I love tribute albums. Really. I have an entire CD cabinet of them; the vinyl and cassettes are filed elsewhere. What I have is but a tiny fraction of what’s out there — Wikipedia lists a dozen tributes to Nine Inch Nails alone and 13 for Metallica. That’s fine. I’m a fan, not a fetishist. (And once a contributor: guitarist in the single-session Pippi Eats Cherries, covering “One Day in the Factory” on a 1989 Shonen Knife tribute. Still waiting for my call to do more.)

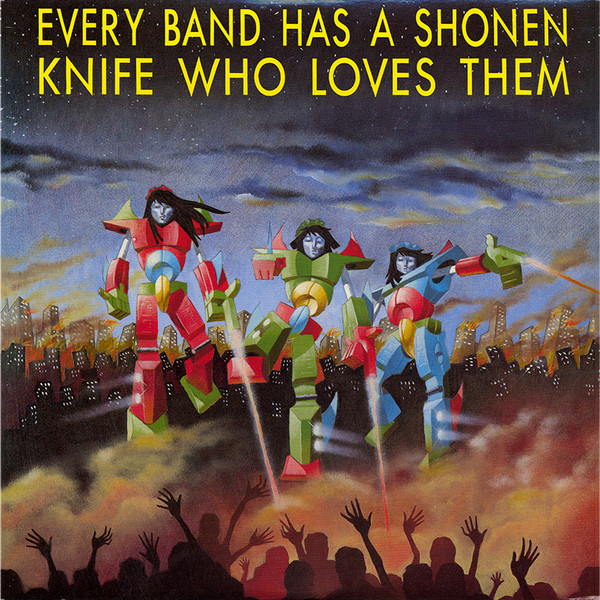

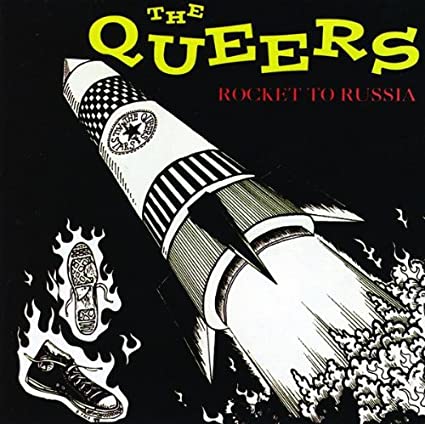

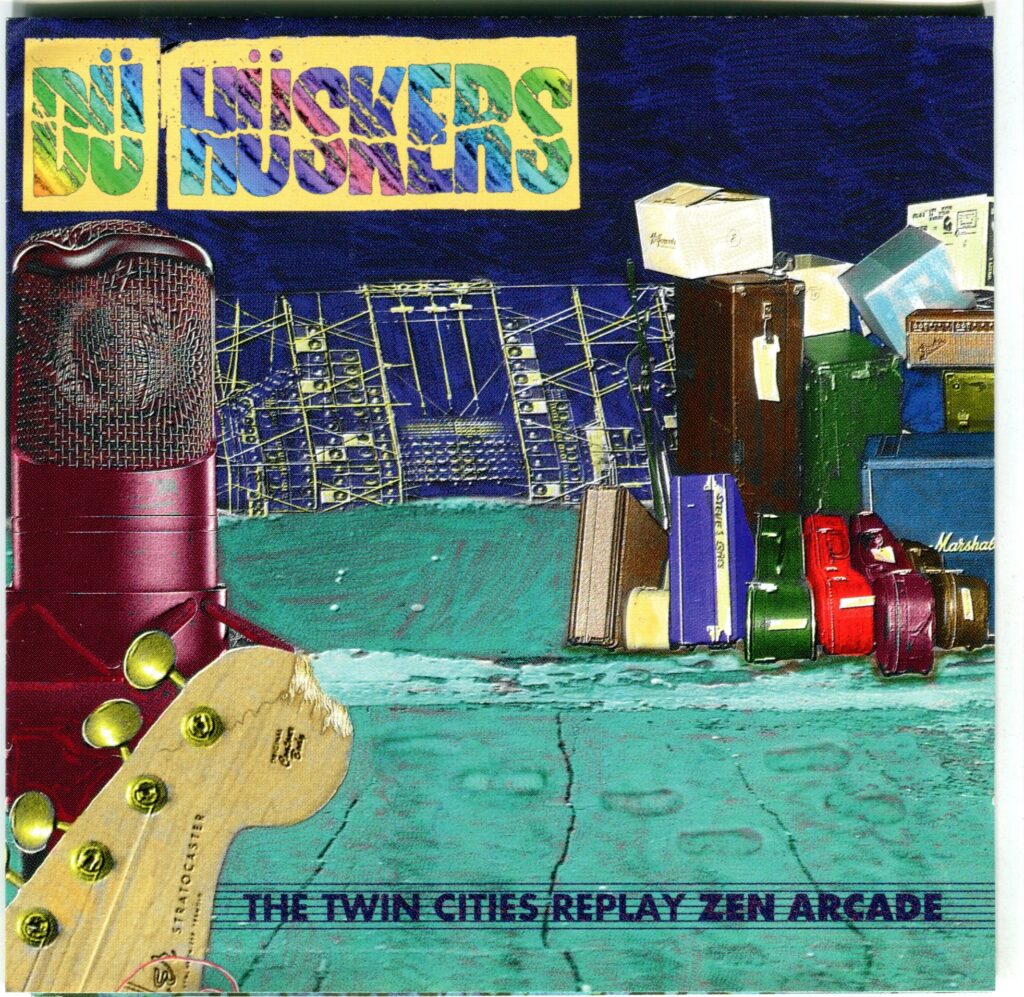

I’ve got albums of one artist mining another’s catalogue (The Byrds Play Dylan, Juliana Hatfield Sings the Police, Eric Clapton’s Mr. Johnson) or replicating a single album (the Queers’ Rocket to Russia, Ryan Adams did Taylor Swift’s 1989, Laibach did Let It Be, Dr. Demento pals Big Daddy did Sgt. Pepper’s (so did Cheap Trick, live). Sometimes it takes a village to remake an album: Badlands: A Tribute to Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, Sgt. Pepper Knew My Father, Dub Side of the Moon, Tapestry Revisited, Dü Hüskers: The Twin Cities Replay Zen Arcade.

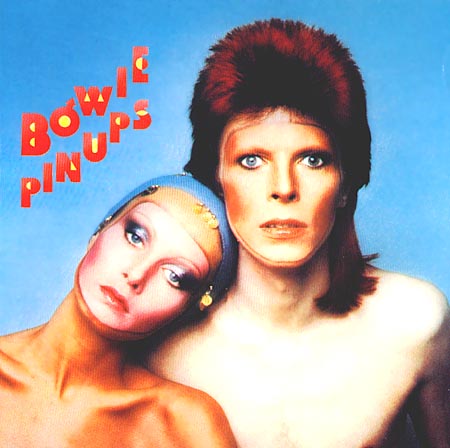

There are remakes of personal favorites (David Bowie’s superlative Pin-Ups, Todd Rundgren’s unfun carbon-copy achievement Faithful, Dexy’s man Kevin Rowland’s bizarrely wonderful My Beauty). Some are devoted to genres (Before You Were Punk: A Punk Rock Tribute to 80’s New Wave, Saturday Morning Cartoons’ Greatest Hits, Big Daddy’s Smashing Songs of Stage & Screen. There are even tributes to record labels: For its 40th anniversary, Elektra turned the spotlight on its own roster and catalogue to produce the two-disc Rubáiyát. Other labels, including Alternative Tentacles (Virus 100), have done similar projects. The Stiff Generation (2002) got a variety of artists (including several who were actually on Stiff) to recall items from its past

