Interview by Dave Schulps

Let’s talk about how what you were seeing in Trouser Press and other mid-‘70s independent media affected your and Jake [Riviera]’s decision to start an indie label like Stiff.

That whole early ’70s period in the States, Trouser Press and various other periodicals had a big effect on me and Jake separately. Jake was very impressed with the independent labels of the indie period. England was very into the majors thing, the satin trousers and the high heel boots and the haircuts and whatever, and it needed something — it was pretty boring. At the end of the day, you could not really get excited about these people. They seemed to be kind of faceless, they seemed to be part of a corporate image, even though they looked slightly interesting, their clothes weren’t very trendy. They weren’t very cool. And, yeah, here was a lot of America that we absorbed in order to make our point.

How did you and Jake Riviera first meet?

I don’t know if he would agree, but he always stalked me a little bit. I was out there doing stuff, putting together package tours and various other things because I’d learned it, as we discussed, in the past. I liked the idea of [presenting] three bands, I liked the idea of there’d being no fat, that the band would go on very quickly, their sets would be very streamlined. It was not boring. It was worked up to the nth degree that everything would work. And Jake copied a few of those. He had a band called Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers, and they were like a take on Brinsley Schwarz, which was the best band musically and Nick Lowe was probably the best writer.

And so we came up with a slogan at that time: “We lead, others follow, but can’t keep up.” Jake went to America for a Dr. Feelgood tour as a tour manager. And they were so good. Lee Brilleaux was fantastic. They were real happening guys, and they had a great time. So Jake came back with a lot of ideas. And I had spent a couple of years getting the studio together, getting the tapes, getting bands sorted out, [recording demos with] Declan McManus [among others]. I had also discovered Graham Parker, a very crucial cog in the whole thing. And he was doing very, very well. Members of several bands playing behind him; it was a bit of a supergroup really, or felt so at that time, and fitted into Trouser Press‘s idea, Creem, those kind of magazines. The UK had five weekly papers on the street, music papers, and they needed quite a lot of stuff.

So Jake and I talked about it. He had come back from the Feelgoods tour, not with any money or anything. I had an office, I had a telephone, I had a load of tapes in the corner that were only waiting to be mixed by somebody and put on the street. So we decided to get together. Jake [is] fairly bigoted individually, not fond of Irish people — actually, he doesn’t like anybody, really. So we had a few good arguments and good rows. Jake managed Nick Lowe now. And Nick was a crucial cog in making the tracks. We found a little studio, there was an eight track and Elvis’s album, My Aim Is True, his opening gambit, was made there for, I think, 700 bucks or whatever, with Clover, a band from Marin County as the backing band. Huey Lewis was the harmonica player, but there’s no harmonica on the record so he didn’t get to play.

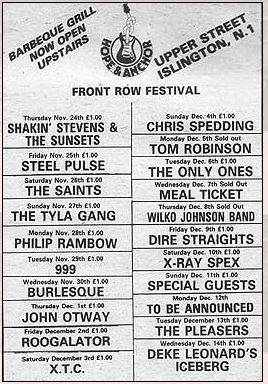

It was that kind of time. There was a lot going on. There were lots of clubs. There were lots of pubs. There were lots of below-the-line underground things happening in the UK. Jake and I both hated the major labels to such a degree that we just loved the idea of winding them up quite a bit. So we came up with the slogans.

People say, how come you were able to do certain things and present certain musical outings and the majors either weren’t interested or couldn’t do it? I’ve explained that they had one slogan and still have the same slogan. I think slogans and what you say about music is very important, other than it’s like that, or it’s like Robert Palmer, or it’s like this, or it’s like that.

I think if the music is describable like that, it’s not worth proceeding with. And so the slogan that the majors had, which they used forever, was one and every album had the same slogan, “Out now.” So we came up with all the other varieties. We had Barney Bubbles, who I discovered. Eddie Moulton [one of his Famepushers business partners, see Part 1] actually had formed a little company for Barney’s graphic design in the very beginning — one of the companies he moved that five grand through.

Oh, I should tell you that at the end of New York [the Brinsley Schwarz Fillmore East debacle discussed in Part 1], when I got back from the trip, I went out to LA to talk to United Artists. The band came back to hell-hath-no-fury negative press. I came back and, of course, everybody wanted to be paid, the charter plane company, the limos, the blah, blah, blah. And it turned out there was no money at all in the bank account. Eddie [Moulton] had run off with it.

Eddie had disappeared along with my car and all the money in the bank account. Luckily, at the time, having worked for Hendrix for a while and learned my gig from Mike Jeffery, I had made a point that the bank needed two signatures to take any money out. And they hadn’t asked me for mine. So Famepushers was no more, but they had to reimburse me and so that sorted things out. The bills got paid, the band took off. Eddie, at this point, had disappeared. [Famepushers co-founder] Steven Warwick’s house was nearly sold, because Eddie, it turned out, had mortgaged it without telling him. And so it was a disaster from that point of view. Nobody has ever discovered who Eddie Moulton was. He was Canadian is all that most people knew.

