By Tony Alterman

The Bad Name Bug

It started back in days of acid rock: Jefferson Airplane, Pink Floyd, Moby Grape, Strawberry Alarm Clock, Electric Prunes — word salad band names, random association monikers. Names so absurd they became statements in themselves: a sign that rock and roll was not going to play by institutional rules of meaning any more than a new generation would abide by conventions of dress, habitation, sex or drug use. Screw meaningful names (the Beach Boys), clever word play (the Beatles) and star trips (the Dave Clark Five) — here’s Bubble Puppy!

If you dug a little, though, some of the names had stories. There’s one linking Blind Lemon Jefferson to the Airplane through the medium of Jorma Kaukonen’s nickname. “Bubble Puppy” is allegedly the corrupted name of a game in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Sopwith Camel was a World War I airplane. Still, you could be forgiven for thinking the band names were picked by throwing darts at a newspaper and for convicting their bearers of linguistic nihilism.

History, as they say, repeats itself. For some reason, Australia has “got bit by the bad-band-name bug,” as one reviewer put it with regard to the Perth band Psychedelic Porn Crumpets. Paste‘s 2019 piece on “20 Rising Australian Bands You Need to Know” also tweaked them for advertising their genre so plainly, but that fraught critique could topple a lot of others. Names can be misleading, too: the Psychedelic Furs were not particularly psychedelic, Daft Punk isn’t a punk band and Grand Funk Railroad had nothing to do with funk.

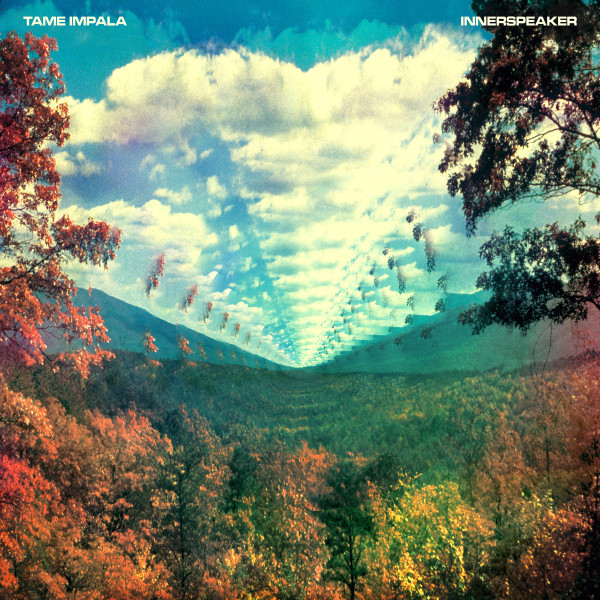

Perhaps it is no surprise that an English-speaking country that boasts billabongs, swagmen and drongos should also sport bands with incomprehensible names. The difference, though, is that some current bands have names that are likely to be bizarre even to native Australians. Consider, by contrast, the stage name of Australian alt-rock luminary Kevin Parker: Tame Impala falls neatly within the nomenclature of a zoological era that saw a herd of bands like Animal Collective, Grizzly Bear, Fleet Foxes, Cage the Elephant, Modest Mouse, Deerhoof and Gorillaz, to name just a few. If I were trying to attract attention after 2010, the last thing I’d do is invent another zoomorphic band name. Some colleagues of Parker’s, also from Perth and of similar neo-psychedelic inclinations, go by the minimalist name Pond (previously used by a ’90s Portland band). Aside from being across a large one from the rest of the English-speaking world, the name may be subtly evoking the unique Aussie vocabulary: a billabong is a pond left by a dried-up river.

Cover art is often a more accurate indicator of how a band wants to position itself, and while the Porn Crumpets’ name already points in that direction, their sleeves underscore their music’s relationship to hallucinogens. Stepping boldly into a long line of bands who have looked to acid rock for inspiration, they are described by Wikipedia as “a psychedelic rock band” as well as “progressive” and “garage” (presumably not in the same song) and “alternative.” PPC have a U.S. tour booked for October.

