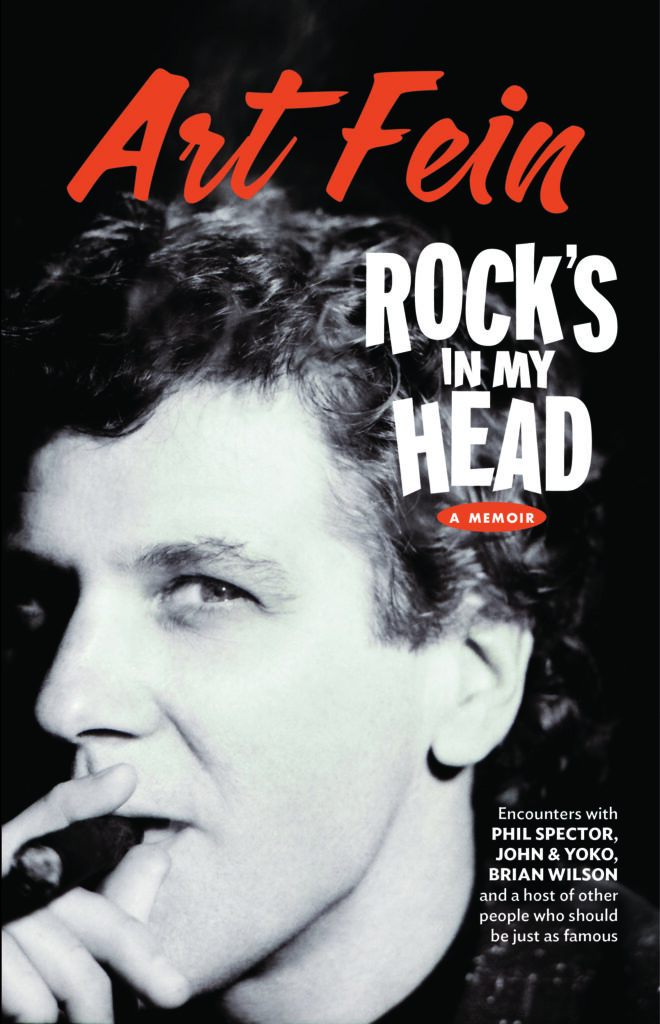

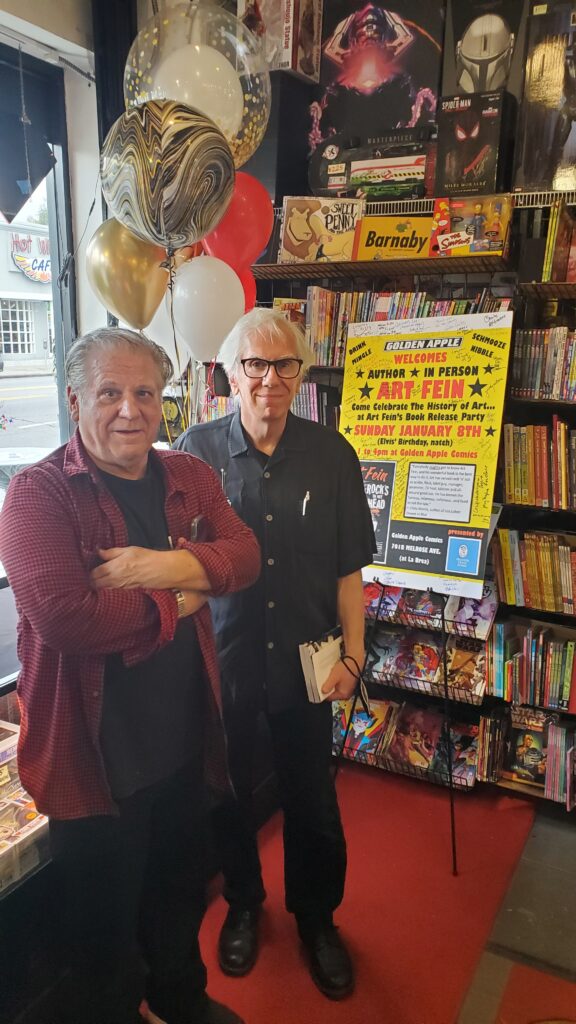

In 2022, Trouser Press Books published Rock’s in My Head, a memoir by the fabled LA scenester Art Fein, based on 10,000 pages of journals he had kept. Art died July 30, following surgery for a broken hip. He was 79.