Stiff got going because of John Peel, who was a DJ in the UK and had the — I don’t know how he did it, but he got the clout to be able to play anything he liked, very like FM in America. He was able to play what he liked. And he liked Stiff, he liked Nick Lowe. And he had been a DJ at all the benefit festivals we’d played — with the Grateful Dead, Bickershaw [a three-day festival held near Wigan in Lancashire, England in May 1972]. ‘Cause having done the New York journey, I booked the band into every known benefit festival…If you had a cause, we’d get out there and play. And it had a good effect, because John was the DJ in all those places. And so while not really appreciating it, I was building a good situation with him.

Jake? Very clever, Jake. Clever advertising, real good ad man. I describe him as, “He liked to burn the bridge while you were standing on it.” That was his favorite saying. The five newspapers were easy game for us, because they needed content every week. And that came from whatever you dreamt up. There was a perfect example of what to do. There’s a few of the early managers where we used their influence to do stuff that nobody else was bothering with.

Was all this planned out or, or did you just do it by the seat of your pants?

We had a meeting every day where we walked around the block for about an hour and that would form the day’s [agenda]. So, no, it wasn’t planned. Changing Elvis Costello from Declan MacManus, I came up with the glasses, Jake came up with the Elvis and I was just totally amazed that Declan went for it. I thought there’s no way he’s going to agree to this, but he didn’t blink at all. And he still doesn’t blink. The amazing thing is he’s still going. He still looks like a Stiff artist. He still does what he does very well.

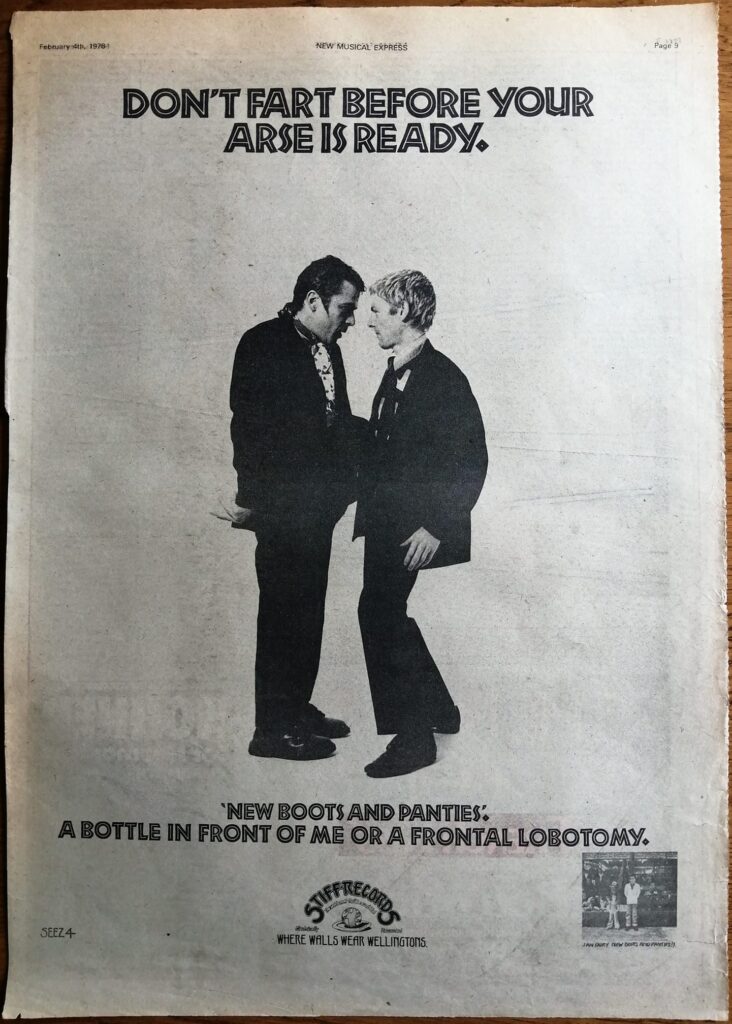

Ian Dury was a perfect example. Two great slogans for Ian, one was, “Give up smoking and give us your money.” That was a good one. Then the second one was, “Don’t fart before your arse is ready.” That caused a bit of a conflagration in the charts. I think we sold 40,000 albums that week that we put that slogan out on double-page ads.

