By Dave Schulps

Ready for a 46-year-old Q&A with a band you may never have heard of? Well, this being Trouser Press, we hope that at least a few of you are familiar with Stackridge, or may become curious enough to stream or buy one or more of their five 1970s albums: Stackridge, Friendliness, The Man in the Bowler Hat, Extravaganza and Mr. Mick (the first four of which were released in the U.S., though The Man in the Bowler Hat was altered and retitled Pinafore Days). Or their 1999 reunion (of a sort) album Something for the Weekend; the 2001 setting-the-record-straight The Original Mr. Mick; the 2009 more-of-a-real-reunion album, A Victory for Common Sense; a rash of live albums culminating in The Final Bow (2017); and this year’s 50, a 51-cut three-disc set celebrating the band’s 50th anniversary.

Formed in 1969 in the southwest of England as Stackridge Lemon, the band mainly hailed from Bristol and Bath. After losing the Lemon and signing with MCA, they became known for high-spirited and often comical live shows — including the dustbin lid percussion that became a signature — and offbeat songs about elephants (in common with Syd Barrett, but few others), penguins, comic book creatures, female explorers, galloping gauchos, indifferent hedgehogs, dangerous bacon, giant onions and more.

While they toured the U.K. heavily through 1975 and had some chart success there, they did very few shows in Europe and none in the U.S. other than a 2011 performance of “The Last Plimsoll” on The Late Late Show With Craig Ferguson. (The Scot was evidently a fan, and the band had reunited.)

On October 1st, 1975, I spoke to co-founder Andy Davis (Andy Cresswell-Davis, actually) and Mick “Mutter” Slater, who had joined the band shortly after its inception. I believe the interview took place at Rocket Records’ offices in London. The next day, I got to see them play for the first time, at King’s College. With drummer Peter Van Hooke making his debut and the recently added Dave Lawson of Greenslade on keyboards and synths, the show proved quite a bit proggier than I’d expected, even sounding a bit like King Crimson at times. The audience was quite unlike the ones in St. Albans that Mutter describes in the interview. It was a good show, but not the wild, comical romp I’d expected.

The interview for Trouser Press, then its second year of existence and still a small-circulation fanzine, was never published because we kept expecting that the album they were recording at the time (Mr. Mick) would get a U.S. release from Rocket. So we waited…and waited. The album came out in Britain and — after Rocket tinkered with it (hence the 2001 release, The Original Mr. Mick) — flopped. The group broke up soon after, and the interview was packed away.

A few years later, Davis and the band’s other singer-guitarist, James Warren, turned up as the Korgis, scoring a Top 20 U.S. hit with “Everybody’s Got to Learn Sometime.” (When Stackridge re-formed in 2007, they made the lone Korgis hit part of their live set in the U.K.) Nonetheless, like Stackridge, the Korgis never did a U.S. show.

I recently came upon the interview in a long-forgotten box of cassettes. With this being the band’s 50th anniversary year and all, we present the great lost Stackridge interview in the hope that they become, to paraphrase Howlin’ Pelle of the Hives, “your new favorite old band.”

Can you tell me how Stackridge got together?

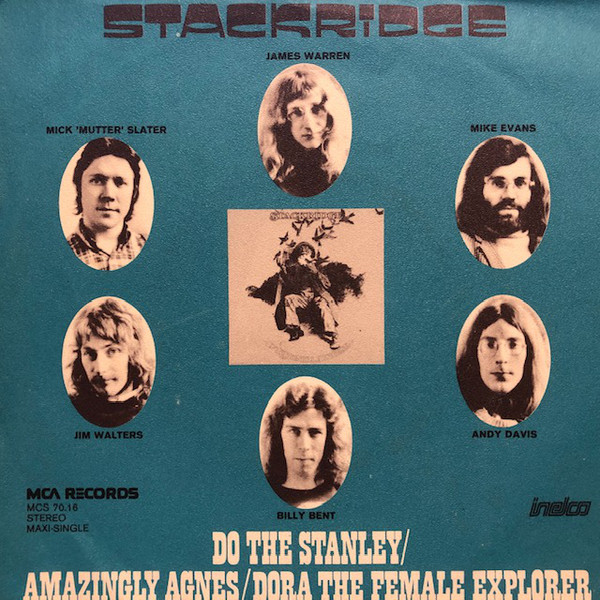

Mutter: The original Stackridge was formed in the winter of 1969 in Bristol. The founding members were Andy Davis [guitar, keyboards], James “Crun” Walter [bass] and a drummer called Bill Bent, plus other appendages. The first recording lineup jelled in the autumn of 1970, which was the three names I’ve mentioned plus Mike Evans [violin, cello], James Warren [guitar] and myself [flute, vocals].

