” based on Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, where there’s a bunch of limericks in it, satire limericks, about you’re the only one, Horatio Alger kind of stuff. There’s nobody like you. You’re number-one. They’re hilarious, just skewering American hokum, right, and hucksters and con men. I thought, I want do one, and that was “Whip It.”

I didn’t realize Pynchon was behind that.

Oh, yeah. I couldn’t have done it without being inspired by that. Once the music started sounding interesting, I thought, “Oh my God, it fits. Those lyrics fit over this.” And back when we were the Three… well, the Five Musketeers, and I started putting them over the top of it, everybody responded positively and said, “Yeah, let’s work on that.” That’s how that happened.

But really the best story is the making of the video in one 16-hour day. And amassing talent from this local mart in Brentwood, California. Those were all people that worked at the Brentwood Country Mart — in a restaurant, at a coffee stand, at a creamery that made pancakes. The woman that gets whipped, she made pancakes. The girl that was cross-eyed, she served coffee — and she really was cross-eyed. The two waiters that are cowboys, they were waiters in the restaurant. The girls were waitresses, one was my girlfriend, that are in the corral, and the old woman was the one that owned the espresso stand.

I’ll never think of the Brentwood Country Mart quite the same. Did you ever get to meet either Allen Toussaint or Lee Dorsey after you released “Working in the Coal Mine?”

No. I would love to tell some apocryphal story where I got to, but I didn’t get to meet either of them. Bob Mothersbaugh and I really loved their music. Bob and I especially loved that early R&B and rural blues, and we loved “Working in the Coal Mine.” That was our idea to do that.

You mentioned that you’re going to be recording. Can we expect some new music from you soon?

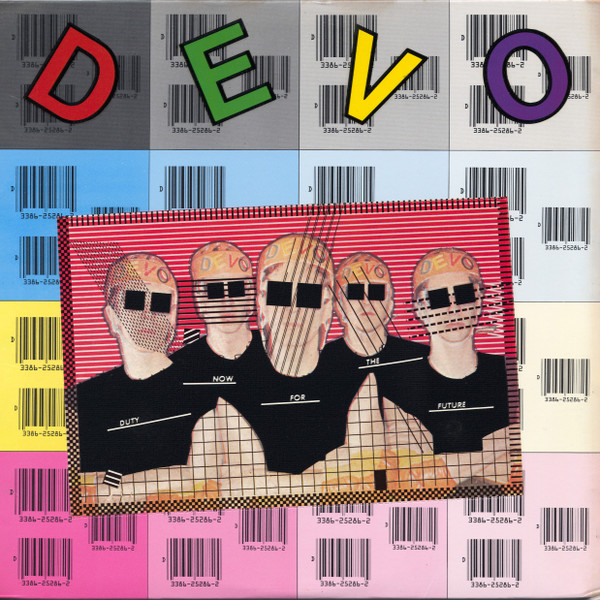

Absolutely. I wish it didn’t take so long, but I can’t even find a record label. I keep using Record Store Day as my drop and my launch, because that is a focal point, and I do respect that it’s all about vinyl. I love vinyl and I think the songs I write sound better on vinyl. I remember a time when vinyl was king, as we all do, and songs and groups put out… It was a piece of art. It was 12 by 12 inches, and it was a piece of art that you collected and revered, and the graphics, and the lyrics, and then you’d put it on the turntable. You’d be listening to the sequence that the artist had thought out, who said, “This is the way I want you to hear these songs.” There was no streaming. You weren’t jumping around, and that’s what I miss. I miss when music had value.

Any chance of doing any of these songs live at some point?

Boy, you hit it on the head. I would love to. I would love to go out with Josh and Steve Bartek and Josh Hager, who plays with Devo now when we do rear our ugly heads, and do it live. Absolutely. Oh yeah, and my nephew, who’s a fantastic bass player, my deceased brother Bob’s son, Alex. He’s an incredible bass player, and I’d rather just jump around stupidly and sing.

Why did you decide to do “lounge mixes” of your latest songs.

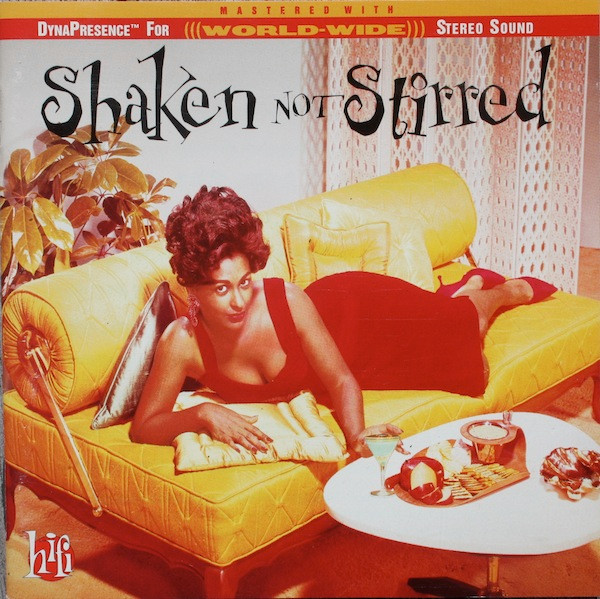

Jeff [Casale’s producer Jeff Winner] is an aficionado of that period, and of some of the greatest lounge people that clearly are beyond lounge, like Martin Denny, and is the head of a foundation devoted to it. I loved that music, too. Remember a CD that came out maybe, what, 30 years ago or more called Shaken Not Stirred? It was a compilation of all the best stuff.

Yeah.

That’s always inspired me, so when I got a chance to work with Jeep on this lounge version, it was fun. Then with Paul Vowell at 4D FüN, he shot Josh and me and Steve Bartek as a lounge act with two backup singer girls in VR reality in his VR studio in Culver City. We created a whole futuristic lounge environment and a whole audience of people, and it works. I don’t know what he intends to do with it, because it’s just sitting there. I entered that space with a VR headset, and it was so realistic and so effective that I almost got sick, like motion sickness, walking around in it. You can walk up to anybody and practically reach out and touch them. That’s the only time you realize it’s virtual when you reach out, and you can’t touch them, but you’re a foot away.

Is there another video coming?

Hopefully.