The audience was used to looking at the music papers: reviews and press people and the stories of the road and the trips to America and the mayhem, all of that was part of the rock and roll story that people really liked and adhered to and were affected by it. So Stiff got a very good name. And we put out several package tours, which were fun and did great business. Also, the UK universities were great help. You had John Peel on the radio and then touring with the universities where people on their holidays would go home all over the country, taking the word of the great gig…we were putting on really good shows. So it was very much a family, and everyone was together, and it worked very well till Jake left.

I remember Dave Edmunds said that Wreckless Eric walked in with a rehearsed speech: “I’m one of these guys who does this or that.”

That’s exactly what he said. He was very drunk at the time. He’d drank two very large flagons of cider. And we had a bad step at the doorway. So when you went to come in, you fell in, because you tripped over the step. So this is one of the guys who tripped over the step and said, “I’m one of those guys that comes and brings tapes that you probably won’t like to the record companies.”

What was very lucky was that Nick Lowe was in the office that day. And when Wreckless left, people were laughing at the character of him. He wasn’t called Wreckless, he was called Eric, Eric Goulden. So Nick slammed the cassette into the player. The office had two very big studio monitors and this incredible “Whole Wide World” — two chords, punky voice — came pouring out. And at which point I ran into the street to try and catch up with Eric. Luckily, he’d put his number on the tape, so we did get in touch. But that song [was used by Expedia] recently, I don’t know if you’ve noticed it.

Oh yeah, seen those spots many times.

Yeah. Yeah. So it’s added a lot of new fans. He’s earning well, Eric, he’s married with a new partner [American singer-songwriter Amy Rigby]. She’s very punky and he plays the miserable old git, which he’s always played very well. And it’s an attractive pairing, I think.

That’s great. The Damned, who brought them in? Who decided Nick would produce them?

Jake discovered the Damned. [Skydog Records founder] Marc Zermati, I might be wrong, but he had discovered them. Jake went to a festival in France to see somebody else. I think. I don’t know, Richard Hell I think played there or someone like that, American. And he saw the Damned and thought, fantastic. Marc was a very big fan. And, of course, we put the very first punk album out and the first punk single, “New Rose.” Still sounds as good as ever. And that’s how the Damned came to Stiff.

They were much better than anybody else. A lot of the other bands really couldn’t play. It was very raw. It was raw to the point of, I don’t quite know how it happened, but it looked great. Ian Dury was a very early punk, really. He had the safety pin in his ear long before Johnny Rotten or other people. People looked at him and he was very punky. Art school — he was a teacher at the Royal College of Art. He’d studied there with Peter Blake, the guy who did the Beatles cover [Sgt. Pepper’s]. And so there was so much going on. It seems now that there was a period when so much seemed to be revolving around the media, the magazine, the radio shows the stuff that it was natural that the music was needed to fill it. And we have a lot.

Motörhead only had the one single on Stiff. Did Chiswick steal them from you? What happened with that?

Lemmy was very miserable at the time. He went on to be, I wouldn’t say a close friend, but a close compadre and a really good bloke. But prior to that, he was very scathing. He didn’t like record companies. He didn’t like anything. He thought Stiff was a stupid name. He had his own attitude to it. And so we only got bits and pieces of Motörhead’s input.

Lemmy, he went to the gigs, he loved the Pink Fairies, he liked some of the bands and he would show up. He’s a huge pinball player. He knew every pinball machine in London and spent most of his waking moments absorbing some substance or other and playing the machines in pubs until the late hours. Yeah. A good man, Lemmy. We’ll miss him. He did survive a lot longer than people imagined.

Did you have high hopes for Plummet Airlines?

I can’t say, to be quite honest. I think Plummet Airlines were one of Jake’s signings. Although we all signed them together, we had various favorites and they weren’t one of mine. They went with him when he left to form Radar, so we didn’t have the ongoingness of Plummet Airlines.

Then they fell off the radar, I guess. And we never heard from again.

That’s right. Fell off the radar. That was good, yeah. There was a lot of quotes of that nature. Yeah. Very like Rob Dickens who used to run Warner Bros., but he started a company called Instant Karma and never saw another hit. Anyway, there you go.

How did you and Jake finally end it? Was it just too volatile? The two of you?

No, I thought it was going really well at the time that he left. It just surprised me, really. I don’t know if it had to do with the fact that Columbia had offered us half a million dollars for Elvis’ contract. That might have had something to do with it. The main thing from my point of view was I gave them Elvis, because we needed to split it up very quickly. Jake and I are both quite volatile, and I knew that that it wouldn’t work if it became a drawn-out fight of some kind. Also, Jake appointed the bookkeeper at the office, and I went through his desk the night that Jake told me he was leaving and found 150 grand worth of receipts stuffed into drawers that had never been filed or been dealt with.

I got a feeling that he thought that was the end of it, that him leaving was the end of Stiff. And I’m not that easy to shift, really. I’m just as persevering as anyone. And I thought Ian had some great stuff. I didn’t think the public had actually caught onto him. And I thought we could do something more with him, really. I had a chat with him, and he said, “I’m with you.”