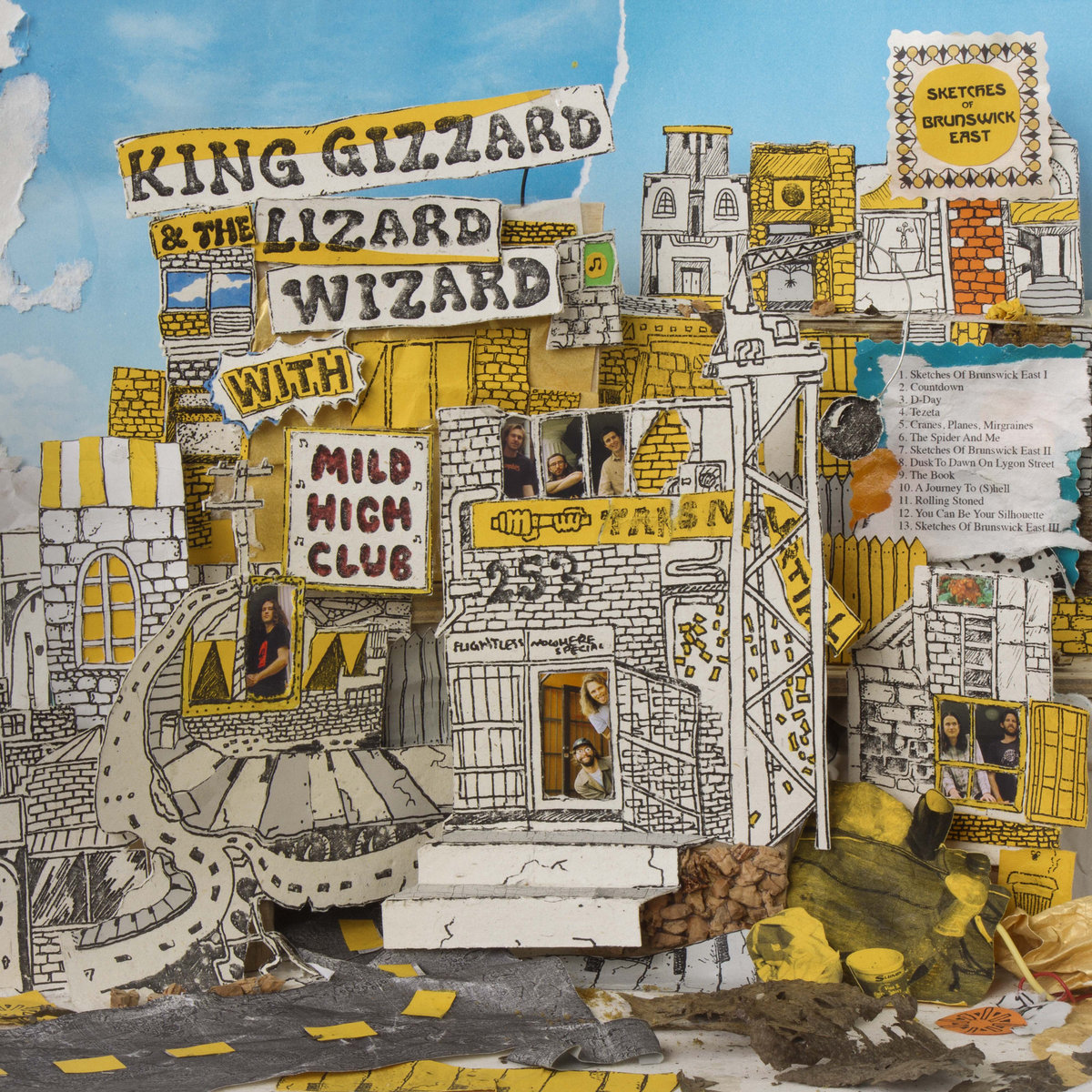

A short sail across the South Ocean from Perth to Melbourne finds the seas of language getting even choppier. King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard is a band whose chameleonic musical style seems designed to fit its designated species. The name is attributed to a compromise between a Jim Morrison reference (Lizard King, his nickname) and the proposed “Gizzard Gizzard.” “Psychedelic” figures in three of the seven genres assigned to them on Wikipedia (“acid rock” makes four). “Heavy metal” is there too, not without cause: among their cornucopia of albums, a few are prog-metal. They also have U.S. touring on the schedule, with sold-out large-venue shows this month (May) and a return leg in October. Given their prodigious album production (an average of two a year, including five in 2017 alone), it’s hard to imagine how they have time to travel.

Another Melbourne outfit with a foothold in America is Hiatus Kaiyote, presumably pronounced as it looks; they sold out Brooklyn Steel on March 11th, just a few days before their better-known neo-psychedelic compatriot Tame Impala performed two nights at New York’s Barclay Center, and are scheduled to come back Stateside in August. They could be called a neo-soul band without much injustice to that genre, but their music, heavily influenced by jazz fusion, tends to wrap their songs in layers of synthesized sound, thus earning them a “future soul” label — one of Wikipedia’s finer category coinages. (Janelle Monáe, Laura Mvula, Thundercat and others have also been combining electronics, African drumming, film music, etc. with older R&B styles in an effort to transcend familiar formulae.) Hiatus Kaiyote’s music is critically dependent on the lead vocals of Nai Palm, the stage name of Naomi Saalfield. (She apparently began using the name after a stint as a fire performer, but the play on words is a bit unsettling in light of the horrifying images of napalm’s use during the Vietnam War.)

Tropical Fuck Storm’s name is apparently intended to deflect any efforts at coverage in the New York Times. (If the paper refuses to quote Ukrainian soldiers telling a Russian warship to “go fuck yourself” why would they lower their standards for a Melbourne rock band?) “They have the best band name,” opines Vice, in a contrarian mode. (An argument could be raised that the name has a certain internal logic, tropical storms being what they are.) Attempts to categorize TFS’s unique style (Wikipedia, again) include “art punk, noise rock and experimental rock…psychedelic rock” as well as various strains of blues rock. They got together in 2017, but founders Gareth Liddiard and Fiona Kitschin began in in the ‘90s in the older and more decorated Drones (unrelated to the class of ’77 Manchester punk outfit).

Last but not least in the naming contest is another Melbourne outfit, Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever. Their latest album reduces the surname to “CF,” and there’s a story about that. According to an interview, “…their name ballooned from Rolling Blackouts to Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever to dodge the online threats of a tiny American band of the same name. [Author’s note: please define “tiny” in relation to rock bands?] Singer-guitarist Tom Russo: “We just decided to add some more words; make it sound as absurd and melodramatic as possible. We have the longest, most unwieldy band name you’ve ever heard.” (Clearly they didn’t discuss this claim with King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.)

Musically, the band makes no secret of their admiration for the Go-Betweens, an Australian group that managed an international reputation, as well as the Feelies and 1980s folk-rockers the Triffids. They are generally said to be doing “jangle pop” or “post-punk.” With a new album, Endless Rooms, out now on Sub Pop, RBCF are due to make landfall in the U.S. in time for Lollapalooza in Chicago at the end of July with dates throughout August.

Before leaving Shakespearean scholars to gauge what’s in a name, consider this: My own band, having managed to book an off-night gig at CBGB in 1980, approached the venerable Hilly Kristal for feedback after the show, and his entire commentary was: “The Vegetables? Pretty commercial name. Could be more commercial. Yeah, we can book you again.” Nothing can be taken for granted in show business; certainly not a name.

Neo-Psychedelia in Perspective

Pink Floyd, Yes, the Moody Blues and others who would come to be the icons of prog rock cut their musical teeth in the psychedelic era, and probably saw themselves at first as carrying on that tradition rather than inventing a new one. As Mellotrons and then early synthesizers replaced organs (and theremins), their compositions became longer and vocal styles changed. But much of what acid rock was about remained — the hazy, droney, consciousness-impacting influence of psychedelic drugs, the search for new sounds, the concept album, the lyrical and artistic challenge to institutional norms. In a sense, progressive rock became the first neo-psychedelia, recognizably different but having a kind of mantle of authority as groups transitioned from one form to the other. (For more on this, from a British perspective, see “The Birth of Progressive Rock,” the first chapter of Edward Macan’s Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture, Oxford University Press, 1997.)

By the mid-1970s, Queen, Klaatu, 10cc and others were creating tracks or entire albums that directly evoked various 1960s acid-rock styles, even though rock music had already moved in many other directions. The first Klaatu album (3:47 E.S.T., 1976) was widely (but falsely) rumored to be a clandestine Beatles reunion recording; its space-rock themes seemed like a natural extension of the Fab Four’s psychedelic period. But in spite of their proximity to the acid rock era, it was already clear that these groups were imitating and celebrating acid rock, not continuing the thing itself. In fact, an odd and portentous phenomenon was unfolding: the closer they came to sounding like the original, the more they appeared to be doing tongue-in-cheek imitations. From a historical point of view, it should have been clear at that point that a revival of acid rock, and all that was deemed lost as the decade ended and new styles emerged, was not even conceptually possible.

The “neo” prefix was first officially pinned to psychedelia in the early 1980s. New wave bands with only halfhearted allegiance to the anger and rootsy simplicity of punk rock dropped the downstrums and disaffected screams to re-examine the history of rock leading up to punk, including acid rock. Post-punk bands like The Teardrop Explodes and Echo and the Bunnymen were described as “neo-psychedelic,” followed in short order by the Paisley Underground in LA, which bubbled up the Bangles, Dream Syndicate, Rain Parade and the Three O’Clock. The 1981 album Wilder by The Teardrop Explodes manages to summon the ghost of the 1960s with some consistency. In name, at least, the Psychedelic Furs were influenced by an admiration for the acid rock era, and the flowing harmonies in “The Ghost in You” evoke the strong vocal harmonies from some proponents of acid rock. While the B-52’s’ “Rock Lobster” conjures up California surf music with a garage band touch, “Love Shack” might have fared well as an acid-pop entry on 1960s AM radio.

Still, there is very little in either British or American post-punk likely to convince a savvy listeners it might actually have been created in Haight-Ashbury, Laurel Canyon, Liverpool or London in the late 1960s. The Dream Syndicate and the Three O’Clock mostly sound like 1980s rock with little to remind one of the Monterey Pop or Woodstock festivals. The Bangles, in spite of their guitar sound and tight harmonies, were quickly revealed to have more in common with their young contemporaries than with the Byrds or the Mamas and the Papas. There is no denying the influence of acid rock on Echo and the Bunnymen’s “Do It Clean” and other tracks that show a similar spirit of experimentation, but they are as unmistakably post-punk as the Furs or Siouxsie. All these bands are very much of their time, inspired by what they heard in earlier recordings.

