By Jay Nachman

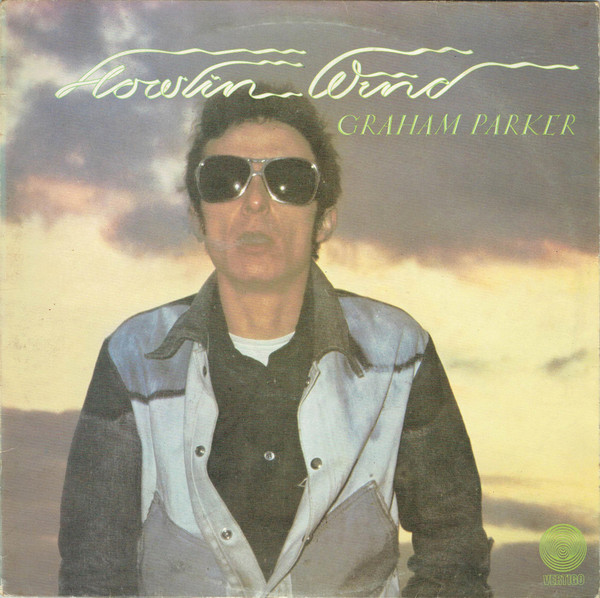

Graham Parker’s debut album, Howlin’ Wind, placed fourth in the 1976 Village Voice Pazz & Jop Critics’ Poll. In second place was his sophomore album, Heat Treatment. Number-one was Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life; Jackson Browne’s The Pretender came in third place.

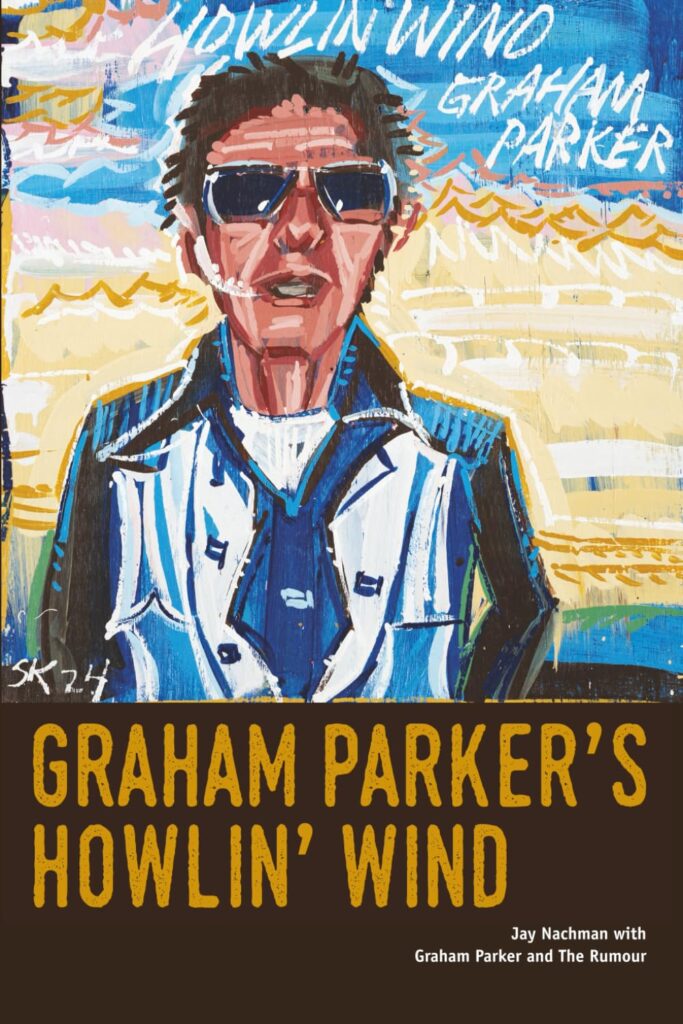

In his new book, Graham Parker’s Howlin’ Wind, author Jay Nachman tells the story of making that acclaimed 1976 album, using interviews with Parker, Nick Lowe, all of the members of the Rumour, manager Dave Robinson and others. It explains why Nigel Williams could claim, in the liner notes to Parker’s 2001 release, That’s When You Know, “Graham Parker and the Rumour had revitalized British music with their debut album . . . at the time, Parker appeared to be the savior of British music.”

In this excerpt, Lowe confidently tries his hand at making an album with Parker and the Rumour, some of whom had no real experience in recording studios.

Up to that point, Nick Lowe had only a few production credits. He had produced the pub rock band Bees Make Honey and his own novelty song “Bay City Rollers We Love You” (as Tartan Horde) in a gambit to get out of his United Artists contract. Nonetheless, Dave Robinson [Graham Parker’s manager and co-founder of Stiff Records] knew that Lowe had it in him to be a producer.