And so Elvis, still friendly to this day. Good bloke. Jake told him what was happening and that he expected Elvis to go with him. I had his management agreement — he was actually signed to me rather than Jake — I was his manager, but I gave the paperwork over and said, “I want everything done, though, by Monday. I want a settlement document by Monday. This is Friday. I want us to be parted cleanly and legally by Monday, and to do that, I’m prepared to negotiate.”

Did you sign Madness?

Oh yeah. Yeah. Madness…

All of a sudden, you became a video director when they walked in the door.

Well, Madness, a good example. Several people had suggested to me that they’re a band that I would like, a lot of people said they were very influenced by Ian Dury. And I couldn’t sign them because I hadn’t seen them. You have to look at the band before you sign them. And I was getting married. So I thought I could kill two birds — well, that’s the wrong expression — that I could deal with two matters at once. So I booked them for my wedding, so that way I could see them. And they played a very good set.

I heard the track “One Step Beyond.” My wife said, “Will you pay attention to me and not the bloody band?” Et cetera. But that was when it came to me in a flash that this was the name of the album and the name of the first single and the band didn’t agree. So it took a bit of touring and throwing to get that sorted out.

They were great. The videos, we had a guy called Chuck Statler, do the very first video. And Chuck was from the States. He very good, but he had one simple idea of how it went. So I copied that. I looked over his shoulder and thought, “God, he does the same thing every time, I can do that.” Also, videos at that time, before MTV, were used mainly to send to your licensees in Australia so they could see the band that you were signing and hopefully take part. So they were a tool for the licensees. Then MTV came on the horizon. I saw that, and I learned to make videos.

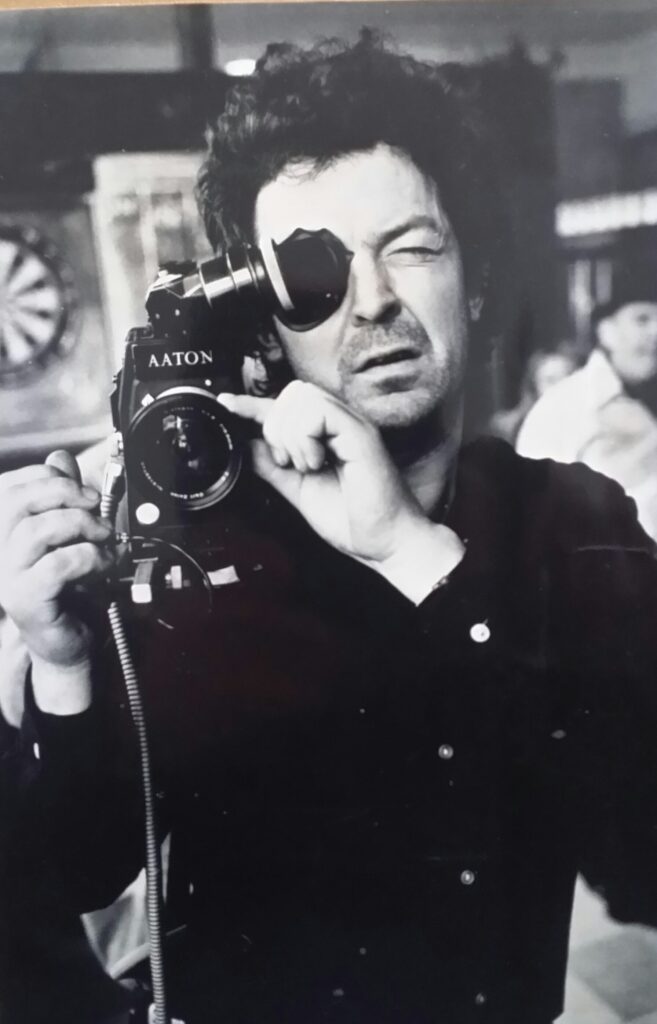

Photo courtesy of Dave Robinson.

All those videos were made in one day, because I couldn’t take any more time off. And my wife edited quite a lot of them, so it was in the family. And Madness were natural actors. At the end of the day, they could make anything look normal, any wildness look simple. I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie Take It or Leave It, but it’s worth looking at it, it’s the story of the infant Madness and how they came about. And they’re great in it. It is a good movie.

Yeah. Actually, I want to double back, because the question I was going to ask you at the end, right before I asked you about Madness, was, did it hurt that Nick Lowe left with Jake, considering that you went back a long way?