Andy: I knew Crun from a previous group that we were in, Grytpype Thynne. Actually, I met Crun first of all because we wanted another guitar player in the band, and a good friend of mine had a band in a place called Bath, which was about 12 miles away. And I got them a gig at a club in Bristol so that I could steal the lead guitar player behind his back. I asked Crun to join and he joined. It was in that group, actually, that Crun wrote a couple of songs for that group and we thought, “Ooh, that’s fun, that’s more fun than playing this rubbish.”

What kind of “rubbish” were you playing?

Andy: Well. It was blues, not that that’s rubbish, but the way we played it was pretty awful. So I persuaded Crun that the best thing to do would be to psych everybody else and try and form a new group with more interesting instruments, wind or violins or whatever. We didn’t actually know what the lineup was going to be, we just started looking around.

Were you writing then?

Andy: Crun was, yes. And about six months after that, we sort of arrived with a fairly stable lineup and we all started doing it then. And it was a sort of measure of success.

And how did you get your first recording contract?

Andy: A friend of ours from Bristol who ran a club said, “Let me be your manager, lads.” So we said, “That sounds like a good idea,” because he was planning to move to London. We moved to London and various people came to see us and we took no notice of them whatsoever, and it turned out that one of them was there from the MCA, and then he liked us and offered us a contract.

What kind of music were you doing then? The same type of stuff that’s on your first album?

Andy: No, not really. That was where we made our biggest mistake, really, and we’ve been making it ever since. We played on stage totally differently than we play on that LP, and we thought, “Well, when we make our first LP, we’ll have to put more interesting stuff on it,” and it got a bit out of control really, so wasn’t a true representation.

Have you always played different things on stage than your albums?

Andy: No, not so much since, but I think we were wrong in assuming that the stuff we were doing before we started recording wasn’t interesting enough to listen to on an album, because I think it would have been. And it was different in that it was sort of slightly… Oh, I don’t know. It was just different.

Did you have any original philosophy or intention behind the band?

Andy: No. I didn’t have any philosophy for the group as a whole. I had some of my own, well, not really philosophies, but I always wanted to write songs like John Lennon or Paul McCartney and wanted to play the guitar as well as Eric Clapton. The usual ones. Around about the first six months, I suppose, we all started thinking in terms of entertainment as well, we liked the idea of entertaining as opposed to just standing on stage and playing. And we all had fairly unique senses of humor really.

Yeah, which comes across on all the albums.

Andy: The fact that humor did come out in a big way was a bit of an accident really, because of a tour we did in Denmark. We were always hard pushed to fill out an hour in England, and when we got there we had to play for about two and a half, I think, without any warning at all, so we just reeled off a few jigs and learnt a few silly things, “Twist and Shout” and other things. And, of course, Mutter had to talk for twice as long, and we managed to get through it, and when we came back to England we sort of kept all of it in there.

Did any of you have musical training of a classical nature or any kind… or are you all self-taught?

Andy: Neither of us did. Keith [Gemmell, ex-Audience sax player and clarinetist, who joined in time to play on Extravaganza] had musical training, but none of the rest of us.

Did you have singles released from the first album? Did you ever try to establish yourself as a singles band?

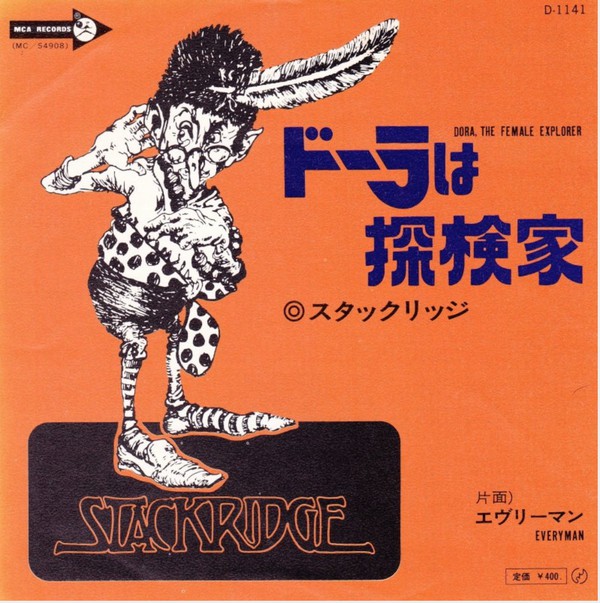

Andy: There was a single on the Stackridge album, “Dora, the Female Explorer.” And that was about the only single we’ve ever written. Actually, that came surprisingly close, so people say. Since then, it’s not that we’re not interested in singles, but we find it difficult to write singles. We don’t even try to write singles, but it’s something I don’t think I’m naturally good at, but I would very much like to have a successful single.