There are stylistic sidesteps (Moody Bluegrass, Regatta Mondatta: A Reggae Tribute to the Police,Come Recline With Black Velvet Flag, Sara DeBell’s Grunge Lite (subtitled “A whole big butt-load of easy listening favorites”), 20 Explosive Dynamic Super Smash Hit Explosions) and respectful recreations, like the Rolling Stones’ Blue & Lonesome and Die Toten Hosen’s Learning English, Lesson One, in which the German wags enlisted American and British scene greats to sing on their letter-perfect renditions of punk classics. Pulling further away from the central idea, there’s the Silicon Teens, Moog Cookbook and Peter Gabriel’s Scratch My Back. Inverting the concept completely, A Prehistory of the Bonzos: Songs the Bonzo Dog Band Taught Us digs out original recordings of the bizarre antiquities made “famous” by Vivian and the lads.

Spinning off the venerable tradition of recording duets (which got its modern jumpstart in 1991 with Nat and Natalie Cole and then kicked into high gear with a pair of Sinatra albums cut by artists who never clapped eyes on him; Tony Bennett and others have followed suit) are discs that team stars with guest singers to pay tribute to themselves. Fine on paper, sure, but Ray Davies’ See My Friends and John Fogerty’s Wrote a Song for Everyone demonstrate the clear and present danger of letting friendships and mutual admiration societies guide creative decisions; if you’ve got the original, what benefit does an added voice bring? Suffice to say, artists should never organize their own tributes.

Tuskegee (2011), on which Lionel Richie attempts to follow the long-ago lead of Ray Charles from R&B to country, sends his familiar mush to a modern Nashville processing plant for even more pronounced pop blandness. At least the guests there don’t embarrass themselves. Vocal exertions do Elton John, Steven Tyler, Sheryl Crow and Gary Barlow no favors as William Robinson deftly floats above and around them in Smokey & Friends. (Points to James Taylor and Mary J. Blige for more than respectable showings here.)

Then there are the original efforts that only evoke the honoree; the kind of record that get called “pastiches” in court: the Rutles’ spot-on evocation of Beatles songs which led to a forced division of royalties, Utopia’s similar (but evidently less provocative) Deface the Music. And let’s not start on Liz Phair’s tenuous take on Exile on Main St.

Despite all the options, most tribute albums stick to the basic format: a variety of supposedly keen artists paying recorded homage to a single honoree: I’m Your Fan: The Songs of Leonard Cohen, Stone Free: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix, the execrable but apt Kiss My Ass, the equally inept Killer Queen, Chimes of Freedom, The Last Temptation of Elvis, If I Were a Carpenter, Fortune Cookie Prize (Beat Happening) and thousands more.

I love the idea of tribute albums. I am fascinated by the countless ways a song can be redone. I enjoy the familiar being remade anew. Recognizable bands delight me when they take on a song I like instead of presenting nothing but their own originals. (Despite being proven wrong on a regular basis, I have never gotten over the vague suspicion that all the good songs have been written. I mean, “Waterloo Sunset,” amiright? You could stop there and the world would have gone on.) I love when a simplistic band takes a bash at an intricate piece of music and vice versa. Familiar songs that are inextricably tied up in their established performances — the voice of the singer, the guitar solo, the production quality – can really benefit from an ear-opening change of perspective. So, yes, more please.

If only so many of them weren’t crass, dumb, inappropriate. There is a fine line between tribute and travesty; paying careful, creative homage to a song with resonance and significance is a lot harder than simply stomping the shit out of it. With the trio of options being to (a) ape the original, (b) reinvent it or (c) do what comes naturally in one’s own style, tribute albums can be minefields of poor choices.

