This article was originally published in Trouser Press Collectors Magazine, issue 3 (January/February 1979). It makes a logical historical bookend to the interview with his rival, Andrew Loog Oldham, from issue 1.

By David Fricke

Tony Stratton-Smith does not look like a guy who would regularly be seen in the company of card-carrying English eccentrics like Vivian Stanshall, Lindisfarne’s Alan Hull, any member of the Nice, the Genesis chaps, Bo Hansson (a Scandinavian entry) or Peters Hammill and Gabriel. But the well-dressed portly middle-aged entrepreneur of England’s Charisma Records is not only regularly seen in their company but has done his damnedest over the past 10 years to further the cause of their art by putting it on record and selling it with remarkably good taste.

The Charisma story — that is, the story of Stratton-Smith, a former sportswriter who became a label president through the avenues of music publishing and management — mirrors the rise and steady maturation of progressive English rock (a.k.a. art-rock) while providing a close personal look at the artists who make it.

Stratton-Smith is a willing storyteller. He’ll start with how he wrote the first book on Brazilian soccer star Pele, was commissioned by Brian Epstein to (ghost)write A Cellarful of Noise but had to turn the offer down because of previous commitments and then cruise into high-gear with hair-raising tales of near-bankruptcy in music publishing until he discovered management in 1966 with Paddy, Klaus (as in Voorman) and Gibson. They eventually went off into oblivion under Epstein’s direction, but Stratton-Smith hung in there, soon to make his first major score with the Nice.

“They’d just come off as backing group to P.P. Arnold, who had quite a big hit with ‘First Cut Is the Deepest’ (1967) on Andrew Oldham’s Immediate label. Keith put the band together, but Andrew didn’t really think of them as a separate act. Their usefulness to him was as a back-up group. Part of the condition on which they could record was that they find management, which is how I came on the scene.” (According to Stratton-Smith, the band took their name from an American source, the Nazz, as in Lord Buckley’s comic routine. “They were quite embarrassed when an American band emerged with that name, the Nazz.”)

“Keith was just getting into the quasi-classical thing with ‘America’ and I took over just before that single. We had awful headaches about the length of that single. It was 6:23 and couldn’t be edited. But Oldham — and I’ll say this for him — came up with an idea. He asked what the longest hit single was; at that time, it was “MacArthur Park’ at 7:20. So he said, “Okay, let’s put on the label that it’s 7:23. And nobody else ever bothered to time it. With the band touring, it broke into the Top 20 in Britain on minimal airplay.”

While handling the Nice, Stratton-Smith took on management of the Bonzo Dog Band in 1968, later that year adding Van der Graaf Generator to the list. “Mentally, the Bonzos were a collection of chaotic talents and they created this incredible thing between them. But they never really thought like a band; they all fought for their individuality. Like Legs Larry always had to have more sequins than anybody else. But that was easy — nobody else liked sequins.

“What they needed — and they got it in England — was a steady success. But in America, they didn’t get it. The Nice were hard-nosed professionals. The Bonzos did it because they enjoyed doing it. And the minute it started becoming a nightmare, they decided they’d had enough.”

On Van der Graaf: “If I’ve felt any pain at all about my artists, the greatest pain has been Van der Graaf Generator. I truly believe Peter Hammill is one of the best lyric writers in the world. I also caught on fairly early that he’s almost anti-music. Peter almost deliberately — every time he comes close to being accessible — shies away from it instantly and runs off into a more impenetrable realm. The greatest problem is that if Van der Graaf had had more success early on — as he kept raising this threshold, a lot more people would have followed him and it might have worked. But he’s gone through all the changes of a successful artist without taking the original following with him. That is probably why he’s one of the most interesting artists around and I don’t know what the hell to do about it.”

Among Stratton-Smith’s other clients were Beryl Marsden (of Shotgun Express) and the Creation, of whom he was particularly fond. He enjoys telling one story of how the band opened for the Walker Brothers one night on a show at which they tried a bit of op-art during one of Eddie Phillips’s long guitar breaks. “The singer, Kenny Pickett, would have nothing to do during these solos, so we came up with the idea of building a frame, covering it with paper, and during one of Eddie’s solos, Kenny would introduce ‘action painting’ with aerosols.”