Lowe said, “I wasn’t nervous at all . . . Back in those days, anyone could be a record producer if they said they were one, if they could persuade somebody to go into the studio with them and be directed. I had confidence, and I’d listened to a lot of records, so thought I could do it. And that was all the qualifications I needed for the job. So I was thrilled to be asked.”

Robinson brought Lowe to Newlands [a south London pub that had become the band’s base] to meet Parker and hear his music. Parker took an instant liking to Lowe. But more importantly, Parker said, “There was no doubt to me that if Dave thought he could do it, he could do it.”

“I felt a great sense of relief because I thought the songs were so good,” Lowe said, adding that he had heard “Between You and Me” on Charlie Gillett’s radio show. “I really loved his songs because they had great lyrics, and he put them across really well. But he had a pop sensibility, as well.”

The musicians set up shop in the (sophisticated for its time) 16-track Eden Studios. The moment had come for Parker to make his first album, and he was ready to meet the moment. First, though, he had to retire his reliable red guitar, the one he had purchased in Guernsey, the one he had used to write all his songs. It wasn’t up to professional standards, he was told. So Parker bought a Guild acoustic. “I knew very little about guitars,” he said. “The Rumour approved that somehow or another. Brinsley Schwarz didn’t say you shouldn’t get a Guild.”

With money from his record deal, he also purchased his first good electric guitar, from Lowe. It was a Fender Telecaster, with a neck cribbed from who-knows-what other guitar. Parker paid ₤150. Lowe was happy to be rid of the instrument. “I’ve never been a very good electric guitar player,” he said. “It was sort of depressing, having it around my flat and being unable to play it.”

Now Parker had two guitars with what he called “some credibility.” Lowe said, “I know that he did sound better after he bought my Tele off me. It definitely was a good buy on his behalf.”

Eden was the first proper studio that Parker, bass player Andrew Bodnar and drummer Steve Goulding had recorded in. The studio came with an engineer and had a large room to record in, as well as a spacious control room. It also had a television and a kitchenette. There was beer and pot, too. At times, some of the musicians would be low-key stoned, but they were focused on the music.

“It was really comfortable,” guitarist Martin Belmont said. “I’d made a couple of albums and an EP with Ducks Deluxe. I’d been in the studio a bit. Brinsley and Bob [Rumour keyboardist Bob Andrews] were much more experienced being in recording studios than me, but I was more experienced than Steve and Andrew. You wouldn’t never guess. The bass and drums are fantastic. They’re absolutely a killer rhythm section.”

Lowe agreed, describing Bodnar and Goulding as great players who knew instinctively what to do, which made his job easier. Lowe later used them on other songs he recorded and produced.

Lowe had been paying attention to the marketplace, and his intention was to make Parker’s rootsy music acceptable to the British market without trying to produce a feeble copy of the real thing. He wanted to use the soul stylings that Parker was using to sing on some of his tunes without the songs sounding like a “lame British cover but had that sort of element in it. I wanted it to sound British, not like we were trying to sound American.” But he didn’t quite know how to do that. With hindsight, Lowe said, he would have done different things with the horns, produced them in a more British way. For example, he said, he might have made them less funky, less forceful.

Danny Ellis, who played trombone on Howlin’ Wind, recalled Lowe coming out of the control room and saying to the horn section, “Guys, I don’t want you to sound like session musicians. I want you to loosen up a bit. Play loud and sloppy. You’re too professional.” Said Ellis, “We didn’t know how to do that very well because we were used to being tight. We were all professional musicians.”

It would have been difficult for Lowe to make the horns more British-sounding, Ellis said, because Parker was American-sounding. “He wasn’t your typical British musician. If you listen to a band like Madness or you listen to the Clash, they’re very British.”

Lowe had concerns that there could be awkwardness between himself and his old Brinsley Schwarz bandmates Andrews and Schwarz. But all were willing to quell any tensions and not get caught up in the squabbles that sometimes came with making Brinsley Schwarz records. Lowe also had to guard against Andrews, Belmont, and Schwarz being so familiar with each other’s chops and licks that they would turn to styles that had served them well in their previous groups.

“They knew that I was what was on offer then, and they knew that I was going to do my best,” Lowe said. “It was the first serious record I’d done, and I was going to get paid for it. Not very much, but I was going to get paid for it. So I was determined to do my best. They knew that I wasn’t going to muck them about.” Lowe was paid ₤300 to produce Howlin’ Wind.