Too often, when major labels commission such projects, they corral momentarily popular acts to interpret an important oeuvre, now-forgotten bands who should never been asked. Atlantic’s Encomium to one of its leading cash cows includes tracks by Never the Bride, Helmet, Cracker, Blind Melon and 4 Non Blondes. Led Zeppelin must have felt so special. Ditto Queen, when Hollywood Records corralled Be Your Own Pet, Ingram Hill and Antigone Rising to help show the heroes of Live Aid how great they art. (Reminds me of TV networks filling seats at sporting events with cast members of its shows and making sure the announcers coo when the camera finds them.) When the transient meet the timeless, the result can be shit karaoke, a disrespectful swipe at an artist far more accomplished than those who are supposed to be honoring them. Selecting the right acts (big names or big fans? both?), guiding their choices and then ensuring that what they deliver honors the original rather than insults it is a most difficult undertaking. There are far more self-aggrandizing misses than hits.

Case in point: Working Class Hero: A Tribute to John Lennon, a high-profile charity project to benefit the Humane Society, is pretty much an act of artistic desecration, thuggy hard-rock renditions of Lennon’s solo creations by Red Hot Chili Peppers, Candlebox, Cheap Trick, Sponge, Blues Traveler, Flaming Lips, Collective Soul and others. Other than the avowed Beatlemaniacs of Trick (some of whom were actually brought in to record parts for Double Fantasy that went unused), none of these acts have obvious connection to Lennon or his music. So while Screaming Trees bring appropriate solemnity and resentment to “Working Class Hero,” Toad the Wet Sprocket manages a perfectly respectable “Instant Karma!” and the Minus 5 revs up “Power to the People” (hardly one of Lennon’s great compositions), most of this is inexplicable and bad.

Released a decade later, Instant Karma, a two-disc Amnesty International fundraiser to aid Darfur, is appreciably better (U2, R.E.M., Los Lonely Boys, Christina Aguilera, Snow Patrol) but also, in spots, worse (Lenny Kravitz, Avril Lavigne, Jack Johnson, Matisyahu). Aerosmith’s devotion to the Beatles is well-established (jeez, they were even in the Sgt. Pepper’s movie), but Tyler’s showboating here is grotesque; the restrained performances are the ones that stand out here. (Oddly, of all the bands in the world, Flaming Lips are on both Lennon sets.)

I don’t believe anyone sets out to dump on a song, but errors in judgment down the line make greatness in tributing a rare commodity. A prism can reveal vision or just distort a view. I really wish these projects were approached with a more discerning selection process, assembling musicians of evident relevance who can bring something of value to the effort. The 2007 Joni Mitchell tribute does it right, concentrating on artful female vocalists who surely appreciate the greatness of her work. You know that none of these superlative singers – a cast that includes Bjork, Prince, Caetono Veloso, Cassandra Wilson, Annie Lennox, Sarah McLachlan, k.d. lang and Elvis Costello — took their assignments lightly, and the results are superb.

The late Hal Willner is regarded by many as a genius in this realm (for his tribute albums to Kurt Weill and Leonard Cohen as well as several jazz greats and others), but AngelHeaded Hipster, the T. Rex tribute album he produced before his COVID-19 death in early April and which will be released in September, looks like a mixed bag. I don’t mean that in a good way. (Anything with Perry Farrell and Father John Misty on it is already suspect in my book, and this list of artists suggests a fair-to-middling risk of preciousness, which would be like carrying coals to Newcastle. The near-absence of contemporaries is also worrisome. From my snobbish perch, I’d be curious to know how highly artists like Kesha and Devendra Banhart prized the music of T. Rex before getting this call.)