Where do you get subject matter for your songs? Does it… just pop up?

Andy: I think it just comes from people’s imaginations, really. Especially Crun. Most of the imagination is Crun’s, really, in those sort of titles. It comes from his sort of not wanting to be ordinary, or always wanting to do something outrageous, so he writes very imaginative lyrics about elephants and things. But one of the nice things about the next LP is the imagination’s matured a bit. He’s not writing songs about elephants anymore, he’s writing about more everyday sort of things, which I’m much happier about.

How about “Slark?” Was that sort of a comic book type of character? I remember something from the liner notes about it being a monster.

Andy: Yeah. It was never absolutely clear to me what type of monster it was, because again it was Crun who thought about it. I don’t think he’d thought of it in terms of being a monster as such, it was just sort of some horrible, great, indescribable thing. Not exactly anything in particular.

Did you ever have any intention, or was there any effort made, to really break the band in the U.S.? All the albums [to this point] have come out in America.

Andy: No, we’ve never… We’ve had several tours lined up, but they’ve never got any further than, “We’re going to the States in July or September or whenever,” and by the time that comes it goes back another four months.

Why do you think that is?

Andy: I really haven’t got a clue, to be honest. I can’t understand it really, but actually I’m quite pleased we haven’t been yet, because…

Just because you’ve got the act now to the point where…

Andy: Yeah, I’ll think we’ll be that much better when we actually do get there. And I hope we go within the next six months.

What was the live act like around the beginning? Did you have all the things with the garbage can lids and that type of thing?

Mutter: Well, the dustbin lids came in after about 18 months, I suppose, mid-’71.

And how did that get started?

Mutter: It constantly changed.

Andy: Yeah, it changed. It started off with not much happening at all and then Mutter started to announce things and stutter and make a bit of a fool of himself, he made people laugh, then when we came back from Denmark it sort of went on a bit from there, and then… Actually, because of the jigs we played to finish up the set, it left one person without anything to do really, because we didn’t need a piano on a jig, and I played the guitar, James was playing bass, so we thought, “Well, we…”

For the first couple of weeks Crun sat in the dressing room, which isn’t very good for an encore. So they said, “Let’s get him something to bang.” And I said, “Dustbin lids.” So that’s decided. After that, the humor changed a bit. When we dropped that, it became slightly more sophisticated, and Mutter started dressing up and being a little more suave and more the front man, whereas before there were three or four front men.

Where did you get the name “Mutter”?

Mutter: Oh, that’s a sobriquet from school days really. It’s just one of those that hung on really. I was always in groups, so I was usually called that.

Where do you get all these long words from?

Mutter: I read a lot last night before I went to bed.

I thought Friendliness was a little more what we’re talking about, again, maturing into a more humanistic and personal type of vision.

Andy: Yeah. Out of all of them, I think that’s my favorite as far as the material goes, but it was terribly produced. That’s more the type of material we like. I like all the material we’ve done, but some of it just didn’t turn out in the right way on record. It missed the point by a long way. Instead of hitting it right on the mark, it sort of drifted off so far that it ended up being sort of light entertainment rather than anything sort of… It’s difficult to describe, but it missed the point, anyway.

I thought a lot of the point came through on that album, even aside from the production. It was a very human type of album. You really get a good feeling from listening to it.

Andy: We got slightly possessed when we went into a studio then. We were so anxious to make a brilliant LP that we ended up… The quality was good on a couple of them, but the material suffered a great deal, and the feeling was totally lost. It was probably because we were never a natural performing group of musicians. There were always people playing things who played something else better, but had to play that instrument for some reason or other. And we’ve never ever had, strictly speaking, a lead guitar or a rhythm guitar or a piano player or anything like that, it’s always been hodgepodge, different people doing different things.

Do you switch off a lot on stage?

Andy: Only a little. We try to avoid that because it’s a bit boring for an audience.

Do you think the image of the funny stage act has hurt you critically? Have people tended to dismiss you as a joke band?

Mutter: It did, but only because there was too much of the humor. All the announcements were tongue-in-cheek, with the offbeat sense of humor that was innate in the group. Also, we slipped in, or we had, these comical songs as well. The more serious side of the group was only used as a relief from the comedy, really. Or apparently so. Whereas we used to prefer playing those, even though it is nice going down well.