- Journalist: onetime music editor of Variety, contributor to the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Rolling Stone, Billboardand many other publications.

- Band manager: Blasters, Cramps

- TV host: Art Fein’s Poker Party, a talk-and-live-music public access cable show that ran for 24 years. Guests included Brian Wilson, Dwight Yoakam, Dion, Alison Krauss, Ruth Brown, Jackie DeShannon, Dr. Demento, and loads more. Watch here: https://www.youtube.com/c/sofeinvideo

- Record company staffer: Capitol, Elektra, Casablanca

- Music Consultant, TV and film: Roadhouse 66, Tour of Duty

- Album Producer: L.A. Rockabilly

- Author: The L.A. Musical History Tour, Rock’s in My Head

- Blogger: Another Fein Mess (archived at www.sofein.com)

- Add to that: event promoter, photographer, record collector, and rock & roll historian.

This chapter, which concerns Art’s long, weird friendship with Phil Spector, is titled Re-Phil.

Late January 1988: Just back from Spector’s. I haven’t been to see him in over a year. I like the idea of going there, but I am not thrilled to the bone anymore. Maybe also because there is no musicality attached to it this time; I’m invited up only “to watch the fights.”

The party was at Phil’s enormous new house in Pasadena, a sister to the Beverly Hills showplace, both once owned by Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth heiress. The new mansion was as lordly as the last. “Tom Wolfe was here last week,” Phil said. “He says he loves to visit me because it’s like visiting Versailles. It makes him feel like planning a war.” The room was vast, with large black and white tiles on the floor and a coffered ceiling. A white piano decorated with twin brass falcon heads doubled as a cassette player. On the walls were tapestries, a seeming El Greco, and shields. Two suits of armor stood guard. Near the walk-in fireplace topped by a coat of arms, twin white couches faced each other over an enormous chessboard with extruded-something pieces.

Phil had gathered one of his lawyers; three guys around my age; two women, his friend Jan and employee Devra; and Larry Levine, the fiftyish guy who’d engineered all of Spector’s hits recorded at L.A.’s Gold Star Studios. I was pleased to have been included. We watched a couple of prizefights on satellite TV and chatted sporadically.

I told Phil he looked swell, and he said that was strange because he’s diabetic and can’t eat anything. He was thin, but his complexion looked good. Maybe it was makeup. His wig was very convincing,medium on top and long in the back. We were dressed alike: I wore a black slipover shirt, sport coat, jeans with an orange belt and orange cowboy boots; Phil wore a black collarless shirt, sport coat, jeans with an orange belt, and platform shoes.

I immediately liked easygoing Larry. He mentioned that the Valley newspaper’s TV guide was superior to the one in the L.A. Times. When I asked him why, he laid it out: They had full-page graphs for every day and numerical cable equivalents for initialed channels like A&E. The answer didn’t matter; what intrigued me was the specificity. He spent time thinking about trivial things, as I do. I hoped I’d get a chance to ask him about what it was like working at Gold Star with Phil and his favorite musicians, the gang that became known as the Wrecking Crew. That would come later.

After the boxing matches, dinner was served, hot dogs with potato and macaroni salads. Around 9:00 p.m., several people departed, leaving Phil, me, his lawyer friend, his bodyguard Jay, and Jan. The lawyer asked Phil when he was going to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The 1988 inductees, only the third group, had just been announced. Phil was off and running. Rant highlights: “They ask me all the time. They say, ‘Tell us when you want to be inducted.’ But they want me to play their game.” Their game was having him go on TV and present awards and be friendly. “Why do it? Who wants their award? Who are they to give awards? They give them to the wrong people. The Beach Boys only made two decent records. ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ was good, only it was copied from me. And ‘Good Vibrations’ was an idea, not a record. Certainly not rock & roll…Bob Dylan isn’t rock & roll. The Beatles? No British band should be let in ’til the year 2000—they killed rock & roll… Dick Clark should be the first one in, not Carl Perkins, who had one hit. Maybe you think Dick Clark is a schmuck, that he stepped into rock & roll accidentally, that he only used it to advance himself, but not having Dick Clark in would be like having a Sidekicks Hall of Fame and leaving out Ed McMahon!”

The Chordettes’ “Born to Be With You” was on the jukebox. “Listen to the guitar,” Phil said. “Da-dot-a-lottle-lottle. I stole that for ‘Corinna Corinna’.” Then Jack Scott’s “My True Love” played. “Listen to the ba-dah-dah-dah. That’s where I stole the intro to ‘To Know Him Is to Love Him’.”