No. Nick Lowe, every now and then he would give me good credit and says, I taught him everything he knows. And I did. I didn’t teach him to write songs, but I taught him everything else. I took him in the studio. I took him with me at Brinsleys. It was like all those Hendrix and photography experience and all that early stuff that I was lucky enough to be doing without particularly planning it. All that stuff I took Nick and over the four years of the Brinsleys, we pretty much debriefed each other. We are friends, and I knew what he could do. I gave him the first Graham Parker album to do. And that really was his first production, in actual fact.

The thing is, we had an eight-track studio called Pathway. We didn’t have it, but we used it. And Nick’s attitude was to rehearse the band so they know the songs and then go in studio and put it down quickly, and put a few echoes on it. “Trash it down and tart it up,” was the mantra that he used. And I approved of that, that was my idea of how production goes really. And a lot of the music that I like, and probably you like to a degree, all that early American stuff in Philadelphia and all the various bits that the punk elements of CBGB and whatever, the Pretenders and Blondie, all that stuff all came under the same umbrella. And Nick did it very well.

Did your photographic background help you when you started directing videos?

Oh yeah, very much so. The photography… I worked in Ireland for a magazine company who had 40 magazines. The big one was a magazine called Creation, which was essentially Irish Vogue. So I did a lot of fashion there, but they also had Veterinary News. So on a Thursday, I might be taking a picture of some vet with his hand up the rear end of a cow, trying to make that look attractive as well. So my experience was very broad. And they had a couple of bicycle mags, they had motor mags, so I had a very broad photographic thing. And that whole period, that early ’70s period, quick recordings, like a demo quality recording, photographs that were quickly done with motorized cameras. So we took a lot of pictures, a guy called Chris Gabren.

There were a few people very much throughout that were exceptional and useful and quick. My mantra was “now.” I had a big clock in the office that had “Now, Now, Now, Now, Now, Now,” for every number on the face. I had a motto that I would tell people: “Nothing’s impossible, as long as I don’t have to do it.” It was all the things that you’ve done as well, Dave, it was a great period when we were stars in the sky, really. We were flashing lights and it was a worker. It was a great period.

How did you end up producing videos for the two Roberts, Plant and Palmer?

Well, there you see. People saw Madness videos and thought… And also, it’s the kind of video that you talk about. Robert Plant’s video, he told me that he wanted to drink champagne all day and he wanted a lot of girls in it. So it wasn’t too difficult for me. He was just pissed off when the girls left at seven o’clock, because he thought he’d pulled a few of them, Robert Plant.

Robert Palmer, he was a friend and a natural, he was a natural singer, natural in the suit in the look. You could do anything around him. And so, there’s a lot of fun. I did a Deep Purple video, and I did quite a series, essentially for money. I’m a vegetarian to a degree, but ,I did some meat commercials, because they were very highly paid.

Just have a closing Stiff thing, which is Tracey Ullman, because that’s an unusual story. And, I guess, Kirsty MacColl as well, whom I understand you did not really get on with.

Well, I got on fine with Kirsty. I got on well with her. She was very suspicious of, I wouldn’t say men generally, but of business men, record company executive kind of things. Her dad, [English folksinger and songwriter] Ewan MacColl, had run off in the night, and I think her mother had colored her against fast talking men with dark hair, of which I was one. But we got on fine. We got on good. She left Stiff to go to Polydor for the check. And we took her back. We took her back because she was so good. Also her songs… My wife went to a hair dresser and the lady in the next chair [turns out to be Tracey Ullman and] is saying, “Oh, I’d love to make records. It’s something I’ve always wanted to do. And my wife just leaned over and said, here’s my husband’s number if you want to make records. Why don’t you talk to him?”

And we had those Kirsty songs. They hadn’t been hits for Kirsty. They’d done well, but they hadn’t been big hits. So enter Tracey, who couldn’t sing quite as well, but had more of a TV persona. Kirsty had terrible stage fright. She didn’t like appearing. She didn’t like making videos. She didn’t like going on TV, which at that time were all the promotional tricks that you had to use. And she didn’t like any of them, but Tracey loved it. She was in her element if she was on TV, and she had a lot of tricks. We put her in America, she got into MTV as a VJ for a couple of months. And that really made her. America took to her big time.

To end the Stiff saga, how did it end?

It ended in 1983. Stiff was doing great. Moved into a new office, and we just signed a band called King Kurt that I really liked. Chris Blackwell [Island Records head], who used to distribute the label in the early days, he was very helpful. I got on very well with him, but he was called “The Babyface Killer,” and it turned out to be an apt name. He kept harassing me to run Island. And I said, “Well, I’m quite happy where I am, Chris. And everything is fine.” So he came back three or four times, and finally told me he would buy half of the company, and I could decide how much it was worth. That was attractive.