Andy: But just about every reviewer has always said exactly that. In just about every review you get the comment, “Stackridge is supposed to be a fun band but there’s much more to them.” I think just about everyone has mentioned that.

What was going on at the time you and the drummer first left? Did the group come apart and then get back together, or was there always a Stackridge?

Andy: It was split up for about a day, I think, completely, because the tour of Denmark wasn’t particularly enjoyable. While we were over there, I had already talked several times about finding other people because it always frustrated me not having musicians that were expert on their instrument. All of us all played, or in that lineup everyone played, at least two instruments. Apart from Bill, the drummer, and he banged around on the piano. Everybody played at least two, and some of us played three or four. I think that’s a good thing generally, but I don’t think the band was particularly good musically, it never sounded that right to me. And so Mutter and I both started talking about leaving about the same time. When we came back, Mutter… No, it wasn’t Denmark, was it? It was later than that. Well, anyway, Mutter followed it through and said… No! No, that’s not… First of all we said we’d get a new drummer. Because that was the main problem.

Yeah. Was the Billy [Bent / Sparkle] on the first two albums the same person?

Mutter: Yeah.

Did he change his surname?

Mutter: Yeah. [According to an online source, Billy then became George Martin’s chauffeur.]

Andy: We wanted a new drummer. And we got one, but he was a bit hard to manage.

Mutter: Peculiar.

Andy: Yeah.

Who was that?

Andy: A bloke called John White. And he rehearsed for us and he did one television show, a live one, and after that he said he couldn’t do it, which meant we were stuck, really stuck. And that, for Mutter, was the last straw, he said, “Right, well, okay, I’m leaving.” And I said, “Yes,” and I was going to form a group with a guy called Gordon Haskell, who wrote “No One’s More Important Than the Earthworm.” And everybody sort of crowded ’round and tried to change everybody’s minds. Well, they changed mine, but they didn’t change Mutter’s.

I said at that time that the reason I was unhappy was that the music was missing the point. It was only a personal opinion, but I don’t like any of our albums at all. I listen to them and they make me feel quite ill inside, some of them. I think the material’s great, I mean it’s got so many possibilities, but it was always grossly overdone, to my mind. There was always too much material, and they were always trying to say too much. It was the studio disease.

If you took a certain amount of material, like “Galloping Gaucho” and a few of the other ones, and if we’d just played that on the piano, if I’d just played it on the piano and Mutter had sung it, that would have been just right for me. But the arrangement and the way it was produced, to me, has made it seem a bit sort of empty. A bit silly. And I don’t think it is silly, I think it’s a tremendous song and a great idea. And that goes for most of the material.

Whose idea was it for George Martin to produce The Man in the Bowler Hat?

Andy: Well, it was our idea, about seven years ago we thought, “Wouldn’t it be nice to do an album with George Martin?” But it wasn’t until we actually signed with Air that we started talking about it then, all practical with Martin and things, and everybody said, “Not a chance.” But it ended up, he did produce us.

But you were dissatisfied with it in the end. Did you feel it was his fault?

Andy: No, I don’t think it was his fault. I think… Funnily enough, I listened to it this morning. It must be the first time in about two years I’ve actually listened to it. And none of it was George’s fault at all. The things that annoyed me were the things that Mike [Evans] played on the violin, most of all, which made it really sort of… It was just the odd “doo doodle-oodle oodle” all over the place. And, a strange sort of contradiction, James [Warren]’s influence on my songs… My favorite song on the album is “Humiliation.” If James could do everything like he did “Humiliation,” it would have been lovely. If he’d done it with the same simplicity, it would have been great for me. But things like “Fundamentally Yours” just sound really empty. It was done too fast, I remember that at the time, overdone, things coming in and coming out. The only reason that was done like that was because we weren’t musically competent to do a simple, powerful backing track, and nobody’s voice was strong enough to really put a lot of conviction into it.

How about “Dangerous Bacon”?

Andy: Yeah, I like that. The end annoys me. Dan dan dan dan. Oh, and he went “dan, dan,” we cut it off.

Do you think the album turned out sounding too Beatle-ish also?

Andy: Some of it sounds very Beatle-ish, yes, especially the lyrics to “Dangerous Bacon.” It’s definitely the closest one. That’s why I’d like to hear Pinafore Days, and Mutter’s going to try and get it for me, because a couple of the tracks were changed ’round by Martin, and I might like that one better.

I don’t think it was too Beatle-ish, no. We needed somebody to come along and just tell us how to do it. We kept forgetting we were a group. I firmly believe that if we’d recorded it on my tape recorder, the quality would have been diabolical but the essence of it – the feel — would have been there. Because it wasn’t simple enough. It was all too much preoccupation with backgrounds and what we can do with a track and how many times we can double-track and things like that, and no thought at all for what we actually put down straight, first off.