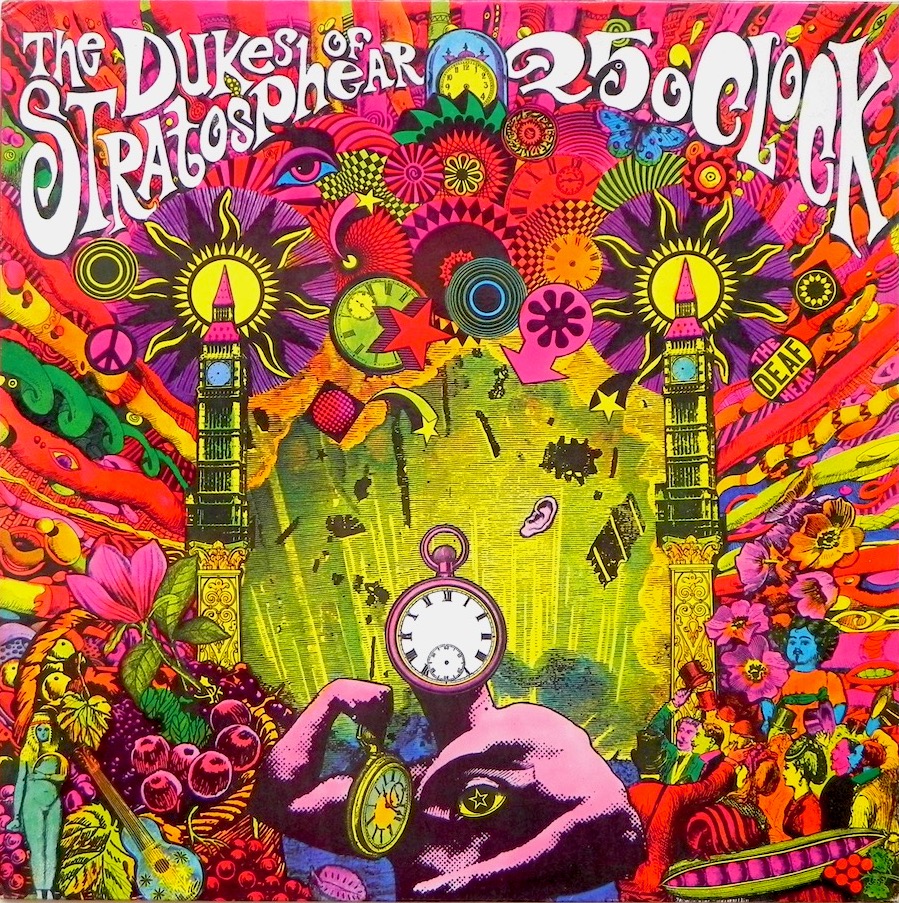

Neo-psychedelia has since become more rarefied. In the mid-’80s, XTC masqueraded as the Dukes of Stratosphear, a detour that, less explicitly, continued into Skylarking and Oranges and Lemons. Some of Blur’s Britpop of the early 1990s (particularly 1993’s Modern Life Is Rubbish) mine a neo-psychedelic sound, and the Stone Roses’ dense, dreamy drive did as well. The Flaming Lips, after several idiosyncratic post-punk albums in the late 1980s, migrated to Warner Bros. as a neo-psychedelic band, culminating in The Soft Bulletin (1999) and Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots (2002). The Coral, Doves, Porcupine Tree and other bands have indulged in acid rock nostalgia here and there, emulating the vibe with varying degrees of success.

Before moving on, let’s credit the Church for originating the Australian fascination with neo-psychedelia. After a couple of new wave albums that favored pop and crystalline rock, they put it front and center on 1988’s Starfish, which has been cited by Treblezine as one of 10 Essential Neo-Psychedelia Albums. (“Reptile” on Starfish is a particularly outstanding example of the genre.) A recording of their 2014 live set at the Sydney Opera House is entitled A Psychedelic Symphony, drawing on their catalogue of 23 studio recordings up to that point. Finally inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame in 2010, some 30 years into their career, they are as much a foundation of Australian rock as Midnight Oil, INXS or AC/DC.

Where’s the acid?

If neo-psychedelia is not the second coming of acid rock, it is a vein of inspiration that has persisted now for about half a century. What, then is its claim? What makes “neo-psychedelia” psychedelic?

One tactic evokes the Beatles: the falsetto vocals of “Baby You’re a Rich Man,” the spacey organ on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” the churning, thick textures of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the Leslied guitar on “Sun King,” the phasing/drone combination that produces an air of mysticism in “Blue Jay Way” and (especially) the echo on many later Lennon efforts. Identifiable late-Beatles audio tropes are like a calling card for neo-psychedelia, an instant invocation of an era.

But neo-psychedelia also depends heavily on layers of synthesized sounds used in a way that was not common in rock songs before albums like Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here (1975), Alan Parsons’ I, Robot (1976) and David Bowie’s Low (1977), and the form seems almost inconceivable without them. The tendency towards complexity on all levels — rhythms, chord progressions, song forms, technique, sound layers — has more in common with mid-‘70s progressive rock than music of the acid rock era. Even the characteristically ethereal vocals of Tame Impala, which tend to float above the mix like some distant piece of Gregorian chant, bear more resemblance to a track like “Time” from Parsons’ 1980 album The Turn of a Friendly Card than to practically any actual acid rock recording. Compare the vocals on neo-psychedelic efforts with the full-throated Jack Bruce on “White Room,” Grace Slick wailing away on “White Rabbit” or Gary Brooker’s soul-soaked “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” and you hear how contemporary vocalists owe more to the self-effacing singing of millennial folk-rock than with early acid rock.

Tame Impala has become the form’s standard-bearer. “It Is Not Meant to Be,” the first song on InnerSpeaker (2010), evokes a late-Beatlish sound in a number of ways, none of them so obvious as to seem directly borrowed. The song begins with a repetitive motif of alternating notes similar to the opening bars of “Imagine,” “Strawberry Fields” or “I Am the Walrus.” The sound then broadens into a phase-shifted wash that evokes (again) “Strawberry Fields” or “Tomorrow Never Knows.” The other main ingredient is Parker’s vocals, recalling Lennon’s falsetto in “Baby You’re a Rich Man” or perhaps Prince. The voice and the production as a whole are pretty close to “#9 Dream” on Walls and Bridges, a particularly psychedelic post-Beatles track. Doubling down on the Lennon sound, he adds echo, recognizable from the title track of Magical Mystery Tour and other late Beatles and Lennon cuts. Elsewhere on InnerSpeaker, “Alter Ego” replicates not just the electronic background sound but the percussive effects and inside-out drum beat of “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

On subsequent Tame Impala albums, the vocals are about the same, and echo effects and phase shifters are still in play, but Lonerism (2012) emphasizes synthesizers and simple keyboard ideas, just as suggestive of Yes’s Tales of Topographic Oceans as anything by the Beatles. Currents (2015) adds harmonies and, like The Slow Rush (2020), veers in the direction of rock, pop and even dance music without losing the aesthetic elements of “neo-psychedelia.”

For all that, Tame Impala still sounds like a typical millennial act. Beatle-like gestures are a kind of haze that surrounds the music without owning it. Parker’s first album was mixed by Dave Fridmann, producer of the Flaming Lips, MGMT, Spoon and other groups. It’s hard to hear a big gap between the sound of Tame Impala and Animal Collective’s Merriweather Post Pavilion (2009).