What got the hall management and the Walkers’ people upset was that, at the end of the song, Phillips set fire to the painting, an illegal move that practically got the Creation thrown off the second show. Stratton-Smith cooled things out, and the band went on again with the action painting gimmick. “But Eddie got carried away again, set fire to it, and we were forever banned from West Yarmouth.”

Needless to say, handling as unstable a stable of artists as the Nice, Bonzos, Van der Graaf, and the Creation gave Stratton-Smith record company headaches he didn’t need. However, these aches and pains were not the cause of the artists but of the labels themselves. According to Stratton-Smith, Oldham’s Immediate label did no great favors for the Nice — during the filming of an NBC-TV special in California, the Nice could not get Immediate’s New York office on the phone because it was on an answering service for a week. United Artists in the States was particularly uncaring about the Bonzos and, as for Mercury’s early contract with Van der Graaf, they gave the band a full two days to record The Aerosol Grey Machine. “And even then,” says Stratton-Smith with clear sarcasm, “they thought they were doing us a favor. It was probably two days Rod Stewart didn’t use.” Stratton-Smith also had troubles with English Decca when he got Al Stewart — whom he managed for a time — into the studio to record his first single, “The Elf” b/w the Yardbirds’ “Turn to Earth.”

At the same time he was mulling these label nightmares, Stratton-Smith was approached by a retail distribution chain, B&C Records, who were literally begging for business. The idea of an independent distributor appealed to Tony Stratton-Smith, so he agreed to go ahead with a label of his own. The name Charisma, oddly enough, came after Tony Ashton (of Ashton, Gardner and Dyke) asked Stratton-Smith, who had managed his band, the Remo 4, to come up with a name for his new group. Stratton-Smith offered the name Charisma, which Ashton turned down because he didn’t know what it meant. “Later,” laughs Strat (a frequent nickname), “I was really grateful to him because if he had taken it, I would have had to call the label Ashton, Gardner and Dyke.”

As a label president, Stratton-Smith combined business acumen with a bit of the old tongue-in-cheek. He modeled the original label logo after an inscription on a turn-of-the-century pub mirror (the Mad Hatter came later) and released the first Charisma single, “Witchi-Tai-To,” in December 1969. A cover of the Jim Pepper-penned pop-Indian chant that was popularized in America by Brewer and Shipley earlier that year, it was recorded by ringmaster Legs Larry Smith and his circus of Bonzos, various Who and other associates under the pseudonym of Topo D. Bill (the Bonzos were still signed to UA).

“For this masterpiece of a single, Larry insisted on either ‘Witchi-Tai-To’ or ‘Springtime for Hitler.’ We were just closing a deal with a German distributor, so we didn’t think ‘Springtime for Hitler’ would be all that good and went with ‘Witchi-Tai-To.’ I also remember that single because we were counting every penny in those days. I said to Larry, ‘Well, you’ve got your studio and musicians. What else do you want?’ He said ‘I’ll tell you, old boy, if you could arrange for 44 drumsticks of chicken and a dozen bottles of champagne…’ ‘I told him he had to be joking. ‘No, no,’ he said, ‘we’ve got to have a supper break.’ And like an idiot, I fell for it.”

Charisma’s first longplayer, Rare Bird’s debut LP, Rare, was released on December 3, 1969. It was selling well on the strength of the band’s tour until Stratton-Smith, against group-leader Graham Field’s wishes, released “Sympathy” as a single after Christmas. That single literally made Rare Bird and gave Charisma a steady source of income through the better part of 1970.