Was that you putting that forward, how many things you can double track, or was that a general —

Andy: No, that was a general group feeling, actually. Because we had two people, James and Mike, whose specialty was overdoing things musically. Mutter stood back and let everybody get on with it really. Crun did very little. And I’m very easily persuaded about things anyway in the studio, because I like time to think about things. If somebody says, “Oh, let’s do that, and that would be nice there,” it gets a bit carried away, so…

Right after that album the personnel of the band changed…

Andy: Yes, that was the turning point really.

It’s funny because on the Pinafore Days album, the people who are credited are the people who came in afterwards and didn’t actually play on it.

Andy: We had nothing to do with [that] and didn’t know about [it] till it was too late. The usual situation.

They’ve started it off with “Spin ‘Round the Room.”

Andy: Yeah, and “To the Sun and Moon.” Bowler Hat side two is good. “Humiliation” is definitely my favorite track. But it’s the same with every album we’ve done really. If you’d taken off three, they would have been 100% better. It’s what they said about George Harrison’s double albums, they would have made a great single one. But the same goes for ours. It’s only a personal opinion, but if you’d taken “Fundamentally Yours” and “To the Sun and Moon” off that album, and if “Galloping Gaucho” had been done with more subtlety, and if “Road to Venezuela” hadn’t had that sick-making violin playing… I listen to it now, and it’s all going “doodle-oodle-oodle-oodle-oodle-oodle-oodle-oodle.”

The other thing that dictated what we did was the fact that we’d always been a working group, and you’ve got to play what you record to people.

Right. Yeah. You didn’t really…

Andy: If we hadn’t had worked so often, and if we hadn’t enjoyed it so much, if we were the type of people who would never get a stage act together at all, which it’s a pity we weren’t really, we’d probably have played very little, earned very little money, but when it came to making an album we would have… At the time when we did it, we said things like “Lummy Days” and “Galloping Gaucho” would sound much better with just piano or maybe a brass band and… but as it was we had to sort of group-ify them.

Yeah. Are you going to do that now on your new album? If something sounds good with the piano, are just going to do it or just…

Andy: No.

Are you still going to group-ify?

Andy: We’re not in that situation any more really, the stuff we’ve written is sort of different. And we’ve approached this one in a fairly sort of logical way really. So, I mean, there are a couple of very, very classical type of things on there, but… There’s a waltz, for instance, but it’s a subtle sort of reggae rhythm to it, which is nice. And there’s another slow, classical thing, about the speed of, I’d say, the “Moonlight Sonata.” It’s very 4/4, in line with it, but it’s got bass and drums on it, because it turns into a bit of a slow blues really. But that’s the way we’ve gone there.

Who are some of the people that are given composing credits, like Smegmakovitch and…

Andy: They’re all different people within the group.

Aah. And Wabadaw Sleeve?

Andy: Wabadaw Sleeve is the complete group, I think, isn’t it?

Mutter: Yeah, Wabadaw Sleeve is a pseudonym for the whole group, rather than just writing down Stackridge. Smegmakovitch was a lyric-writing team that was employed mostly on Pinafore Days, which was James Warren, Crun Walter and myself.

So it kind of was just sort of a joke?

Mutter: Well, yes, in that, because three of us had written so many of the lyrics on the LP, it would have seemed like a register of names after a line, say two people wrote the music and then another three wrote the lyrics.

Ah, right. What did you think of Extravaganza? Do you listen to that at all?

Mutter: Yes. I didn’t like it very much at all, to be quite honest.

Andy: No.

Mutter: On reflection, at the time I thought so. Quite depressing. Because it was something that, as far as I was concerned, any of the previous Stackridge incarnations couldn’t possibly have done. It would have been beyond our capabilities to play that. So it was that sort of thrill that…

Andy: I think it served a great purpose though, to the group anyway, to have gotten something like that out of our system. I think it’s a great improvement, but it’s a change in the make-up of the whole group really, because we’ve got people now who concentrate on simplicity to a great degree and see things in a much more clear-cut way, musically. Therefore, the band did turn out at being more direct and more easily listenable, and I’ve always been the type of person to think that… I like as little as possible on most things. I don’t like anything that isn’t 100% effective. That’s why I don’t like airy-fairy arrangements.

John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band LP is a bit of an extreme, but I think that’s where you ought to start, and go on a little bit from there. We do things naturally, our harmonies sort of come by accident. We wouldn’t spend hours thinking about putting harmonies on all over the place, because it doesn’t come naturally to us at all.