Although some acid rock bands began to experiment with synthesizers after the Monkees used one in 1967, they did not become a primary means of expression. Neo-psychedelic bands, however, have leaned heavily on polyphonic synthesizers and other synthesized effects. That might make them seem more like neo-prog bands, and some of them sometimes are; “neo-psychedelic” avoids the stigma of prog-rock that would turn people off while drawing a line back to the early days of rock. But none of these bands are wallowing in ancient billabongs; they are making contemporary tracks on a landscape that has been trodden by bands of every era.

Parker is a former member of Pond, and he has produced, co-produced and/or engineered most of their albums. Members of Pond are in Tame Impala’s touring company, so they are practically two faces of the same band. For all that, they do not share much in the way of sound. On Pond’s early albums, they rock heavy, emphasizing guitars and thick synths. “If Tame Impala is Perth’s Beatles, then Pond is the city’s Rolling Stones,” opined one reviewer. Musically, though, Pond has more in common with early Floyd or Nektar. With The Weather (2017), they waxed lighter. On Tasmania (2019), they veer towards a form of 1980s synth-pop in the realm of Human League, New Order, the Cure and a-ha, with echoes of the Church and others. Their most recent, 9 (2021), remains in the psych-pop mode. For an introduction, Man It Feels Like Space Again (2015) is as solid a neo-psychedelic set as any.

Five Bands in Search of an Era

In the title track of their 2014 album Psychedelic Resurrection, the Blues Magoos mainly seem to be promoting their return after 46 years. Had they boldly claimed that a lot of rock bands hopping in the Wayback Machine would be the next big thing, they would not have been far off. That’s certainly happening in Australia, and — if we drop the idea that anyone can really turn back the clock — it’s easy to see that today’s neo-psych bands have plenty to offer on their own terms.

To the extent that the current Australian penchant for psychedelia constitutes a nostalgia for the glory days of rock, one might seek explanations in malaise about the present: the COVID pandemic, raging wildfires, the refugee crisis. There does seem to be a good deal of dysphoria to go around, but chronology does not support any of these psycho-social explanations. King Gizzard has been in the business since 2010, Hiatus first appeared in 2011, Rolling Blackouts CF was founded in 2013 and the Crumpets in 2014. Tame Impala and Pond have been at it since 2007 and 2008, respectively. That lets COVID, nativism and the climate off the hook. Which leaves the success of Tame Impala. As one of the most prominent Australian musical exports since Men at Work (if not Midnight Oil), Kevin Parker is surely as responsible any other factor for the surge Down Under. But five bands riding a renewed wave of interest in psychedelia approach it from very different musical directions.

Shedding and Shredding:

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard formed and met while studying music at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology; virtually all of the members are multi-instrumentalists, so much so that when drummer Eric Moore departed in 2020 he was not replaced. The band debuted in 2011 with Willoughby’s Beach, a “9 track garage rock EP” firmly in the post-punk mold and free of any psychedelic influence. Without entirely ditching punk, 12 Bar Bruise (2012) veers more toward metal and grunge, with standard guitar solos here and there, and uses more basic rock progressions than their later work.

Eyes Like the Sky (2013), a narrative modeled on spaghetti westerns, was written and spoken by Broderick Smith of the Dingoes, with a score performed by KGLW. Murder of the Universe, a 2017 concept album, is likewise an audiobook. Both seem to owe a little to the Moody Blues, but spoken lyrics with an art-rock backdrop is a versatile genre that has attracted artists as diverse as Frank Zappa, Gil Scott-Heron and Patti Smith. The enjoyment of such projects is contingent on stories that may be profound or puerile, poetic or pointless: King Gizzard offer a bit of each.

KGLW moved into neo-psychedelia with Float Along — Fill Your Lungs (2013) and Oddments (2014), both of which reproduce the feel of acid rock as it was. The first cut on Float Along, “Head On/Pill,” goes on for 16 minutes. The title track makes musical reference to the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows,” whose first line is “Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream.” Sound effects (a warped, scratchy record) and studio vérité (coughing) stoke the vintage ambiance; the tracks are filled with organ solos, heavy reverb, period-appropriate pedal effects, blues harmonica, sitar-like drones and (a rarity on neo-psychedelic records) finger-picked acoustic guitars. Much of the singing harks back to garage bands, perhaps a little too much so: acid rock had its share of tone-deaf scratchy vocals, but for every nasal whiner there was a John Lennon or Grace Slick. On I’m in Your Mind Fuzz, another 2014 release, the first four tracks and “Am I in Heaven” zip along to a rapid beat, while the diversity elsewhere on the album invokes the past without acknowledging any particular style.

Quarters! (2015), which has a total running time of exactly 40:40, contains four songs. Guess how long each one is? (Beginnings and endings were fudged to fit the timings.) Amid the prog-rock sound, “God Is in the Rhythm” employs the classic ‘50s chord progression (C – A minor – F – G) familiar from “Teenager in Love” and many other songs from the era. The acoustic Paper Mâché Dream Balloon (also 2015) returns to a ‘60s feel, but without neo-psychedelic effects. It’s more melodic than many of the band’s other records, with abstract lyrics that incongruously paint images of blood, bone, carrion, cadavers and vampires. In “Trapdoor,” the lines “Everybody knows what’s under the door / And everybody goes to great lengths, for sure / To hide themselves away and keep the beast at bay” only hint at the album’s unsettling outlook.

KGLW took it relatively easy in 2016, releasing only Nonagon Infinity, an accessible prog-metal album in 7/4 time. It won an Australian ARIA award for Best Hard Rock or Heavy Metal Album and got glowing reviews in Pitchfork and elsewhere. Where a lot of neo-psych records lack obvious sincerity, the band seems determined to make a statement here, and it shows in the drive, originality and even accessibility in a way that had not really been in evidence since Willoughby’s Beach. The similar Infest the Rats’ Nest (2019) occasionally resembles King Crimson (if not Dream Theater) but demands a particularly high tolerance for space-fiction and the prog-metal sound palette.

The start of 2017’s cavalcade, Flying Microtonal Banana — like the paired K.G. (2020) and L.W. (2021) — is heavily invested in Eastern harmonic scales and microtonal tunings, some of it realized with custom-made instruments, including guitars with added frets. The degree to which the use of microtones alters the sound differs from album to album, but these fascinating and unusual efforts reward repeated listening, with few noticeable ties to psychedelia and a lot to progressive rock. “If Not Now, When?” on L.W. is one of my favorite KGLW cuts; the whole album, quarter tones and all, is one of their best, incorporating elements of prog, jazz rock and heavy metal in a dense but approachable mix. Notably, the simple 12-note theme of the first track on K.G. is used again on the last track of L.W., suggesting some kind of closure.

Sketches of Brunswick East (2017) is something else again: though it still drinks from the microtonal fountain, it’s largely a jazz rock set with Eastern tunings and what sounds like primitive tape flanging. (Rae Lland of the pot site Leafly calls it one of “five modern psychedelic rock albums to listen to while high,” citing records by Primus and Animal Collective as well.) Like a jazz trio (with prominent use of a celesta) backing soul-tinged vocals, the album is nothing like any of the jazz-rock styles of the late ‘60s or early ‘70s (Soft Machine, If, Laura Nyro, BS&T, Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell, etc.) and bears at most a passing resemblance to Marvin Gaye or Curtis Mayfield. The title references Miles Davis, who earned his psychedelic jazz cred with Bitches Brew. It’s a collaboration with Alex Brettin, whose albums as Mild High Club also offer a jazz-based, synthesized soft-rock sound which can be heard as a latter-day version of psychedelic pop.