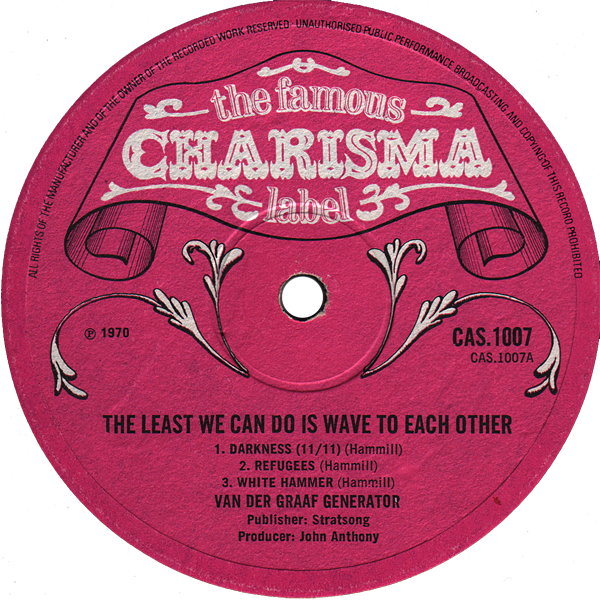

Two other incidents occurred in the first six months of 1970 that put Charisma on steady footing. The Nice split up in March and “as their farewell present to an elderly manager,” licensed Five Bridges to the label for release. Shortly after that came Van der Graaf’s The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other. Both were steady sellers and were soon licensed to American labels (the Nice to Mercury, VDG to ABC affiliates) who showed interest in specific acts. And not too far behind lay late-1970 releases by Audience (Friend’s Friend’s Friend), ex-Nice-ees Lee Jackson (Jackson Heights’ King Progress) and Brian Davison (Every Which Way), Lindisfarne (Nicely Out of Tune) and, most importantly, Genesis (Trespass).

Stratton-Smith first heard about Genesis in early ’70 through Rare Bird’s Graham Field, who made a passing reference to the band and an opening gig they did with Rare Bird. Field didn’t go out of his way to help Stratton-Smith find out too much more about Genesis because, as a member of the label’s leading act, he felt Charisma was signing too many new bands and therefore distracting promotional attention from Rare Bird. Incensed by this, Stratton-Smith went out of his way to track down Genesis, got Peter Gabriel on the phone (“The guy sounded so disorganized…”) and a tape out of him, later catching Genesis at the upstairs room of London’s Ronnie Scott’s with all of a dozen other people. The band so knocked him out that Stratton-Smith had a deal with them before the night was out.

“There are certain bands you see just once and they get so many areas of your mind stimulated. They had it all going that night. In a way, I think the timing of it was right. I was hungry for a band I could really be proud of and they were looking for a manager they could rely on. And they had some astonishing attitudes, foremost among them the belief that they would never make it as a live band. And here we are —today — for the second year running, Genesis have been voted the best live band in the world by Melody Maker readers. Genesis really felt that they would be writers, spend as much time in a recording studio and remain a mystery beyond that.”