How has the band evolved since Mutter’s return? How did you get [new bassist] Paul Karas and who else did you work with?

Mutter: Rod Bowkett. During the spell that I was away from the group, there was an intermediary lineup that had some material that never actually got recorded, or never actually released. And then I thought, “Well, I’d like to go back and play again.”

What were you doing while you were away from the group?

Mutter: Well, I was forced to get an ordinary sort of job, just to get money, and I was having piano lessons. The main idea when I left was for me to have piano lessons and get enough qualifications to go to a college to study music… idealistically. As it turned out I couldn’t really apply myself to it, and I missed going out, being on stage and actually recording stuff that I had written, because it seemed a bit silly writing stuff and then just playing it to yourself. So I telephoned Andy and said, “Would you like to form a group?” And he said, “Yes,” and then he said, “Why?” And I said, “Oh, well, I’d like to join them.” So he said, “Alright.” And so we decided it would just be a good opportunity to get what we considered to be very good musicians for the rhythm section, because we considered one of the major downfalls of the group before was that we didn’t have a decent rhythm section.

And so numerous auditions for drummers and basses, and Paul Karas materialized with the auditions for a bass guitarist and vocalist, and Roy Morgan joined because he was a friend of Paul’s and Paul said, “I know a good drummer that I could get on well with and give you a good rhythm section.” That’s how those two came. And Rod Bowkett was someone that we’d known for quite a while. We heard some of the songs that he’d written and knew he could play the piano quite well, so that’s how we got him.

Yeah. And how did Keith [Gemmel] join the group?

Andy: He joined primarily as a replacement for Mutter when he left. And also as a replacement for Mike Evans on the violin, because we needed a lead instrument, didn’t we?

He had just finished with a group called Sammy, right?

Andy: Yeah, which he didn’t ever want mentioned.

All right.

Andy: We’d played together before, as Audience and Stackridge and things like that, and I think he liked the group anyway, and the idea of having the clarinet appealed to us very much.

And how did your rhythm section change recently?

Andy: We realized that it wasn’t right, the make-up of the group. So we sacked them. Mutter and I, and Crun are writing all the material, or choosing all the material, and just saying how it’s going to be done. It’s strange that when a new member comes into a band, or any one we’re in, we get overpowered without realizing it, musically. But I don’t think we’ll ever be successful until… Now Mutter and I are writing the material, and it’s sort of direct. It’s not simple material but it’s just-

Is Crun writing the material too?

Andy: Yeah, Crun’s a very good writer. It’s just not so silly and it’s more direct. And everywhere, it’s a bit freer. We’re not scared to sort of play things a few times and make noises or sound effects or… It’s freakier as well, if you’ll pardon the expression.

How about the Gordon Haskell song? How did you decide to use that on Extravaganza?

Andy: Gordon was a person we met about three years ago. He made one solo album called, I think, It Is and It Isn’t, which has some lovely material on it, and we especially liked his lyrics, or some of them, and we just got a sort of admiration for him, in a very small way, we thought he was a nice bloke who wrote some nice songs. And then it came to a time when we thought about maybe doing material written by somebody else, and we looked around and thought, “That would be a nice song to do.”

Yeah. It seemed sort of strange on the album because it sounded so different than everything else. Did you like doing that kind of thing?

Andy: I did, yeah, at the time. But we can do things like that ourselves anyway now, you see. Now that we’ve got rid of all those sorts of bad influences, we would generally play something like that anyway. There was always a terrible phobia about playing things that were maybe too ordinary… There’s a fair amount of truth in that, I think, but you miss out on the fundamentals if you do that too much. We’ve written things that are simple and ordinary and never used them. Not that the stuff we’re doing now is simple and ordinary and boring, but we just let things happen naturally now.

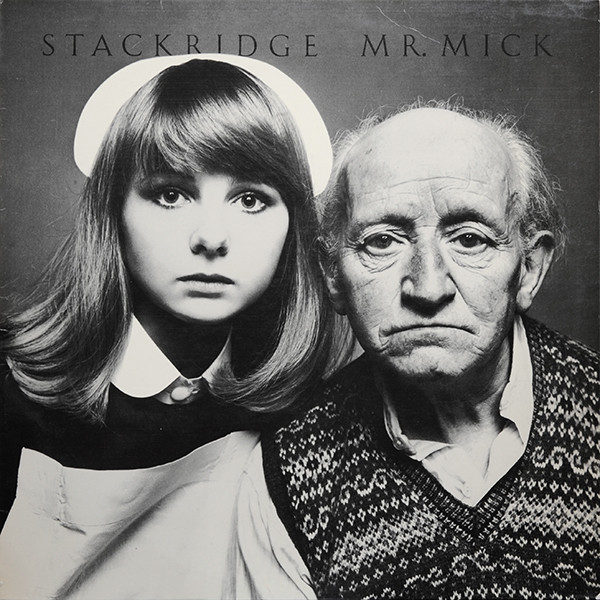

What’s the new album going to be called?