Polygondwonaland (2017), a prog-rock set with little of the demonic prog-metal, stresses rhythmic changes (not polyrhythms) and boasts some great tracks, like the opening “Crumbling Castle” and “Horology.” Lyrically, the album offers multiple stories: a kind of history of the continental breakup that morphs into the story of a ruler or god, and then to the acquisition of tetrachromacy (the ability to detect light waves beyond standard RGB vision). Typically vague statements from lyricist Stu Mackenzie suggest they are all related, and indeed that everything KGLW has ever done is somehow related, but that really boils down to the view that whatever he thinks up is related to whatever else he thinks up. As a marketing ploy, it keeps Gizz fans looking for clues to the allegedly unfolding grand design.

Gumboot Soup, the last of their five 2017 releases (including Murder of the Universe), consists of songs that didn’t fit any of the previous four themed works. Mackenzie says that it contains “some of my favorite songs of the year.” (Mine too.) It seems like a more concerted effort at songwriting as opposed to concept album production, and if it is in some respects an entry in the neo-psych catalogue, it is also the album that least wears that on its sleeve. (Though the sleeve does owe a debt to R. Crumb’s “Keep on Truckin…”) Those not up for great experimental challenges may well find this one easy to appreciate. Fishing for Fishies (2019) is an enjoyable hard-driving blues-rock record that falls in with the up-tempo sounds of George Thorogood and the Black Keys.

For modern neo-psychedelia in the Tame Impala vein, Butterfly 3000 (2021) has Parker-like ethereal, airborne vocals (is the bridge in “Shanghai” a Bee Gees tribute?) and synthesizers, plus acoustic guitars and standard rock instrumentation. The songs run into one another, many using a pentatonic scale that calls to mind Chinese music. (There’s a remix version titled Butterfly 3001.) After that, KGLW released the Satanic Slumber Party EP, a three-part dystopian theater piece with spoken word, heavy metal, art-rock and electronica components made in collaboration with Tropical Fuck Storm. (The song “Garage Liddiard” on 12 Bar Bruise was obviously a reference to the man who was at that time the leader of the Drones, so the relationship goes back a ways.) They followed that with Made in Timeland (2022).

Having diligently listened to each of their 19 full-length studio releases (not to mention two officially released live albums) multiple times, I’ve paid enough dues to offer some conclusions about this massive creative endeavor:

1. To their credit, King Gizzard is capable of seamlessly pulling off frequent switches of genre like the mask-changing performers at the Chengdu Opera — or, I suppose, like Lizard Wizards. Credit extraordinary instrumental proficiency and an apparently endless supply of musical ideas and influences. Although only part of their output can be considered strictly neo-psychedelic, the neo-something feeling snakes through much of their extensive repertory.

2. It is a fine thing to be inspired by great music of the past, but there are risks as well. One is that songwriting can become gimmicky rather than sincere, and on some of these albums it feels a bit like affectionate, tongue-in-cheek mockery — not unlike the soundtrack to the film A Mighty Wind, which lovingly teased 1960s folk. Also, KGLW’s 1960s retro efforts lack good hooks, both vocal and instrumental. There are exceptions, like “Pop in My Step” on Float Along — Fill Your Lungs and “Sense” (Paper Mâché Dream Balloon), but on albums that should use catchy songwriting to ground the rear-view-mirror aesthetic what you get instead are reminders of style and form.

3. Working in prog- and art-rock relieves the band of such obligations, and they tend to shine with instrumental virtuosity, studio technique and pure creative energy. Few rock bands still do instrumentals, but they are scattered throughout here. Given the complexity of the band’s musical ambitions, there is plenty of reason to take these as seriously as the songs with lyrics.

4. What are the lyrics actually about? The early albums are full of unease, but the source is unclear: ecology? culture? gender? romantic loss? personal psychology? I read a lot of their early lyrics as peevish cousins of their musical dumpster diving. More recent records concern ecological, political, moral and psychological issues tucked into stream-of-consciousness musings, rarely landing on a definite point of view. Mackenzie is clearly concerned with environmentalism and what human beings are doing to the planet; Infest the Rat’s Nest could almost be a protest album. But what he’s on about in Polygondwonaland is anyone’s guess. Gumboot Soup touches on environmentalism, but Butterfly 3000 is for the most part allusive discontent and escapism. Lyrics that vaguely allude to fantastic or dystopian features of the world are nothing new (cf. Bob Dylan, Robert Hunter, Pete Sinfield, some late Beatles) but there is a thin line between linguistic playfulness and pretentious pseudo-poetry.

5. The natural rhythms of KGLW’s lyrics do not consistently fit the music. So accents often fall on the wrong syllables and lines are broken to match the meter. This is not unusual in rock, but here it happens too often; a great songwriter rethinks a line rather than stretching it to fit.

6. Some of the unfolding story Mackenzie claims to be following is about a cyborg character; fans refer to this fictional world as the Gizzverse. Such multi-album links have been done before, for example, by 10cc, who concocted a loose story based on air travel and telecommunications; and cosmological fantasies based on eco/techno fears were thematized on some of Nektar’s albums. But those comparisons may also constitute a kind of warning sign: 10cc, in spite of their genius and their hits, never quite lived down the quip that they were “too clever by half,” and for all Nektar’s musical brilliance their fantasy worlds didn’t grab large audiences outside hardcore prog lovers. Mackenzie might want to consider putting a cap on the Gizzverse at some point. Writing more directly about emotions and experiences might help lure people to KGLW’s extraordinary musical talents.

Howling at the Moog: Hiatus Kaiyote

To understand Hiatus Kaiyoke in context, we need to start with the beginnings of psychedelic soul by Sly Stone and the Chambers Brothers (or maybe Sun Ra), a genre furthered by the Temptations, P-Funk and Stevie Wonder’s mid-‘70s trilogy (Innervisions, Fulfillingness’ First Finale and Songs in the Key of Life). The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998) is a later touchstone; Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe are among those who have brought it up to date. This is quite a potpourri of styles, and if anything holds it together it is the impulse to pepper soul music with elements grabbed from rock, jazz and fusion, not to mention film and show music. Neo-soul, though, which involves gospel-influenced vocals and jazz-infused music, is often traced to Aaliyah, D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar (1995) and (again) Lauryn Hill. Other proponents of the genre include Macy Gray, Mary J. Blige, Meshell Ndegeocello and Maxwell.

Hiatus Kaiyote draws some inspiration from Wonder’s early ‘70s albums, with a sound not dissimilar to acid jazzers Jamiroquai (minus the strong dance beat). HK was up for a Best Progressive R&B Album Grammy (won by Lucky Daye’s Table for Two) in 2021. The four white Australians do soul with enough conviction to spawn online comments along the lines of “I can’t believe they’re not Black.”