- Children of the Revolution – Kesha

- Cosmic Dancer – Nick Cave

- Jeepster – Joan Jett

- Scenescof – Devendra Banhart

- Life’s a Gas – Lucinda Williams

- Solid Gold Easy Action – Peaches

- Dawn Storm – BØRNS

- Hippy Gumbo – Beth Orton

- I Love to Boogie – King Khan

- Beltane Walk – Gaby Moreno

- Bang a Gong (Get It On) – U2 featuring Elton John

- Diamond Meadows – John Cameron Mitchell

- Ballrooms of Mars – Emily Haines

- Main Man – Father John Misty

- Rock On – Perry Farrell

- The Street and Babe Shadow – Elysian Fields

- The Leopards – Gavin Friday

- Metal Guru – Nena

- Teenage Dream – Marc Almond

- Organ Blues – Helga Davis

- Planet Queen – Todd Rundgren

- Great Horse – Jessie Harris

- Mambo Sun – Sean Lennon and Charlotte Kemp Muhl

- Pilgrim’s Tale – Victoria Williams with Julian Lennon

- Bang a Gong (Get It On) Reprise – David Johansen

- She Was Born to Be My Unicorn / Ride a White Swan – Maria McKee

Bolan has never been given his due in one-hit-wonder America so this is something of a consequential gesture and likely to introduce many to some of the songs that made him a superstar in the Britain in the early ‘70s. Sure, a lot of these folks are likely to have turned in recordings worth hearing, but Bolan’s songs are such distinctive creations that performers of such forceful style are at risk of, intentionally or not, pulling off their wings or, at the very least, overpowering them. And, truth be told, Bolan was a performer first and foremost; his songs are wonderful but they were part of him and don’t really live by themselves in the world the way so many other artists’ do. I don’t feel any great curiosity about hearing anyone redo them any more so than I want to hear Bill Monroe reinterpreted. Or Slade. (Turns out there have already been at least a half-dozen such undertakings.) I’ve heard what Nick Cave did, and his decision to melt Bolan down to a dirge favors the singer not the song.

The first tribute album to bowl me over, to make me approach and appreciate a set of songs anew, was Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye, a 1990 convocation of (mostly) Warner Bros. artists, a bunch of them Texans (ZZ Top, Butthole Surfers, Doug Sahm) but also R.E.M., John Wesley Harding, Julian Cope, T Bone Burnett, Jesus & Mary Chain) assembled to get Roky Erickson’s wonderfully nutty songs a mainstream hearing. A few years later, another Texas eccentric was the beneficiary of a superior tribute project: Dead Dog’s Eyeball, in which K(athy) McCarty applied her winning musicality to some of fellow Texan Daniel Johnston’s most endearing tunes. As he had recorded most of them alone with rudimentary instrumental accompaniment on a boom box, her loving interpretations fleshed out his naïve art with delightful results.