Andy: We don’t actually know.

Is it all recorded?

Mutter: It could quite possibly be called The Story of Mr. Mick, this version.

Andy: No, we haven’t decided what we’re calling it. Maybe Mr. Mick, because one side is going to be taken up with a story, you see, consisting of about five songs and a dialogue in between, which doesn’t sound very highfalutin, but nice.

Have you heard the American version of Extravaganza?

Andy: No. It has a different…

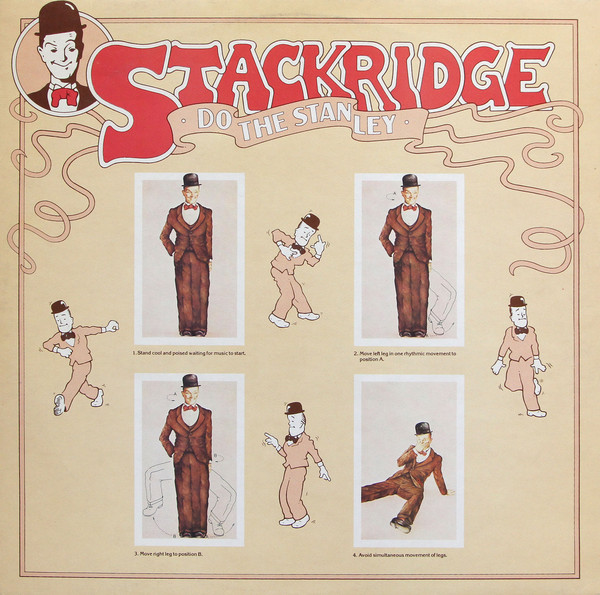

Yeah. Much different. And I think it works much better than the British album, because the instrumentals are juxtaposed so it doesn’t take up a whole side. There’s also a song in there, which I was going to ask you about, called “Do the Stanley.”

Andy: Is that on there? Really? Cor blimey!

That’s an old song, isn’t it?

Andy: Yes.

An old single or something?

Mutter: Yeah, it was a single that was done…

Andy: That was done just after The Man in the Bowler Hat, I think. Or was it just before?

Mutter: No, it was just before. It must have been.

Was that a dance craze you were trying to start?

Mutter: It was, in a very obviously tongue-in-cheek way. It was just one of those conversations you have in the van going to a booking, you were sort of thinking back to the days in 1960 and “The Twist.” You’d think, “We used to do the Shake and the Twist, there used to be dances coming out every week.” You thought, “There don’t seem to be any these days.” It was just one of those fleeting conversations, and I was thinking about it, and I came out with this tune on the train. I got back and played it on the piano, and I thought, “Ah, yes, that could be a dance.” And I thought, “Right, what can I do now for the name of a dance?” I thought, “I’ll just call it a human name,” and, lo and behold, “Do the Stanley.”

In fact, in terms of a mild philosophical sense, the dance, what I used to do to it, is just make an idiot of myself, and that’s all I wanted to do really, is just get people up and make idiots of yourselves, which I think is a nice thing to do. Not all the time, but it frees a few inhibitions. But it got out of hand, unfortunately.

Yeah. I’m sorry that this had to be before I got a chance to see you on stage. I’m going to see you tomorrow, but… Because I’ve heard so much about the stage part, and then I can’t really ask any questions about it.

Andy: You’d need to see us about once a year to follow the way we change. The stage act now, we haven’t really got as much emphasis on it as we did at the beginning. Mainly because of finance, but there are other reasons, too.

Are you going to maybe push a little more to come to America, now that you think the stage act is more together?

Andy: Yes.

Mutter: Unfortunately we don’t have that much say. Not the actual group itself, because obviously all of the flights have to be booked, I suppose.

Have any of you ever been there?

Andy: Keith’s been. And our drummer. Both our drummers.

After we’ve done the album, if it turns out well, then I think… I’ve been waiting to have a really good record to promote, because [it would be a] waste of time otherwise. So if we get that, then I suppose I’ll move hell and everything to get over there. Because I think that’s where we’ll be successful, if we’re ever, even.

Okay. I think you would really do well over there, I think it’s… Bands with a good stage show just seem to go down well.