Tawk Tomahawk, the band’s 2013 debut, includes the catchy “Nakamarra,” which received a Grammy nomination for Best R&B Performance in 2014. Singer Nai Palm sings like Aaliyah and Badu, while the band’s keyboard-driven sound moves in the direction of psychedelic soul classics like Shuggie Otis’s Inspiration Information or Andre Lewis’s early 1970s band Maxayn. Tracks like “Lace Skull” take an even bolder, experimental approach akin to Björk’s Volta.

In 2015, the 18-song Choose Your Weapon (with the band’s comments on 15 of those cuts available online) eschewed pop-soul for a unique, more complex sound. Constant changes of beat (and some actual polyrhythms), a vocal style so free and melismatic that it defies sing-alongs and a thick palette of keyboards and synths contribute to a challenging but immediately appealing blend. Imagine Aaliyah or Badu backed by Chick Corea and Return to Forever, or Spyro Gyra with prominent lead vocals. All four band members are credited with playing keyboards; Palm and Paul Bender double up on guitar; numerous percussionists contributed. Palm says that “By Fire” (an album standout, alongside “Breathing Underwater”) and “Borderline With My Atoms” are two parts of a story involving an arrowhead she found in a Sydney shop and eventually brought to the Navajo man in Arizona who made it; the story had both personal resonance and philosophical import for her. “Molasses,” a low-key breakup song, and “Building a Ladder,” the closer, are also notable.

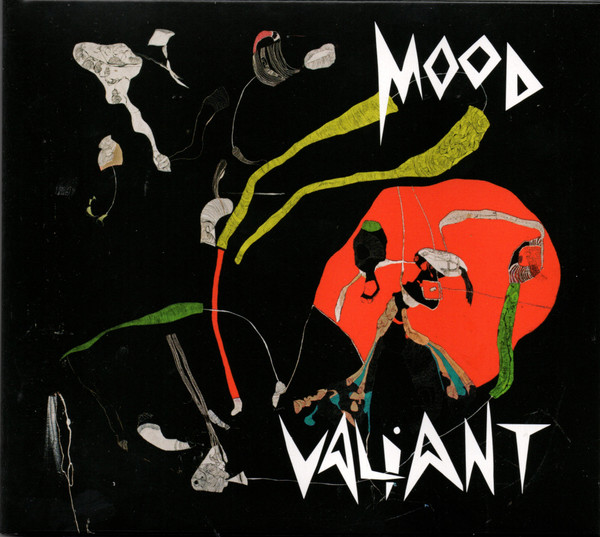

Mood Valiant (2021) is an about-face for HK. Not quite abandoning experimentation, it’s nearly a basic soul album with a taste of familiar string and horn arrangements, courtesy of Brazilian composer/producer Arthur Verocai, who is also credited as a performer on “Get Sun.” Though far from the scintillating Choose Your Weapon, the album does have the complex and attractive “Chivalry Is Not Dead,” “Rose Water” (which rocks along in 5/4 time) and “Blood and Marrow,” a slow, moody closer with a catchy melodic line. With lyrical economy, “All the Words We Don’t Say” is not a timely commentary on self-censorship, but (paradoxically?) a setting of those words alone; “Red Room,” which focuses on a childhood room of Palm’s that glowed red at sunset, repeats the same brief lyric throughout the song. Two tracks under a minute each have little or no lyrical content. Palm was fighting breast cancer when she wrote many of the lyrics; the instrumentals were recorded before her diagnosis. The album title may also have to do with her illness: she relates that her mother, who died of the same disease when Nai was 11, owned black and white Valiant station wagons and drove whichever car suited her mood. I love a good quip, but to call the album a “valiant effort” would be underselling it, though it’s a step back from the excitement of their previous release. (Any qualms about the record’s nomination for a Progressive R&B Grammy have to be considered in light of Justin Bieber being up for a Best R&B Performance prize.)

In any case, the recent single “Canopic Jar” finds the band again feeling adventurous, so presumably the next album will reflect that. Aside from their group efforts, Palm’s 2017 solo album Needle Paw is well worth a listen. For one thing, it demonstrates her considerable abilities on guitar more clearly than the group recordings. It also offers a more personal interpretation of many HK songs. The album includes soulful versions of Jimi Hendrix’s “Have You Ever Been (To Electric Ladyland)” and the title cut from Bowie’s Blackstar. These are beautiful, reflective renditions, and the whole disc is a testament to what she has been able to accomplish in spite of personal and emotional challenges.

Doling Out Jangles:

Rolling Blackouts CF

The Rolling Blackouts CF’s music can be traced back to Roger McGuinn and the chiming 12-string Rickenbacker he played in the Byrds: a trebly guitar playing a lot of single notes with frequent string crossings produces a sustained ring (a sound oddly dubbed “jangle” by rock critics). Anything that reminds us of Byrds songs like “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Eight Miles High” links directly to music made for altered states of consciousness. In Australia, the Brisbane band the Go-Betweens are the closest reference point, and RBCF acknowledge a debt to them.

A local factor beyond the jangly guitars is the Melbourne scene called “dolewave,” often to the chagrin of bands so identified: the Twerps, Dick Diver and the Drones. If none of them ring a bell, here’s one that might: Courtney Barnett. Her style, occasionally though not insistently jangly, is – by her own description – the result of immersion in this dolewave culture, which embraces a raw guitar sound, eschewing most distortion and effects boards (not to mention precise tuning), with minimal use of synthesizers. (Guitarist Tom Russo of RBCF uses chorus pedals among his basic effects, but that’s about it. For a deeper dive into his influences and musical milieu, see this interview.)

Dolewave started about a dozen years ago; for characteristic examples, try “Good Advice” or “Someone’s Changed” on The Twerps (2009); “Dreamin,” “Who Are You” and “Anything New” on Twerps (2011); the title track of Dick Diver’s New Start Again (2011) or “Alice” and “Water Damage” on Calendar Days (2013). Then compare those to “Sick Bug” or “Fountain of Good Fortune” on RBCF’s The French Press, or to “Cameo” on Sideways to New Italy. If you haven’t already had that sounds-like-Courtney-Barnett moment, check out “Rae Street” on her Things Take Time, Take Time (2021). The guitar sound, production qualities and song style are all similar, but what really joins all these tracks is a manner of vocal articulation, and the lyrics behind them: “doleful” would be a fair word for it, but perhaps a better way of saying it is that the songs typically express anxiety, irritation or depression at the daily assaults of modern life and relationships. As protests they are personal and sometimes dramatically understated, but the underlying attitude seems to be one of frustration at the indignities one has to endure just to get along in the world.

Dolewave is no stylistic straitjacket, and Barnett explores many musical avenues without entirely leaving the scene behind. So “Avant Gardener” on The Double EP: A Sea of Split Pea (2013) keeps the basic beat and vocal style of dolewave with spacier (psychedelic!) production. To hear how naturally this can be merged with jangle pop, check out “Write a List of Things to Look Forward To” on These Things Take Time… Although it’s the most jangly thing she has recorded, the open sound of dolewave guitars is a cousin of the jangle sound, which is why it sits so easily on top of the Go-Betweens’ influence to define the sound of RBCF.