So I asked him for two-million pounds for half of the company. We had a lot of money in the bank, and everything was very good. In fact, we’d got onto a bit of an even keel with Madness and various other things. So he challenged me to do it. He also wanted to possibly sell Island later, he told me, and he would give me a very big bite of that. One of the things I liked, he was a big fan of Bob Marley, and so I now had that. He talked about doing a greatest hits anniversary sort of thing. It turned out that he had already done a couple of albums when Bob died anyway. He kind of lied to me a bit and said nothing has been put out.

I knew Island, but I wasn’t really paying attention to them intimately. But Frankie Goes to Hollywood — I knew Trevor Horn and I knew that record “Relax,” which I thought was quite extraordinary. So the idea of working with them appealed to me. I had a few ideas of what would make it kind of shift. It was stuck about number-60 or 70 in the chart and had been on the radio quite a bit, so it was starting to fade. It had been on too long. So we decided, “Okay, he’s going to buy half the company. He’s going to sell the two companies together, down the road. We’re all going to do very well. It all sounds okay.” So I had a chat with the wife and we went ahead.

So, Frankie Goes to Hollywood. I’d been in New York and there was a Trevor Horn-made 12-inch called “The Sex Mix,” which is an obvious possibility and actually very good. So I put that out over Christmas. So I went to the Island people and said, “Nobody’s got a holiday over Christmas. We’re all going to work because we need to get this record going.” And it jumped bigtime. Eventually, a DJ threw it at the wall during the breakfast show and said, “I’m not playing this crap, blah, blah, blah.”

A guy from the BBC, Ted Beston, called me and said, “We’re banning the record, Dave.” I said, “Ted, how can you ban the record? You’ve been playing it for three months as a C-list, kind of.” He said, “Well, it’s all about ejaculation.” I said, “I think if you look at the charts, you’ll find that there’s a quantity of records that you could put under that heading.” He said, “I don’t care. We are banning it.”

So I said, “Why don’t you call Holly’s mother? Holly [Johnson], the singer, never had a job, and this is the first job he had. I spoke to his mother last week. So you call her up and tell her you are banning it.” He said, “I’m not going to call anyone’s mother up, but I am prepared to talk to the press and explain my reasons.” I said, “I could set up a press reception.” He said, “Okay, if you can do that.”

I couldn’t get the phone down quick enough. He stood up in front of 75 people that afternoon and told them the record was all about ejaculation. [As a result,] we couldn’t press enough records. We pressed records in Sweden, in East Germany, everywhere. And it just flew off the shelf. So the record jumped from 65 to 30 then to 6. It was just a success story. You couldn’t write a better script.

We had two other hits: “Two Tribes,” very good. Godley & Creme did a great video of Reagan and Gorbachev fighting in a kind of a ring. And that did very well. And the album still [holds] the UK record for a double-album shipped: we shipped 1.2 million double-albums. The reason we shipped so many, because you wouldn’t want to do it, it kind of clogs the system, is that I didn’t think it was very good. A double-album, it only had a couple of tracks that we’d release as singles, two or three tracks. The rest of it was pretty naff.

So we shipped it because by this time I’d discovered that Island had no money. They had no money at all. They were totally broke. You’re obliged in British law… If a company hasn’t got the wherewithal to carry on, you’re supposed to fold it. Anyway, that became a huge hit. That did a lot for the cash flow.

Legend by Bob Marley. Looking through the sales figures, I couldn’t believe that Bob Marley sold so few records. And I had a theory that the way they marketed him in terms of he was always wearing camouflage, he always looked very military-like. Even when he played football, he seemed to be playing it with camouflage clothing. And I felt that white England, the white world, had not cottoned on to how good Bob Marley was. And so I did some research and found a very nice contemplative picture of him in denim. And we put that together, put it on TV, and really spread the word. It’s done 36 million something, something to date. So that was good.

And then U2 came along. They’d had some success with Unforgettable Fire, but they weren’t platinum yet. I discovered that Island had really not marketed any of their groups the way I thought they should be. Robert Palmer told me he was leaving because he hadn’t had his royalties paid. And Steve Winwood was going to Virgin. U2, there was a query as to where exactly they were in the state of things. It turned out that they had a secret agreement with Blackwell to have 10% of the company, but he had to sell the company within a period for them to not take royalties. It was a whole carry-on.

Meanwhile, he now had half of Stiff, and his people were running the accounts department. The royalty department was also run through Island. And I discovered they weren’t paying. I had signed the Pogues at that time to the new Stiff, and it turned out that Blackwell’s people weren’t paying… they were paying Island’s bills now because they had to, but they weren’t paying Stiff bills because they didn’t have to. And people were complaining to me, and I investigated it. There seemed to be a lot of controversy there. So I got out of there with Stiff, but barely. I loaned Island a million pounds to pay their wages for three months when I was first there. And people say, “Well, why did you do it?” And I thought, “Well, I like a challenge, unfortunately. It’s part of my nature.”