Andy: Once we’ve got this set, this stage act, sort of developed a little bit more… It could be the best stage act we’ve ever done, when it’s sort of done, especially with “The Story of Mr. Mick” in it. For a number of reasons, we’re only a five-piece at the moment, which isn’t really that workable. So when the time comes and we go to the States, we’ll want at least one more person, maybe two, and rehearse it well. But it’s a more of a uniform set, it’s easier for everybody to like it, I think. It’s not too silly and it’s not too serious. It’ll be just about right.

Who’s your rhythm section right now?

Andy: Well, Crun is the bass player, and our actual drummer is Peter Van Hooke. We like to think of him that way anyway, although we haven’t played with him yet.

We needed a drummer at very short notice, and he came down and rehearsed and liked the groove and said, “Yes.” He’s taken the job on a sort of session basis, but he couldn’t make the first three gigs, so we got a stand-in for the first two and then found out the stand-in couldn’t do the other one. So, so far this week, we’ve done three gigs and two different drummers, and tomorrow’s a different one, so the lineup’s changed three times in a week.

We’ve got a stand-in, John Halsey (ex-Patto a.k.a Barrington Womble/ Wom of the Rutles), but Peter Van Hooke’s our first choice and the one we’ve done the album with. It’s chaotic, quite frankly, at the moment. When things are under way better it should be far more fun, but he’s a very, very fun drummer. He’s just what we’ve been looking for in a drummer, he really is. He’s very Ringo Starr-ish, but with a lot of flair, technique.

Does John Halsey do anything in the stage show?

Andy: No, because he’s not permanent, which is a great shame, because he’s got a fantastic sense of humor. In fact, in other bands he’s been in, like Grimms, he did a stand-up comedy routine. But you never know. We like a nice thick sound, so when the lineup becomes more permanent, and if we ever go to the States, we’ll probably have about seven, instead of five, which would be another keyboard player and possibly an extra percussionist. If we have that, John would be ideal, as he could also do his comedy thing and everything.

Who’s playing keyboards on stage now?

Andy: I am. And Mutter. We’re both very basic pianists, but-

Effective.

Andy: Yeah, that’s the point, we find we do it better than any other pianist we’ve tried out. We might make more mistakes, but when we actually play, we seem to play it more effectively. It’s not going to be a permanent arrangement.

So who is this Mr. Mick?

Mutter: Mr. Mick? Well, he’s the hero of the story, obviously, Mr. Mick and the Dump. And he’s an old age pensioner who still, like all old people really, have got their own mind and their own wounds, and he’s very fed up being shoved away in a home on his own, and being treated as though he’s an imbecile. So, he, in a moment of frustration, just goes out for a walk, and he ends up at the dump. The tip. When he gets there, various things on the tip start speaking to him. And they have the same problems as him.

It’s a nice analogy really, sort of saying, “People, once they don’t want us, just chuck us here out the way. Don’t want us there, anything else to do with us.” And they sort of say, “Trouble is, we’re stuck with the same people all day because we can’t move about.” So, it’s a nice compromise at the end that Mr. Mick has this treat on Sundays of walking up to the dump and moving everything about so they can get to know each other. But it’s generally about the sadness of old age, really, or the sadness in the way that younger people treat older people.

To change the subject totally, what bands do you like now or in the past, other than the usual, I guess, the Beatles. Are there any?

Mutter: Very, very few. Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks I liked very much. Some work by Frank Zappa, not all. But apart from… I can’t think of any contemporary sort of rock groups at all.

Do you like the Kinks at all? I think I said it in the review, that there’s a certain parallel in my mind to the type of feeling for people that I get out of a lot of Stackridge’s material and a lot of The Kinks’ material.

Mutter: Quite honestly, I haven’t listened to anything of theirs for a long time. Some of Harry Nilsson’s things, Randy Newman’s, one or two of Don McLean’s songs. It’s mostly spasmodic material from various artists, rather than an artist or a group. Because obviously someone has different approaches and different tastes to you, so if they hit the mark with you one time, they probably diverge another time, and you think, “Oh dear, I didn’t like that at all,” or, “I can’t see anything…”

Do you have any places where you go down particularly well?

Andy: Well, St. Albans was one.

Mutter: Because you go down well, it’s not necessarily a good place to play. You play at St. Albans, they just go berserk. They’re just packed tight with all this seething mass of bowler hats. They’re just shouting and stamping all the time and shouting out for their favorites and you can’t hear yourself. They don’t really pay that much attention, so it’s not very enjoyable to play there. Especially once you go out there and they go berserk from the beginning, so you’ve got nothing to work for, really. You want to go out there and think, “Ah, right, got to win them over.”