RBCF has cut a median path to popularity with a sound that is at once reminiscent of the Melbourne scene and pepped up with more twangy picking and catchy guitar riffs. Dolewave vocals are often droned or chanted or barely sung, but that sort of thing surfaces only intermittently on RBCF albums. They sound a bit like Midnight Oil, a band that is generally a lot heavier, but tracks on Blue Sky Mining (“Stars of Warburton,” “Forgotten Years,” “King of the Mountain,” “River Runs Red”) and Diesel and Dust (“Put Down That Weapon,” “Gunbarrel Highway”) make prominent use of the jangly, cross-picked guitar. RBCF’s vocals sometimes echo those of Midnight Oil frontman Peter Garrett, and in tracks like “Fountain of Good Fortune” (from The French Press) and “Mainland” (on Hope Downs) they similarly engage with issues of class and ethnic privilege. (Russo clearly follows multicultural voices in the U.S., giving shoutouts to Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ocean Vuong, Kendrick Lamar and others.)

The seven songs on Talk Tight (2016) maintain a closer connection to the stripped-down Melbourne sound than RBCF’s later efforts — but they also announce an intention to move beyond it with strong instrumental hooks. A catchy guitar line makes “Heard You’re Moving” the standout cut here. The title track of the six-song French Press (2017) is by far their most streamed track: a bitter conversation between two brothers whose double entendre use of an unstable phone connection (“Are you moving out of range?…I’m having trouble making you out…I think I’m cutting out”) connects it to the Giles Field/Courtney Barnett song “I can’t hear you, we’re breaking up” (2014). In “Julie’s Place” and “Colours Run,” the lyrics leave a lot to the imagination.

RBCF’s first full-length recording was Hope Downs (2018), their best work to date. It starts off with the hard-driving pop of “An Air-Conditioned Man” and “Talking Straight” and continues with “Bellarine,” the album’s most inspired item. The lyrics allude to disillusionment, personal struggles and romance, but the fog of words can be difficult to penetrate; it’s dissonant to hear lyrics delivered with great sincerity and feeling but no clear indication what they’re about.

Sideways to New Italy (2020), is titled for a town up the coast from Melbourne, a center for Italian-Australian heritage, perhaps a point of reference for the band’s two Russo brothers. “Falling Thunder” and “Beautiful Steven” move toward a more obviously neo-psychedelic sound; the former has a striking chorus. The recent single “The Way It Shatters” / “Tidal River,” which preceded the new Endless Rooms album, finds RBCF in a power-pop mood, a bit more Midnight Oil than dolewave.

On the recently released Endless Rooms, RBCF adopts a harder sound, banging out chords more vigorously and leaning into guitar leads with acid rock’s piercing tone. Confirming their ability to craft a catchy tune, songs like “The Way It Shatters” and “Blue Eyed Lake” also wax edgier than earlier efforts. There are new touches, like fade-out guitar solos and spoken word cuts, that push the boundaries of jangle rock, and the album as a whole tilts more in the direction of Midnight Oil than dolewave. Titles like “Endless Rooms” (“Through endless rooms we walk / Just trying to find somewhere to lay down”), “Open Up Your Window” (“Open up your window and let the air rush in”) and “Bounce Off the Bottom” express pandemic angst and the desire to return from isolation to a normal life.

Tea and Cake:

The Psychedelic Porn Crumpets

Names being unreliable indicators of style, the Psychedelic Porn Crumpets have a foot and a couple of toes in progressive rock, particularly King Crimson and what, in the critical fashion of these times, should be called “neo-progressive” — including prog-metal bands like Dream Theater and the more “neo-psych” Porcupine Tree. (Critics use the term “progressive” for these bands; my own preference, for everything since about 1977, would be “quasi-progressive.” “Pseudo-progressive” would also suit me fine, but that’s a whole ‘nother essay.) PPC has a penchant for bursts of synthesizer atmospherics amid a typical guitar-heavy sound. However, song lengths have diminished since the first album, and a recent four-song EP leans more towards neo-psychedelia.

Songwriter Jack McEwan mentions eLed Zeppelin and Crosby, Stills and Nash as influences; guitarist Luke Parish cites Dave Gilmour, but anyone looking for either songwriting or guitar playing that resembles any of those had best look elsewhere. McEwan also mentions the Mars Volta, a more apt comparison, at least for PPC’s earlier stuff. As with that group, I find a lot of PPC’s pyrotechnical sauce out of proportion to the musical nutrition. When they curtail the most aggressive instrumental impulses, however, immersive sonic landscapes remain.

“Cornflake,” the first track on PPC’s first album, High Visceral (Part One) (2016), starts out with the whole band playing a sinewy Fripp-like line in unison but then washes into a mysterious atmosphere akin to Klaatu. The title cut is an instrumental with bird songs at the beginning. “Found God in a Tomato” recalls Nektar, with sections that could have been left off 1975’s Remember the Future; even the title would have suited that band. The long last cut is heavy on synthesizers and mostly instrumental.

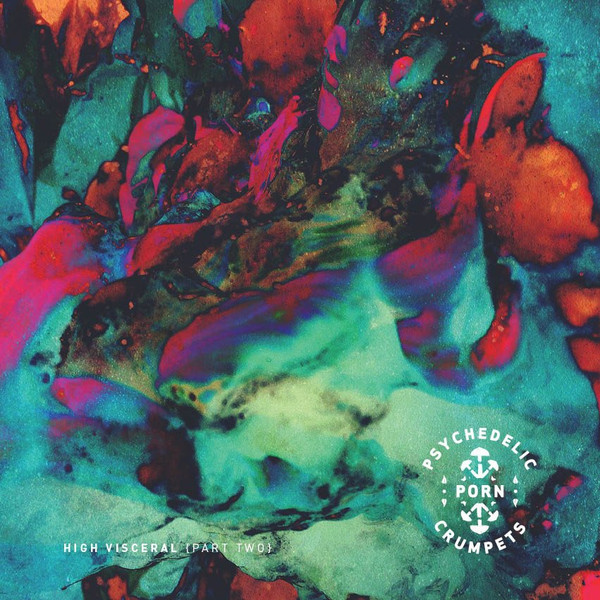

High Visceral (Part Two) (2017) is more or less the delayed second half of a double album. Three of the first four tracks (“Nek,” “Gurzle” and “Ergophobia”) would make perfectly fine entries on a prog-metal playlist, while others explore the mellower side of prog/neo-psych. The dreamy “Coffee” enters the realm of a certain kind of acid rock on the back of Tame Impala, who often explore similar sonorities. So does the middle of the next cut, “Dependent on Mary,” while the outer parts are a nod towards early hard rock.

And Now for the Whatchamacallit (2019) is perhaps PPC’s most concentrated effort at writing proper lyrics and melodies to accompany their instrumentals. Don’t miss the eye-catching psychedelic artwork by McEwan (who is also a graphic designer). He’s said the album is about escapism in various forms, but most of the lyrics are inscrutable. “Keen for Kick Ons” at least intermittently refers to a late night of debauchery (roughly the meaning of “kick on”). “Bill’s Mandolin” is about, er, something escapist, I guess:

Carnival’s rolled up, now get your coffee pots on high

Children of the festival are waiting for your song

Antivax the tesseracts then consultate your smile

Architect the cause of my division in a conscious country mile

Then I ascend off again carrying Bill’s mandolin…

“Hymn for a Droid” is followed by a brief piece of synth drawl. All of this is well within prog territory, but perhaps earlier and more approachable prog than some of PPC’s other work. “Native Tongue” is quieter and atmospheric. “Social Candy,” another of the singles, includes what I assume is an intentional musical reference to “Baby, You’re a Rich Man.” In “My Friend’s a Liquid,” the rising guitar line that introduces each verse struck me as familiar, and I went searching high and low, finally hitting on “What in the World” from 25 O’Clock, the first Dukes of Stratosphear LP. The verses begin with the same five-note sequence, but I suspect it’s a coincidence. “When in Rome” sounds like late King Crimson. After the instrumental “Digital Hunger” the album ends with “Dezi’s Adventure,” a quieter cut that has at least one foot in psychedelia.