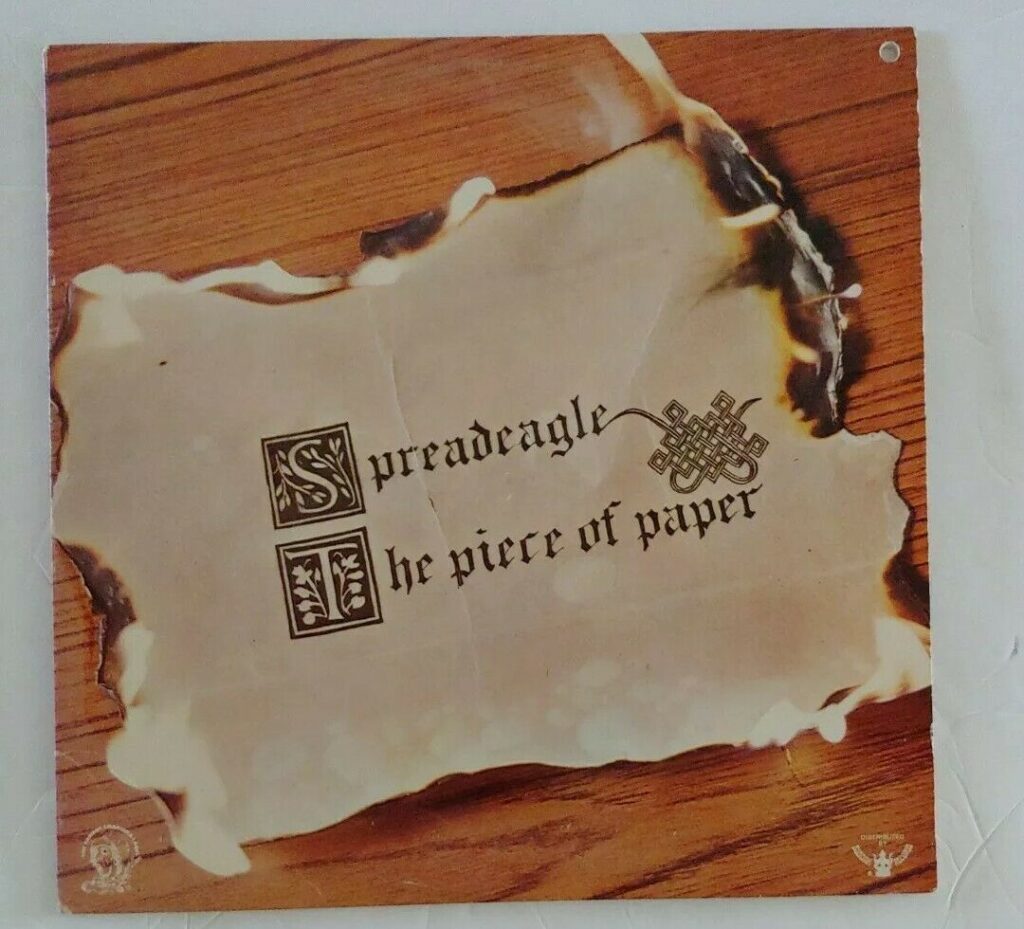

Charisma’s first few years were amazingly successful ones, especially for a label as fiercely independent as it was. But a look at the Charisma catalogue shows that there were just as many (if not more) misses to keep things interesting. Singing schoolmaster Clifford T. Ward had a couple of English hits at 45 rpm, but his inability to give a credible concert performance hurt his larger commercial chances. Singer Graham Bell recorded with the band Arc, made one decent LP, toured the States with the Who, then returned to England and fired the band — without bothering to tell Stratton- Smith, who had initiated the pairing. There was also Spreadeagle, who released one Shel Talmy-produced album in 1972.

“I think, in a way, you can be proud of certain failures, and Spreadeagle are a classic case. When I first saw them, playing in a little bar in East London, I got hooked on two songs. So I signed the band, started to work with them and a year later that’s all they had — two good songs.”

There are also artistes few have even heard of who issued Charisma product. Consider these names: ex-Blue Cheer guitarist Leigh Stephens, the Osibisa-like Jo’burg Hawk, Italian art-rockers Le Orme (Felona Saroma), the deservedly obscure Hot Thumbs O’Reilly (actually Jim Pembroke, lead singer for Finland’s Wigwam), Doggeral Bank, Darien Spirit, Sir John Betjeman (of whom Stratton-Smith is rather proud), Australian crooner Gary Shearston and the Dutch Concertgebouw Orchestra, whose Life Story of Mahler must have paid [a] few bills.

Needless to say, few of these albums or singles made it Stateside. But Charisma made two important stabs at penetrating the American market with distribution deals involving, in 1972, Buddah and, in late 1973, Atlantic. Buddah helped break Genesis in America on the strength of Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot and a daring promotion that brought Genesis to New York for a one-off show in December of ’72. Staged at the prestigious Philharmonic Hall, the Genesis Christmas benefit show presented by WNEW-FM and Charisma at a cost of $16,000 was an unqualified success to everyone but, ironically, the band.

“Genesis were against it at first and rightly so; it was a difficult thing for any band. But I had a problem. Genesis had already arrived at a point in their presentation that it took them so long to set up and strike the set that they could never be a support group.

“The group always felt the Philharmonic show was a partial disaster because on the day of the show, Leonard Bernstein suddenly decided he was going to rehearse the Philharmonic Orchestra, so we couldn’t get into the hall to set up until four o’clock. In fact, the band was still having its sound check when the doors were opened. The sound wasn’t perfect, there were a few flaws, and the band was almost in agony. They felt they were terrible. But I told them afterwards, ‘I know you weren’t 100%, but they don’t know and 75% is better than they’ll get from most bands.”