Later, Phil argued with Jay the bodyguard, a tall, withdrawn, 30ish guy with long hair and a beard. Phil insisted that Francis Ford Coppola is a great director and Martin Scorsese is nothing. Jay supported Scorsese. A telling snippet: “What’s Coppola done since The Godfather?” Jay said.

“It doesn’t matter!” Phil declared. “When a man’s done something brilliant, you don’t point to his lesser works as if they negate it.” I thought that Phil was saying he is a genius based on what he did 20 and 25 years ago; it stands.

The next day Phil’s assistant called and said Phil wanted me to organize a gathering of guys and one woman (rock journalist and radio host Kristine McKenna) he’d seen on my TV show. That get-together happened a couple of weeks later. I invited three of the Pumping Piano gang—Gene Sculatti, Bob Merlis, and Dick Blackburn—along with Hudson Marquez, an ebullient artist, video documentary pioneer, and former tour manager of Canned Heat. Kristine couldn’t make it; she’d appear at a future party, one of many I’d assemble at Phil’s over the next two years.

I got there first. Phil bopped down wearing a pink shirt, gray pleated pants and black suspenders. He said he was copying a guy on the TV news show West 57th. He started telling me stories about Cameo-Parkway, the Philadelphia label of Chubby Checker, and I was wishing he would save it for the rest of the guys. When they arrived, Phil said hello to Merlis, whom he knew, then called Gene by his name without being introduced; Phil had seen him on the TV show. Gene was ashen with pleasure. We sat down, and Phil clammed up. He was ill at ease with the newcomers.

I kept asking him questions and his answers were cautious and laconic. The guys were loquacious. Phil said, aside, “What am I doing here? These people want to talk to each other.” But ultimately the barriers broke. Phil relaxed and held forth like Phil:

“George Harrison is back. So what? He hates me. I helped sue him for the ‘My Sweet Lord’ case. He didn’t know he was using ‘He’s So Fine,’ but he was told immediately afterwards that it was similar and he didn’t credit it. So? Which one is he, the third Beatle, the fourth one? He never wrote any songs. John used to keep the good ones away from him and Ringo. Ringo—he’d want to sing their songs and they’d cringe. ‘Oh, we gave him the one about the fishies,’ John told me. ‘These are valuable copyrights, y’know. Can’t have him ruinin’ em.’”

The talk was lively before and after a hot dog break. We mentioned we’d been to lunch with Humble Harv Miller, the ex-L.A. DJ who shot his wife in 1971—accidentally he said, in a struggle to wrest a gun from her—and did time. Phil kept coming back to the fact that Harvey didn’t kill her, he executed her, which was alright because she was fucking a promotion man. This opinion must have lain festering in his craw for 15 years waiting for someone to reopen it.

February 1988 Phil asked several times what we were all doing there. I’ll tell ya. Phil is a lonely millionaire who wants to be the life of the party. This party he organized based on my TV show, which he enjoys. (He even mentioned watching some of them in Europe, on tapes he brought along.) He was nervous having a drawing room full of “strangers,” so he asked Devra, his employee, to sit in, and then Jan, his friend, to participate.

The party ended at 1:45 a.m. when Hudson, claiming fatigue from getting up at 4 a.m., yawned and begged to go, and then Merlis followed suit. That would have left me, but I wanted to go, too, because I was slightly ill from eating hot dogs, pretzels, jelly beans, M&Ms, sauerkraut, and cake. We all left in a wedge, and the suddenness of it threw Phil. He switched on the jukebox—until then there was only classical music piped in—as if to keep us there in party mode, but our exit in unison was unstoppable. He shook hands graciously and we thanked him profusely for having us. As our various cars fired up and headlights popped on, I saw him alone in his foyer watching us go.

We all enjoyed him. I know he enjoyed us. He had an audience, and a sharp one. How often did he find a group of okay guys who know what he’s talking about? We dropped him thank-you notes.

February 1988 The visit made Merlis a celebrity at work. Lenny [Waronker], the prez [of Warner Bros. Records], was flabbergasted. The visit might have been an inadvertent audition. Merlis told Lenny that Phil is witty and coherent and generous. Maybe WB would do another Spector project now.

(c) 2022 Art Fein

Rock’s in My Head is available from Trouser Press Books as well as Amazon, Bookshop.org and most eBook platforms.