“Tally-Ho,” one of the more effective cuts on SHYGA! The Sunlight Mound (2021), sounds a hundred times closer to Yes than it does to classic acid rock, but then Yes was the most psychedelic of the early prog ensembles. The investment in a rapid and heavy instrumental sound pays off, but the similar “Mr. Prism” isn’t as effective. The whole album is pure prog, with heavy synths on “More Glitter” and “Round the Corner” and the rest guitar-driven in a style roughly comparable to King Crimson in the ‘80s. The final cut (“The Tale of Gurney Gridman”) ventures into mellower territory.

On Bob Holiday (2022), the title cut is again in PPC’s neo-prog style, but “Bubblegum Infinity” (the title cut of an earlier three-song version of the collection) points more towards psychedelia (and, at some points, towards Green Day). So does the largely acoustic number “Dread & Butter,” while “Lava Lamp Pisco” is a bit of a hybrid. (Pisco is a brandy made in Peru and Chile; I suppose one can induce some interesting hallucinations by consuming enough of it in the presence of a lava lamp.)

Like KGLW, PPC are technically impressive, lyrically elusive and musically challenging. But they also resemble their elder peers in sometimes channeling their boundless creativity into very appealing songs.

Music for Pleasure:

Tropical Fuck Storm

“Psychedelic” would not be the first word that comes to mind to describe Tropical Fuck Storm’s music, which is not to say you can’t find moments in the history of acid rock (for instance, in the work of Can and Hawkwind) that match their art-rock style. On the other hand, there is occasionally something quite approachable in their irreverent songwriting, almost as if the efforts at weirdness (which they acknowledge) are too halfhearted to completely undermine the catchiness of a particular melodic or rhythmic motif. That is not to say that the music overall is an easy listen: frequent changes of ambiance, half-sung and half-intoned lyrics, interludes of noise and atonality and other elements that break the rock mold combine to create a challenge that would likely keep TFS permanently off the pop charts were they not occasionally ready to indulge in more accessible tunes. Those who prefer groups that mix it up and keep life interesting may enjoy them; those who prefer songs they can sing along to may not, at least for the most part.

Each song on the last album by the Drones, Feelin Kinda Free (2016), began with ambient noise before moving into song form, albeit with atypical instrumentation. By contrast, on the first TFS album, A Laughing Death in Meatspace (2017), the band plays freer with song formats, technique and backing tracks. (“We didn’t want to do a regular rock and roll rhythm section” says multi-instrumentalist Erica Dunn). The opening cut, “You Let My Tyres Down,” has the bones of a standard rock song, maybe even a hit, but as it goes on, heavy guitar distortion does away with all hope of unvarnished popular appeal. The next song, “Antimatter Animals,” goes even further, with a guitar line that skirts atonality and lays down plenty of feedback, along with growled lead vocals and loose harmonies that sound like a first rehearsal. Things go on in this manner throughout the album, with most cuts having aspects of some standard song format only to be taken in a different direction by distortion, noise, jagged guitar lines and vocals that vary from sung to chanted to shouted. There are Zappaesque moments to the music, while the vocals sometimes conjure up Modest Mouse or the Decemberists; lyrics, politically engaged with an anti-establishment tenor, are mostly delivered as points in a heated argument. “Shellfish Toxin” is an instrumental that begins as an essay in atmospherics and builds to a threatening climax before petering out. The female counterpoint to Liddiard’s rough lead vocals (e.g., in the title cut and “Rubber Bullies”) is an effective element.

Braindrops, which dropped in 2019, makes even less pretense at accessibility than the first album; it starts with “Paradise,” six minutes of noise, with lyrics offered in what might diplomatically be called passionate protest. The title cut follows the band’s playbook of a modest beginning that builds to an explosive climax before waning, as does the final cut, “Maria 63.” Things calm down with “Who’s My Eugene,” nicely sung by Erica, while “The Happiest Guy Around” shows respect for Talking Heads and demonstrates TFS’s ability to produce music that could find a wide audience.

Their latest album is Deep States (2021). It includes a rap song, “G.A.F.F.” (Give-A-Fuck Fatigue); and “Blue Beam Baby,” which features a lot of parallel harmonies. The band calls “Suburbiopia” (another Fiona vocal) “an epic exploration of the upside of being in a suicide cult”: “They’re probably wrong but maybe they were right,” is their appraisal (but Shining Path were rather a homicide cult)… “Don’t knock nothing until you try it.” It’s hard to tell how serious they are. “New Romeo Agent” again feints in the direction of popularity; sung by Erica, it bows toward Suzanne Vega. Gareth himself has cited the next song, “Legal Ghost,” as a concentrated songwriting effort. Released initially as a single, the music is accessible, but the lyrics concern the suicide of a former girlfriend. The obvious pain and emptiness the song expresses makes for a jarring contrast with the treatment of the subject in “Suburbiopia.”

The band brushes the outer fringes of neo-psychedelia mainly by virtue of their avant-garde techniques. If there is one album from the 1960’s that captures the spirit of TFS it is Captain Beefheart’s 1969 art-rock masterpiece, Trout Mask Replica. It may not be psychedelic, but it’s a trip, and so is Tropical Fuck Storm.

Final Thoughts

Success on a global scale has not yet found most of these bands: other than Tame Impala and the Go-Betweens, a Ranker.com list of “The Best Australian Bands, Ranked” includes Tame Impala at number-36 and King Gizzard at number-59. The other bands discussed here don’t even make the Top 200. Australian rock culture does not always fit smoothly through the filters of European and North American tastes; the predictable veneration of AC/DC, Midnight Oil and Men at Work fades smoothly into love affairs with bands like Cold Chisel (2), perhaps Oceania’s answer to the Grateful Dead or Phish, and INXS (3). The Bee Gees check in at number-24, the low rank perhaps reflecting their tenuous claim on being an Australian band at all.

International audiences don’t always pick up on another nation’s musical choices, however strong their output may be. Kate Bush, for example, is a musical icon in England, with multiple chart-topping singles and albums and a ton of critical respect; but her music doesn’t really sell in the U.S. (While Bush recently fell short of the votes needed to be elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Pat Benatar, who covered “Wuthering Heights” on her second album, did get in.) Speaking when the Church was inducted into the ARIA Hall of Fame, mainman Steve Kilbey lamented the gap between the quality of Australian popular music and its international recognition. KGLW, already an institution in Australia to the point of running an annual Gizzfest, regularly make the independent albums charts in Billboard but their singles don’t chart, and their shelf of awards is strictly from Down Under. Perhaps fortunes are about to change for these bands. With Tame Impala’s last two albums going Top 5 in the U.S. and Britain (number-one in Australia), Hiatus Kaiyote’s Grammy nominations and King Gizzard’s major concert draws, there is obviously an international market for neo-psychedelia in one form or another. To find out if Australia’s latest musical export is poised for real international recognition and commercial success, stay tuned, feed your head, and by all means burn the midnight oil.