We signed a group called Furniture and we signed the Pogues and they went on, both of them, to do very well. Furniture had a great song called “You Must Be Out of Your Brilliant Mind.” I don’t know if you’ve came across that. So that worked well, but then various people who were bottom feeders, who were owed very little money, got together and brought a big case against the company. They joined into a kind of a financial kind of creditor all by themselves. I was the biggest creditor because I was supporting the company ongoing. But that period had a bad effect. And eventually I sold the company to Trevor Horn’s company’s ZTT and worked for the company through the Pogues’ “Fairy Tale of New York.” And then I thought that’s pretty much it.

I didn’t get on with Trevor’s wife, Jill Sinclair. I thought, “I’m going to breed racehorses.” So I went to Ireland and that’s what I did for the next four years. I came back in to do “greatest hits” packages. I did a Billy Ocean greatest hits. I did various greatest hits. Because I liked the idea of putting things in front of the public – music that they might have missed. So that was great.

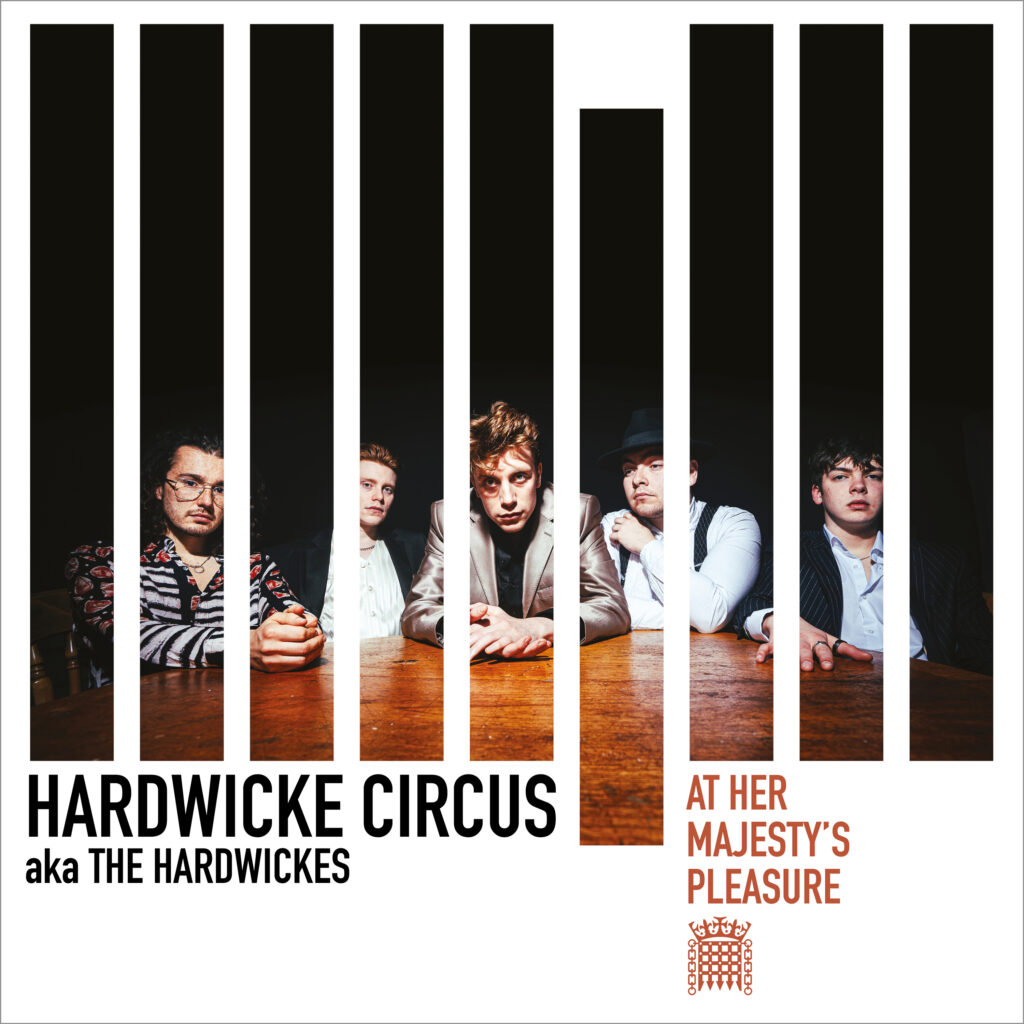

Nowadays, if we jump forward quite a bit, I’m managing a band called Hardwicke Circus, who Paul McCartney has just managed to get onto Glastonbury [the annual festival]. So we’re very happy. But they’re very good. They’re a very young band who were kind of caught in a bubble in their hometown of Carlisle, which is right up on the Scottish border. The music they like is kind of a collection of all the things I’ve been involved in. They seem to have been in a bubble for quite a long period. And we’re making a lot of headway now with music that a lot of people find is familiar, but still very original.