For his part, Schwarz was glad to share guitar duties with Belmont because they’d been on the same wavelength from the moment they first began playing together. “Sometimes we just fall about laughing at the way we either both play the same thing or not play anything at all,” he said. “We’ve actually stood there not playing anything at all, waiting for the other one to start.”

Though they were sympatico as musicians, Schwarz said that they had very different styles: “Martin was more into rootsy. I was more band-y in the beginning. I automatically played the lead parts quite a lot. Martin plays what you might call big guitar, and I play more intricate stuff. Martin plays R&B, and I played band. I played more Motown bits.”

Steve Goulding: “On Howlin’ Wind, I just wanted the drums to sound as punchy and lifelike as possible, but I had no idea how to get them sounding like that, apart from tuning them as well as I knew how. They ended up sounding quite different from the way they were recorded on Nick’s first solo album, a lot more normal, understandably I suppose, as you’d want attention to be paid to Graham’s voice and lyrics rather than the groovy-sounding drums. Also, in those days, the engineers were probably a bit more conventional than they were later on. But I was mostly pretty pleased with the way things sounded, with the possible exception of ‘Don’t Ask Me Questions.’ It’s difficult to get a Jamaican recording sound and feel down properly, like Studio 1 or King Tubby. One does the best one can under the circumstances.”

While Lowe was the man in charge, Andrews continued to help with the arrangements, as he had done at Newlands. This was a role he had also assumed with Brinsley Schwarz. “I always had ideas,” he said. “A bottomless well of . . . musical ideas. I’ve got that background, l listen to a record and translate it into notes and sounds.”

Lowe agreed that Andrews was great at that. He called him a fantastic musician and was pleased to have his help. Schwarz said the recording was fairly collaborative. If someone played something and it wasn’t working out, Schwarz said, they were all amenable to suggestions from the other musicians.

[Although Lowe later] developed a reputation for [knocking] out tunes in the studio [earning the nickname “Basher” in the process], his contributions to Howlin’ Wind have at times been undervalued, according to Parker. Lowe was able to work quickly, Parker said, because he was adept at capturing the band’s ability to complement his songs.

“That takes a bit more than just being a drunk and a basher,” Parker said. “He wouldn’t have let anything that wasn’t good enough go through the net. He knew the songs were good. As he was going along, listening, he knew how good they were, and he was not going to be careless. The fact is, he wasn’t going to overproduce it. That’s the thing. He wasn’t going to overdo it. You know, it was going to be rock and roll. It was going to be the band. There was no sloppiness about what he did . . . But the essence of it was, ‘There’s the take. Yeah, boys, that’s fucking great.’ And they’d come into the control room, and we’d all be excited. And say, ‘Okay, yeah, that’s it.’ Or ‘No, we’ve got to do another. Can we do another? One more, maybe.’ Or Brinsley would say, ‘I’ve got to redo my guitar or repair it.’ There were those normal things that you often do. It wasn’t going to take months and months. A band like this is so organic and real, he knew what to do with it.”

Lowe saw his main role as creating a good feeling in the studio. “You can hear if someone’s fed up,” he said, “if someone isn’t on the same page as everybody else. And you can definitely hear it when they are. That’s how I saw my job, really as a sort of cheerleader, you know, and to encourage them to go further . . . to engender an optimistic feeling in the studio.”

That was a successful approach, Belmont said. “We spent a lot of time laughing and joking, which you tend to do with Nick anyway. He’s an easygoing guy, and he’s not one for endless takes until you gain some mistaken degree of perfection.”

“What we recorded was what came out,” Parker said. “We did not have to think twice. There was no wringing of hands or pearl-clutching about whether we should leave songs off or what we would do. We had the material right there. I didn’t have to go back into my more flying-the-freak-flag days. We did not have a great deal of choice, and we didn’t need it.”

After the recording was completed, Parker and Lowe mixed the album together, with band members occasionally popping into the studio to hear tracks and offer suggestions. Parker and Lowe also put together the running order of the songs, without a lot of strategic thinking. The pair listened to the songs on the large studio speakers but did the actual mixing while listening to a small speaker they set on the control board.

“We listened on this very small, single speaker because we wanted to pretend that maybe it would sound like this on radio,” Parker said. “Not an original idea, really, for mixing albums in some way, but it was good to bring it down to earth as opposed to the giant speakers, where it could sound fantastic and you can get misled. It was a great thing. I loved being with Nick, just him and me, into the wee hours, mixing. That was a really good thing about that album. The whole experience was pretty damn good, really.”

Graham Parker’s Howlin’ Wind (c) 2025 Jay Nachman. All rights reserved. Published here by permission of the author.

The book is available in paperback from Amazon.