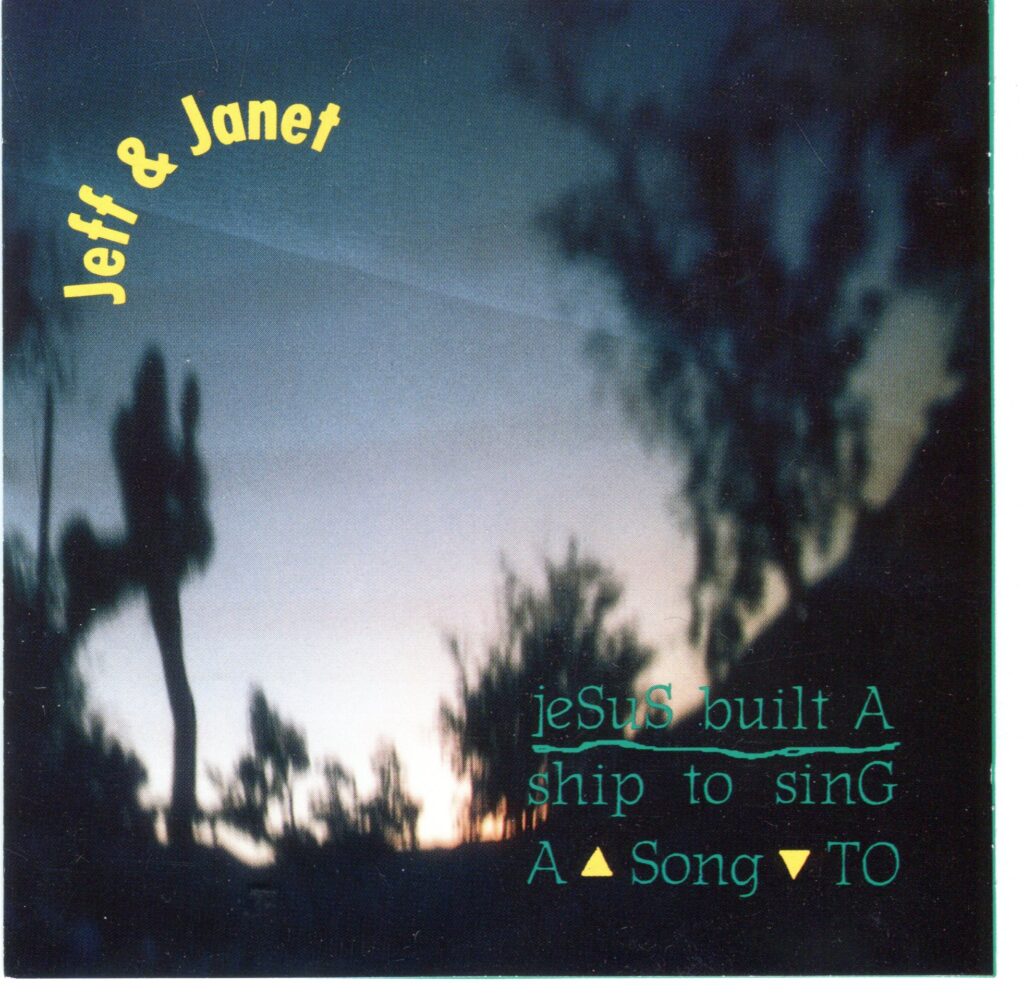

Another one I love from that same year (1994) is Jesus Built a Ship to Sing a Song To, a frisky-to-maudlin CD of (very loosely defined) Gram Parsons songs done by Jeff & Janet (Jeff Lescher of Green and Janet Beveridge Bean of Eleventh Dream Day and Freakwater). I don’t care much for Parsons (don’t @ me, I never thought he was the great avatar of country rock), but this one did as much as any other release to make me grudgingly appreciate his material.

In the ‘90s, a pair of fundraisers (Sweet Relief: A Benefit for Victoria Williams and Sweet Relief II: Gravity of the Situation (The Songs of Vic Chesnutt)) set the template for sensitive, meaningful interpretations that paid respect to their songs and helped the artists both financially and culturally. The Red Hot + Blue series to benefit an AIDS awareness charity also held to a high standard. In the ‘80s, Alan Duffy’s Manchester indie, Imaginary Records, put the tribute spotlight on Barrett, Beefheart, Nick Drake, the Bonzo Dog Band; if the bands involved were all over the place and the results likewise uneven, the intent was unimpeachable. And who else would produce a tribute to a single year? Through the Looking Glass: 1967 hits all the high spots, American and British, with sterling versions by the Shamen, Death of Samantha, the Bevis Frond and Mark Burgess.

Back to the future. I am delighted to report that Saving for a Custom Van (Father/Daughter Records), the 31-track Adam Schlesinger tribute that came out in early June, gets it all right, with due respect and understanding for the artist and the music. His Covid-19 death on April 1st pulled the curtain back on a vast songwriting catalogue; those who only knew him as half the creative team in Fountains of Wayne (or, god forbid, just as the “Stacy’s Mom” dude) encountered a much wider panorama that includes the bands Ivy and Tinted Windows, commissioned movie music (for Words and Music, That Thing You Do, Josie and the Pussycats) and television. Over the course of four seasons, My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend tapped him like a musical comedy fountain; he had a hand in 157 (!) songs song star Rachel Bloom sang and mugged and danced to. He even gifted the otherwise undistinguished Click Five a couple of tunes. And won a Grammy, three Emmys and an Oscar nomination for his troubles.