The singer’s voice reminds me of Billy Bragg a lot.

Yeah, yeah. There is a lot of that. That song “A New England” that Kirsty did, that kind of area of music. So it’s keeping one’s hand in, keeping going, with a band that I think can do stuff. But it’s a very changed world now. You and I have been through the ups and downs of it. Streaming is a fact, but it’s not useful. It’s very good for major record companies, who don’t do anything now. They don’t distribute anything. They don’t manufacture anything. And they don’t pay everybody. So they’re having a really good time. And it’s unfortunate because there’s very few ways that one can fight against this. It’s a state of being. But live, and Hardwicke Circus is great live, there’s still those kind of avenues. So it’s exciting.

You produced the live album for them?

The prison album is called At Her Majesty’s Pleasure. Because in a court in England, when you’re sentenced, they say, “And you will get 10 years at Her Majesty’s pleasure.”

I have always had bands play in prisons because I think, “Why shouldn’t music go into prisons?” I thought Johnny Cash’s efforts were phenomenal.

This album was made in several prisons during the pandemic. The band have an opening for somebody to come up and do a song or a rap with them in a song called “When the Chips Are Down.” And they invite a participant. So this guy jumped up and did the most remarkable version of “Born Under a Bad Sign.” He had an incredible Scottish voice, and the audience went completely maniacal. I mean, seriously over the top. And I wondered why that was. Prison officers, everybody was on their feet giving this guy an incredible hand. And the band. It turned out he hadn’t spoken to anybody in that prison for six years. He looked very greasy. He looked like he was homeless in prison. And it turned out for six years he hadn’t spoken. And this was the very first time.

I’m told by the officers in the prison subsequently that it had a great effect on him, that he came out of his shell, that he had been badly bullied, but he had a big personality and become somebody in the prison. I’m fascinated by music and what it can do. It’s done a lot for me. I think it is done a lot for a lot of people. And you don’t hear those stories that often.

You dragged Alan Winstanley out of retirement to produce them?

Yeah. He’s been playing golf in Portugal all this time. I called him up, and he came to see them. He didn’t just take the gig. He came to see them, really liked it, and he signed up for the next one. So we’re working on The Second One, which is the working title for their second album, which Alan will also produce.

Your son Milo is kind of responsible for this chapter in your life?

Yeah. He discovered them, in Camden Town of all places. He heard some music in the pub that he knew didn’t have live music. He’s a photographer, so he went in and took a few pictures. There was this young group playing in the center of the floor, and he made some inquiries. And it turned out they had appealed to the Irish landlord, saying they’d come all the way from Carlisle and blahdy, blahdy, blah, and could they play? And he allowed them because they’d come so far. The Irish have a very sympathetic way with them.

So I went to see them the following night. Milo wanted to manage them, but he wanted my signature on the document to encourage their parents, as they were quite young, to put up with the idea of an English manager. So I became the co-manager. But the plan was he was going to do all the work and I was going to make the odd observation perhaps.

Anyway, his photographic career began to take off and he came and said, “Look, sorry, Dave, would you mind kind of going on with it? Because I’ve got to step out now. I’m going to do this other thing.” So that’s why I’m here. And we get on, and they’ve improved immensely. They’ve done the work. Their writing is now on a serious level. So Paul McCartney giving them a thumbs up, I think will be good for them. Certainly good for me. And it’s the full circle. We’ve been around this block so often, and here we are again.

What happened to the Hope and Anchor tapes?

They’re still kind of in the ozone. Some of them got mixed. Elvis, Declan at the time he played there, I recorded him in the studio. I think we did about 38 songs in about eight hours. And a lot of them he kind of cannibalized; they became his next three or four albums. Great Nick Lowe-influenced songwriter, we all know that. He’s tried everything. Actually, he’s got a remarkable nerve, so he’s tried an awful lot of stuff, some of which I think is good, some of which I think is terrible. And he still comes out the other side shining. So he’s good.

The rest of it was going to be a live album. There was going to be a Live From the Hope and Anchor. And there was a live album, some of which were tapes that I recorded there. But Graham Parker’s career took off very quickly. And that’s kind of the step between the Hope and Anchor and Stiff. It got very exciting very quickly. Into America, Springsteen coming to the shows, not that he was famous at the time. But Steve Popovich, a mate of mine who was a promotion man at CBS, now Sony, he said, “You got to listen to this guy. He’s probably as good as Graham Parker.” I thought, “Oh, yeah.”

Anyway, all those things are worth talking about and worth contemplating the whys and wherefores. What is it they say? “Another hit, another writ,” the writ being a legal case in the UK. So it’s been good.