The key to Charisma’s success — and, of course, Stratton-Smith’s personal success — lies in his triple crown as label prez, manager and psychologist. As in the aforementioned Genesis case, Stratton-Smith maintains a direct personal pipeline with his artists, particularly the difficult ones like the two Peters, Hammill and Gabriel. He admits that, when Peter Gabriel announced his leave-taking of Genesis, he spent many hours trying to dissuade Peter before finally accepting and respecting his reasons for quitting. He also says — in reference to the likewise publicized departure of Steve Hackett for solo pastures — that Charisma doesn’t even need an A&R man. “We can just sit back and wait for Genesis to form a new band.”

Charisma, in fact, has had only one Artist and Repertoire man until this year — and that was Stratton-Smith himself. He signs the bands directly and takes a hearty artistic hand in determining what goes out of the office with a Charisma label on it.

Singles, he says, were never Charisma’s strong point simply because he saw no need for them. Charisma was selling albums in copious quantities and those albums were by groups that English and American radio chieftains saw only as album acts.

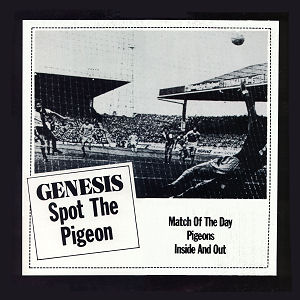

“The use of B-sides that weren’t otherwise available” — a reference to Genesis collectors’ items like “The Waiting Room” and “Happy the Man” — “was really a ploy in the early days, especially with Genesis. Genesis never had any real acceptance as a singles band, so the use of an unreleased or live track on the B-side was simply to get the Genesis following to support the single in its early days. And it worked, certainly with ‘I Know What I Like’ (backed with “Twilight Ale House”‘) and the Spot the Pigeon EP. “Spot the Pigeon made the Top 20 in England and we weren’t even on the bloody BBC playlist.”

Genesis’ more recent “Follow You Follow Me” is the label’s all-time 45 rpm best-seller, closely followed by Clifford T. Ward’s wistful “Gaye.” In the long-playing sweepstakes, the winner is again Genesis with …And Then There Were Three.

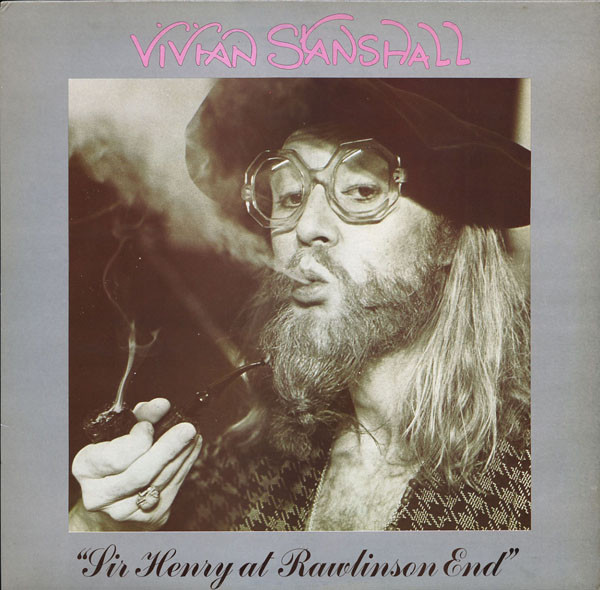

On any aesthetic or economic scale, Charisma is clearly a successful example to be considered in any examination of independent labels in both England or America. Growing out of a British tradition established by Andrew Oldham’s Immediate, Giorgio Gomelsky’s Marmalade, EMI’s in-house indie Harvest, the Who’s Track, and John Peel’s defiantly non-profit Dandelion, Charisma has survived its first 10 years in style. Any label that can sell Monty Python records to Americans who barely understand the jokes, that can release records by a Swedish recluse like Bo Hansson who they barely see in person for six months at a time, and that can issue a new Vivian Stanshall album (Sir Henry at Rawlinson End) in an attempt to make him a star “much against his better judgment” need make no excuses for itself. Walking away with over a dozen artist awards in the recent Melody Maker reader poll is only icing on the cake. To what, then, does Tony Stratton-Smith attribute his winnings?

“It’s all time, space and the moment. And if the moment’s there…”

…the rest must be easy.