Schlesinger’s FoW partnership with Chris Collingwood produced a heap of wonderful, distinctively wry and mocking pop songs that showed off their pop culture bona fides – and laughed at themselves with sardonic wit. They wore suburbia like a badge of honor while giving the culture a merciless ribbing, a relocated Richard Linklater film in song. A lot of their lyrics concerned office work, drinking (a Chris specialty, and none of those songs are represented here) and life’s small failures and frustrations. Listening to Fountains of Wayne you heard a self-amused nerd saying things out loud that should probably have been kept to himself.

It was never clear who wrote what, although I did get this breakdown of the first album during a 1996 interview with them:

- Radiation Vibe – Chris

- Sink to the Bottom – Adam

- Joe Rey – Chris

- She’s Got a Problem – Adam, except it was Chris’s title

- Survival Car – Chris

- Barbara H. – Chris

- Sick Day – Adam, but Chris finished the second verse

- I’ve Got a Flair – joint

- Leave the Biker – Chris

- You Curse at Girls – together

- Please Don’t Rock Me Tonight – Chris

- Everything’s Ruined – Adam

The tracks here glow with admiration, and the performances are, for the most part, lovely, fun and complementary to the originals. The quality of the songs undoubtedly has a lot to do with the quality of the tribute; do right by them and you’re home free.

Schlesinger was never a lead singer, so his creations offer a blank slate for new vocal approaches; they are, as Collingwood wrote in “Red Dragon Tattoo,” “fit to be dyed.” The instinct here is to take it easy, leaving air in gentle arrangements and putting the words and melodies front and center rather than bury them in performance. (One wonderful exception is the effervescently pepped-up “Valley Winter Song” by the Brooklyn band Field Mouse — not Field Mice, although their ideas are not so different. I’m surprised to see the number here; it was one of Chris’s.)

Suzy Shinn and Charlie Brand float “All Kindsa Time” on a shimmering soap balloon that turns a lovely song gorgeous. Ethan Eubanks unwinds “Troubled Times” almost to the point to enervation; Vivian Girls drummer Ali Koehler follows with an equally low-wattage “Hackensack” that consists of her voice, delicate drumming and what sounds like a chord organ. I can’t discern why, but the fact that many of the vocalists are female works brilliantly to the songs’ advantage, leavening the polite pop-rock arrangements with added air and allure.

I don’t know most of the names on Saving for a Custom Van, but comedian Sarah Silverman (who sings about as well as she acts, which is to say not badly) and Ben Lee stand in for Drew Barrymore and Hugh Grant on “Way Back Into Love,” an effectively straight-faced love song written for a romcom about (natch) songwriting. Tanya Donelly and Gail Greenwood of Belly take on “Undertow,” one of five Ivy songs included. (Ted Leo, FoW guitarist Jody Porter, HUNNY and Pottymouth do the others.) Bloom does “Stacy’s Mom,” teasing the faux sincerity of this archly sarcastic swipe at pop convention with theatrical exaggeration. Kay Hanley of Letters to Cleo supplies a cool new wavey interpretation of “Radiation Vibe,” and Nada Surf gives a delicately pretty reading to “Sick Day.” Off Book and the Family Band supercharge Josie and the Pussycats’ “Come On” (which credits Babyface, Jane Wiedlin, Kay Hanley, Jason Falkner and several others as co-writers – what, did they each write a line?) as a giddy Toni Basil romp.

It’s rare that songwriters are anthologized apart from their recorded work; it is one of the less obvious qualities of this album that it detaches Schlesinger’s myriad and diverse creations from their original environments, shorn of familiar singers and production decisions and given respectful consideration by real admirers. Fountains of Wayne had two superlative songwriters with individual styles and interests; it would not be possible to showcase either one independently solely from its archive of recordings. Solo albums sometimes serve that purpose, but they offer too much temptation for revisionism. Perhaps other great creative partnerships – you know the ones I mean, hidden behind legally binding communal brands – could be dissected in similar fashion, with tribute albums to the creations of each.

Till then, I’ll keep searching for the diamonds hidden in the mountains of mud and hope no one else has to die to get a tribute worthy of them.